Words matter

CHC classes: HC 101H Wait, What Do You Mean?; HC 277H Thesis Orientation; and HC 221H Poetry's AI

Hometown: West Linn, Ore.

Song on Repeat: The complete works of Beyoncé

What’s in the fridge: Sparkly water, fancy yogurt, every kind of cheese.

Guilty Pleasure: Reading a book all day long. Like, the entire day.

Favorite Movie: Casablanca

Coffee or Tea: Tea

Why I teach at the CHC: To work with students who are eager to navigate challenges.

If you take my class, you will: Learn to test ideas in community—not to arrive at a single right answer, but to practice the hard, necessary work of thinking for yourself. And you’ll probably read a poem or two.

I’m a stickler for: Ending class on time.

Books are everything to Lizzy LeRud, a new assistant teaching professor at the Clark Honors College.

She grew up in West Linn, Ore., and describes the house where she grew up as being walking distance to the town’s public library. One of their household principles was that reading deeply facilitates compassion, understanding, and a better connection to the world around us.

She remembers how her father, a pastor, would read from the Bible at the breakfast table every morning. “We came from a place where words – all of them – really matter,” LeRud recalls. “There were all kinds of books in the house. I always saw the words in books as being lovingly written by important people. They are meaningful.”

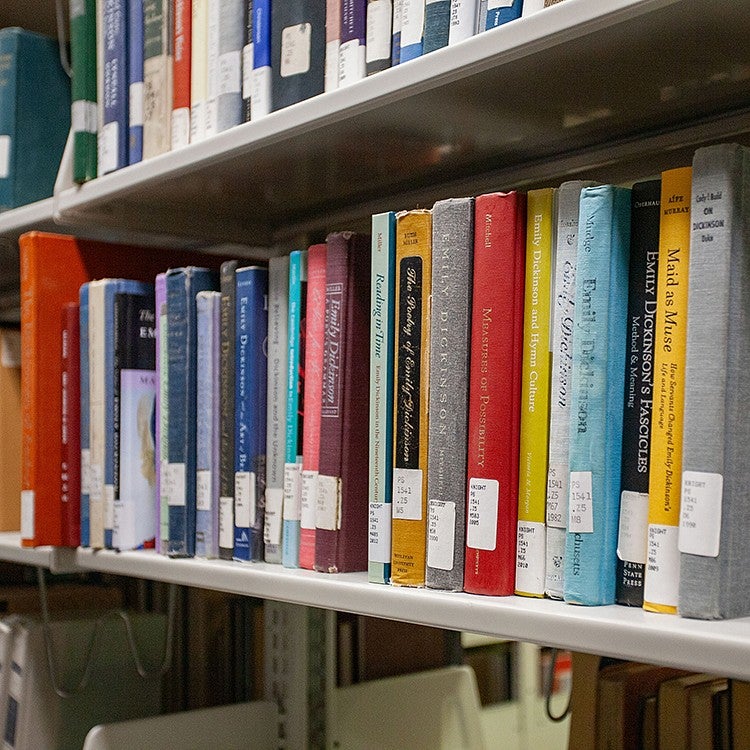

LeRud plans to bring that meaning to her CHC classes, where she will focus on poetry, poetics and American literature. She spent three years as an associate professor of literature and rhetoric at Minot State University in North Dakota. She also taught at Emory University as a NEH post-doctoral fellow in poetics and at the Georgia Institute of Technology as a Brittain Fellow.

No stranger to Oregon, LeRud spent six years in Eugene previously as a graduate teaching fellow and she received her PhD from the Department of English at UO.

She’s also at work editing an upcoming book called “Teaching Poetry Now,” which is forthcoming from SUNY Press. When it comes to teaching poems, “we’ve gotten a lot of things wrong,” LeRud says. “Traditional poetry pedagogy can be very alienating and elitist. This book is about centering students’ experiences. We’re honoring how poetry is for everybody—and that can change the world.”

As a teen, LeRud says she didn’t rebel against her parents. Instead, she latched on to poetry as an outlet. “I was a good kid,” she recalls. “I loved my parents.”

By the time she entered Westmont College, a private Christian liberal arts school in Montecito, Calif., she was eager to learn more about writing. She devoured poems by Frank O’Hara, Audre Lord, Gwendolyn Brooks and Allen Ginsberg, among others.

“I took this class in college on 20th century poets,” she remembers. “They were political advocates. They were activists. They were fighters for justice. They wrote not just to give us something beautiful but to confront what was out there that was wrong. It was inspiring.”

She decided to major in English and she also worked as a resident assistant for two years. “Watching my professors, I kind of thought theirs was the coolest job ever,” she says now. “You meet people making big choices about their future. You welcome them into longstanding intellectual debates. I had great professors who encouraged me and inspired me. I wanted to do that for others.”

After she graduated, LeRud took a roughly three-year break, working at different jobs. She was a legal assistant, and she also worked in marketing and communications for a while. But the academic world tugged on her and she headed to UO to begin her PhD studies.

Jeni Rinner was one of her classmates at UO and the two developed a close friendship. Rinner recalls being pregnant at the time while she was studying for her PhD. She describes LeRud as “the most wonderful supportive friend as I was navigating professional dreams and personal changes.”

Rinner calls LeRud “a creative thinker who gets the best out of everyone, full stop. I think she has a kind of revolutionary curiosity, from which her creativity grows. She meets good ideas and thinks about how to build on them, support them, expand them.”

Being back in Oregon is more than a homecoming for LeRud. It’s the place where she has always wanted to raise her own family. Her husband works in financial planning and they have a toddler named Thaddeus. She loves the Oregon Coast and she is excited to see her parents on a regular basis. “I definitely feel pretty lucky,” she says.

As she starts her first term as an official Honors College instructor, LeRud gets excited at her prospects. She wants students to see poetry as something creative, not as something pretentious and difficult. “Students should be prepared to test their opinions and change their minds in my classroom,” LeRud says.

She says she sees a lot of herself in her young students: they are highly motivated, they come from different backgrounds, and they are hungry to learn and succeed.

They are also creative and can think outside the academic “box” of grades and being at the top. “I like to see students find themselves in the characters of books and poems they read,” she says. “I want to get to know these students and see what I can offer them when it comes to their writing. With poetry, I often get to see them surprise themselves as they learn how cool poetry is. If you can teach it in a way where they embrace it, wonderful things can happen.”

She plans to have a variety of writing assignments for students, both as individuals and in groups. Collaboration and receiving feedback are keys to success for her. “We have all had bad experiences from working in groups and teams in the past,” she says. “What I try to do is to help us better navigate the hard stuff – and acknowledge how much we can learn from things going wrong. Even as we do our best to set up teams for success from the beginning.”