Breaking the cycle

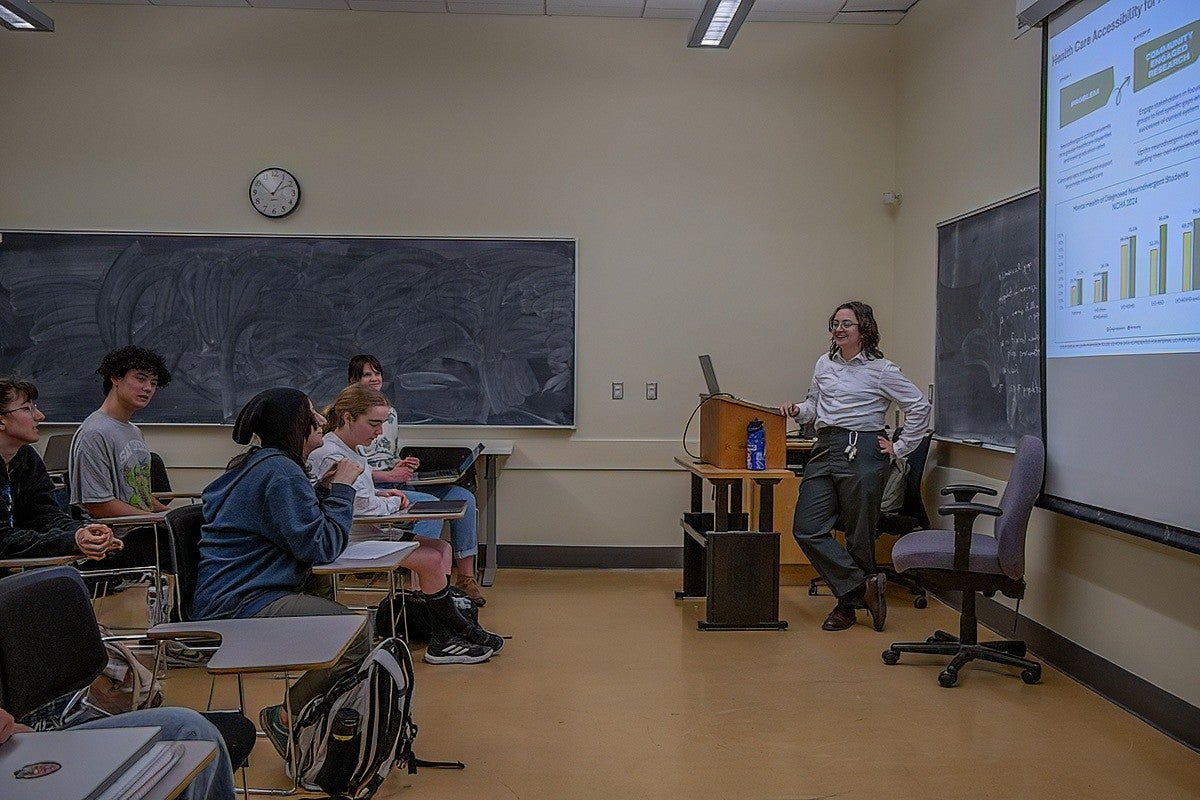

At an all-staff training presentation for University Health Services professionals, the audience of more than 150 applauded Aubrey Welburn for encouraging them to make services more accessible to autistic and otherwise neurodivergent college students.

The applause forced Welburn, who uses they/them pronouns, to plug their ears with their fingers. “Today, I’m wearing earplugs on my belt because it’s something I know I need,” Welburn had told them earlier in the presentation.

Welburn has always been a little different. In the small, southern Oregon town where they grew up, there weren’t many role models for a queer kid who might be on the autism spectrum.

As a young person, Welburn looked up to their pediatrician. In high school, they were more drawn to the medical field when recovering from major surgery. But the inspiration for their career path emerged from the research study they worked on at the University of Oregon as a Clark Honors College student.

While working on a positive parenting intervention under the guidance of Christina Karns, a researcher and associate teaching professor in the UO’s Department of Psychology, they regularly spoke with parents who were trying to make sense of their kids’ developmental differences. At the time, Welburn already knew they were autistic themselves. But they had always tried to hide their learning and social differences.

Suddenly, their identity became an asset. “I’m actually an autistic college student,” they told parents. Through their work on the study, they were able to provide families with support from their lived experience.

“I went from being very, I don't know, ashamed, or like, ‘we don't talk about the differences,’ to realizing that they're really important,” Welburn says. “If I would have had somebody like me growing up as a mentor, whether that be as a doctor or as some sort of support person, how I viewed myself would have been different.”

Aubrey Welburn

Major/minor: Neuroscience/Chemistry

Hometown: Central Point, OR

Coffee or tea: Both, at least a cup of each a day!

Song on repeat: Cheri Cheri Lady - Modern Talking

Thesis title: Health Care Accessibility for Autistic and Otherwise Neurodivergent College Students

Favorite experience from the HC: Either my HC 301, Top Conspiracy Theories, or working on my thesis

Advice for incoming first-years: Take advantage of the unique course offerings in the CHC to learn about things your major or discipline might not give you time for.

I’m grateful for: The support of faculty, friends, and family.

This summer, I can’t wait to: Spend time with friends and family and then explore Atlanta!

Next steps: This summer, I’m starting a two-year research fellowship in social neuroscience at the Marcus Autism Center, part of the Emory University School of Medicine. After that, I hope to matriculate into medical school.

