Cracking the code

One of Maya Rios’s earliest memories is looking curiously at pictures in her mother’s old chemistry textbooks. A physicist, Maribel Rios worked as a managing editor at a biotech journal while raising her daughters.

Ever since listening to her mother explain physics and math theorems to her as a child, Rios has been seeking her own key to make sense of life. “I just was so fascinated that these formulas and numbers and patterns can explain how the world works, and I just wanted to know more,” Rios says now.

The Clark Honors College graduate eventually found that key in the field of data science, a broad set of computer-based skills and tools to make sense of disparate data points that reveal greater truths. It’s a growing major at the University of Oregon and its versatility has allowed Rios to tell the stories about the world she’s desperate to share and do so in a way that’s legible to anybody.

Whether she’s unlocking historical data and analyzing it to shed light on society today or synthesizing biological research findings to show what scientists are learning about tomorrow, Rios is now happiest when she can make a point using data science—and make it look good while she does.

Rios didn’t aim straight for data science as a major, though. Along the way to finding her groove, she’s found a technique for when nothing makes sense: Work hard and be nice to people, and things will all figure themselves out.

Maya Rios

Major/minor: Data Science major with an emphasis domain in Marketing analytics. Minors in English and Spanish.

Hometown: Eugene

Coffee or tea: Coffee, black with lots of sugar

Song on repeat: "Ciega, Sordomuda" by Shakira

Thesis title: Indigenous Data Visualization and Sovereignty of Carbon Sequestration in Marine Estuaries

Favorite experience from the HC: Attending the Women in Data Science Conference at Stanford in 2022

Advice for incoming first-years: It’s ok not to have everything figured out; just work hard and be nice to people.

I’m grateful for: Sunday dinners with my family.

This summer, I can’t wait for: Going to the coast with my friends.

Next steps: Work in the data science field for a few years and then pursue a master's degree in data science at UC-Berkeley.

Rios grew up in Eugene, the younger of two close-aged sisters. “Maya was always the one that just went for it,” says Maribel Rios. “A kid gets a toy, and half of them read the instructions, the other half just go for it.”

She had a new obsession every day, from the Guinness Book of World Records to the Olympics to space, and she loved to be right. “She would ask me questions that I had no idea what the answer was,” her mother recalls. “She was always into just knowing as much information about every little thing as possible. I’m really glad she found a specialty, a major that allows her to do that.”

The Rios family spent a lot of time hiking, camping and being outdoors – not by her dad’s choice, though. “I didn’t immigrate here to live in a tent,” he would joke to her mom.

Raised in farm-working families, both parents were first-generation high school and college graduates.

“Nobody knows the value of an education better than those that don’t have it,” Maribel Rios says, recalling her own parents’ insistence on her attaining her degrees. “We started saving up for college when our daughters were four months old.”

Maya Rios could never see herself moving far for college—in fact, today, she still lives in her childhood home. Sharing Sunday dinners and weekday breakfasts, the family is as close as ever.

“I do for her what my mother did for me, you know?” her mother explains. “‘I don’t understand what you’re doing, but here’s a snack, and here’s someone you can talk to or cry to whenever you want to.’”

A mentor at North Eugene High School turned Maya Rios on to the Honors College. CHC alum Gavin Bruce, Rios’s mock trial advisor at the high school, praised the faculty and curriculum so much that Rios decided she had to go. She was thrilled when she was offered admission, along with both the Presidential and Summit scholarships, which covered her tuition, fees, room and board.

When Rios entered UO in 2020 as a history major interested in law, the pandemic quickly showed her that nothing about her college experience was going to go as planned. “Nothing makes sense in the world,” she told herself at the time. “I’ll just do something that kind of maybe has some stability.”

She tried business but found that less than great for her: “Hated it.”

While she loved learning history, she says the practice of being a historian with its essays and research wasn’t for her, either.

She first heard of data science when polling coworkers on their majors at her campus job. Intrigued, she looked it up, and saw it had job growth and appealing salaries. She decided to take an intro class.

“It was difficult,” she recalls. “There was definitely a big learning curve, but I realized it was really great at getting to answers. It helped back up intuitive answers with data. It helped answer the sociological questions I always wanted to answer with history.”

Rios discovered that the process of building a data project was deeply satisfying. Translating old information into a new, universal language, like data visualizations or animations, let more people access the lessons in it, and just felt good to her.

As a tool, data science can be applied to a multitude of academic fields: accounting, biology, cultural analytics, earth science, geography, linguistics, music technology, physics and sociology are just a few of the concentrations the UO data science major offers.

Rios first came to appreciate the breadth of data science in 2023, while attending a Women in Data Science conference at Stanford University with three other female Honors College students and CHC Dean Carol Stabile.

“Maya likes to put herself in the way of opportunities that let her learn and grow,” Stabile says.

The conference broadened her horizons of what data science as a field encapsulated. “That’s when I started thinking of how I could apply data science skills to my original love of history and humanities,” Rios says now.

In particular, Rios loves the digital humanities arm of data science because it allows her to take a page out of history without having to comb through old books. Instead, “you take all these old sources and you build something in your computer.”

That could look like databases and online archives for a museum or library, with graphs, learning tabs and other user-friendly features – all increasing the accessibility of the information within.

But the conference also showed Rios the importance of the representation of women and minorities in the field, which by some estimates is only 15 percent and 3 percent, respectively. She went on to author an article with Stabile for Ms. Magazine, exposing the lack of diversity in the field and its impact on generative artificial intelligence.

Rios and Stabile argue that technology is partly a reflection of who creates it, and when the people training an AI chatbot are predominantly white males, the output is affected.

“There’s something called data deserts in AI – gaps in data. There’s less data available from women and especially women of color, so you have ChatGPT less able to spit out accurate information about them,” Rios says.

Along with that, a lack of female role models in the field makes it harder for young, female data scientists to see themselves succeeding.

With just a handful of women in her data science classes, Rios says that proving she belongs as a woman of color has been discouraging, exhausting, and lonely.

“You can’t be just average. You have to be great. You can’t just coast by. You can’t visibly struggle,” she says. “You have to know what you’re doing, at least externally, all of the time.”

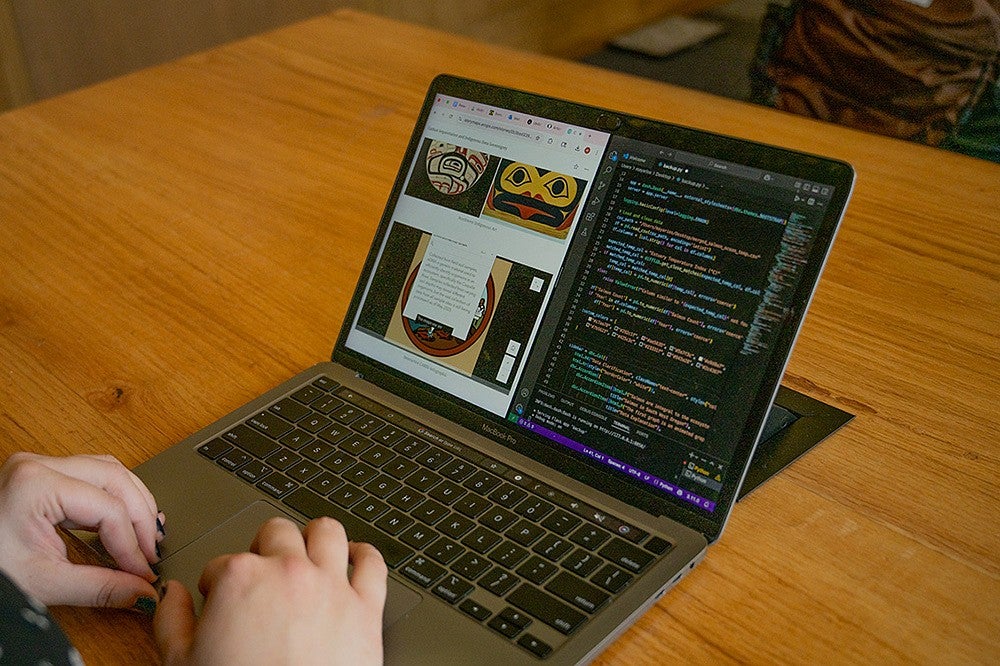

Rios’s thesis, “Indigenous Data Visualization and Sovereignty of Carbon Sequestration in Marine Estuaries,” uses research done by Ashley Cordes, an assistant professor of indigenous media in the environmental studies and data science programs at UO. Rios doesn't know biology and didn’t have to for the project. Rather, it highlighted Rios's expertise in visualizations.

“I feed the data through my computer, clean it, and put it through a Python script,” she says. A coding language, Python is what turns data into visuals. She found the packages in an online public library for data scientists called Matplotlib. They added color and dimension to the data plots and made them easier for the average viewer to read. Others can turn data into a GIF.

"Cheat codes” is how she explains how the codes modify the data.

“If you’re playing The Sims, or Mario Kart, you know how you type in cheat codes to get infinite life? That’s what they are,” she explains.

After Maya's code is applied, a viewer would see a set of attractive, nested graphs about carbon sequestration on tribal lands, all with a visual theme that references Indigenous art.

“It’s all this information that’s digestible to people who don’t know anything about biology, which is useful to me, because I also don’t,” she says.

Not knowing is something Rios has gotten a lot more comfortable with over the five years she’s been working toward her degree. Taking the extra year to find a discipline she truly matched with showed her that all you can do sometimes is keep working hard and being nice to people, and that in the end, things work out.

Rios isn’t letting adversity stop her. “I don’t want to brag, but I’m not too worried,” Rios says about finding work after graduation. She’ll hope to land a data analyst role at a nonprofit, perhaps working on a project similar to her thesis, before applying to a graduate program in data science at Berkeley.

“I still don’t know what’s going to happen next,” she says, “but now I’m a lot more sure of myself.”