Since coming to the Honors College and getting a formal autism diagnosis, Welburn has not only been able to be themself more freely but also embrace their neurodivergence.

After graduating with their neuroscience degree, Welburn will move to Atlanta to begin a two-year research fellowship at the Marcus Autism Center at Emory University’s School of Medicine, a leader in clinical research, testing and care for pediatric autism. The center’s focus on supporting – rather than “curing” autism – is what drew Welburn to apply and tout that they are autistic.

“That was a very hard match to be able to find,” they said of the fellowship. “I feel very fortunate that they want to support representation within the research and that their mission is more aligned with the actual autistic experience."

Being upfront and open about their autism is part of what has helped them pursue their goals, Welburn has come to realize.

Welburn’s autism went under the radar for much of their childhood in Central Point, Oregon. The oldest of eight children in a family they lovingly described as chaotic, they became a de facto role model and learned early on to function at a high level.

In grade school, Welburn was put into special education and assessed as dyslexic, along with having ADHD. They also came out as queer, which sometimes left them feeling discriminated against or invisible.

Welburn is the first person in their family to go to college and knew they would have to figure out how to pay for it if they wanted to study medicine. So, in high school, they worked their way to class valedictorian. Their efforts were rewarded with the UO’s PathwayOregon and Summit scholarships and others from the Ford Family Foundation and the Rennaissance Foundation, which completely covered the cost of attending the CHC.

The transition into college was challenging and overwhelming for Welburn. They found comfort in the CHC’s first-year Residential Community. It's where they met classmate Connor Lowery-North, who they later worked with as a resident assistant and still room with today.

“Viciously smart, almost intimidatingly so” is how Lowery-North describes their first impression of Welburn. After they penetrated Welburn’s cool demeanor, the two subsequently bonded “in the trenches” when both experienced breakups in their freshman year, Lowery-North says.

“They’re very empathetic,” says Lowery-North. "They’re very good at hearing something, being able to understand how that might feel for that person and being able to relate to them on a deeper level, which often makes people feel a lot more comfortable.”

Welburn says at the time they entered college, the world was still coming around to autism awareness and acceptance.

A supportive psychiatrist in high school recognized some traits of autism in Welburn, but they also displayed many strengths and coping skills. Despite their history in special education, Welburn was not formally diagnosed, and they didn’t enter college with the necessary academic and social supports in place to thrive, nor were they fully comfortable asking for what they needed.

“I recognized pretty quickly that I actually needed accommodations again,” recalls Welburn, who received assistive technology, additional time and quiet environments to complete assessments. “I was still succeeding, but it was taking me 110% of effort to succeed to the same degree.”

In order to get accommodations to take the MCAT, the test for medical school admission, Welburn needed a formal autism and/or dyslexia diagnosis. In January, they finally got “the paperwork that backs up the lived experience,” and life started to become more manageable.

The roommates had a little celebration, complete with a cake that read “Happy Autism,” says Lowery-North. “It was a fun time, being able to see something that they’ve been fighting for for such a long time finally coming to fruition.”

The change in Welburn's confidence and attitude has been transformative.

After witnessing Welburn’s push to get diagnosed, their mom and siblings have come to recognize some of the same traits in themselves and been motivated to seek their own diagnoses. Welburn is struck by the contrast in how their younger autistic siblings will experience coming of age.

“Being able to be diagnosed in elementary school or younger, for some of them, is this massive difference, and kind of breaking this cycle of not getting supports that are needed,” they said.

Welburn’s Honors College thesis project, “Health Care Accessibility for Autistic and Otherwise Neurodivergent College Students,” grew out of their experience navigating care on campus, as well as their involvement in the UO’s Student Health Advisory Committee at UHS and as the advocacy chair of the Neurodiversity Alliance at UO.

The project conducted two sets of focus groups: self-identified neurodivergent students at UO, who were asked about what healthcare accessibility has been like for them and ways it could be better; and University Health and Counseling Services clinicians, who were polled on recognized gaps in care and their comfortability treating neurodivergent students.

Welburn’s primary thesis advisor, Christina Karns, has been a key mentor for the project. Welburn needed help navigating UO’s Institutional Review Board process for conducting research on human subjects; they needed guidance on how to recruit and run a focus group; and how to analyze qualitative data.

"They just sucked it right up,” said Karns. “I would give some direction, and before I knew it, it would be done already.”

Karns watched Welburn balance their ambition with humility as the project grew to include additional researchers to analyze the mountains of data. Along with an intrinsic motivation to make a difference, a growth mentality and a can-do attitude were signatures of Welburn’s success, she says, and those bode well for their future career in health care.

Welburn presented the findings from both groups as a continuing medical education program for providers in UHS. Some of their recommendations are already being implemented.

One common barrier Welburn found is making the phone call to schedule an appointment. Online appointment scheduling was not available at UHS until Welburn’s research showed that it was a major gap. In April, the first student was able to use the new online scheduling system, thanks to Welburn’s work.

At Emory, Welburn will work on a trial for an autism screening tool for six- to nine-month-olds. During the fellowship, they plan to apply to medical school, likely at Emory.

Establishing early screening and providing support to families with autistic children are Welburn’s primary goals. “What will that mean,” they wonder, “if we can implement those type of supports for people in the same way we do for hearing and eye checks?”