Confronting complexity

Major and minor: Multidisciplinary science major, chemistry, biology and global health minors

Coffee or tea: Both. I fell in love with coffee while living in the PNW but I still drink tea at least once a day. I like to still think of myself as a tea person.

Favorite experience at the CHC: Taking a course in the Prison Education Program with Professor Anita Chari.

Song on repeat: “Baby Steps” by Olivia Dean

Advice to incoming freshmen: Take a deep breath. You'll get there. I promise it's ok to take a break for a bit.

Thesis title: Factors Associated with Food Insecurity Among People Experiencing Homelessness

Favorite memory from childhood: Late night stuffed animal parties with my sisters when my parents thought we were sleeping.

What you will miss most at UO: My community. From friends to sorority sisters to colleagues to mentors, the community I’ve built here has truly changed my life.

What are you most excited for in grad school: Tackling a new adventure and finding a new community. While I know it’s going to be scary and uncomfortable, I am so excited to build something new and grow alongside incredible people

On many a cold day this winter, Bella Albiani is out on Eugene’s streets, giving out hand warmers, socks and hats. While most University of Oregon students are snug at home studying, preparing food or relaxing, she's collecting data at Bridges on Broadway, a housing facility serving one of the city’s most vulnerable populations: people experiencing chronic homelessness.

Being unhoused often goes hand-in-hand with food insecurity, a complex relationship Albiani is probing tirelessly for her Clark Honors College thesis. It’s an example of how Albiani doesn’t shy away from problems that seem impossible—she dives straight in. And she’s seen first-hand that change is possible.

Last spring, Albiani remembers parking her car underneath I-105 and walked into Eugene’s Washington Jefferson Park. Under bright blue tents, she met members of her research group, the Homeless Policy and Health Project, which was stationed there to engage the many unhoused residents of the park as participants.

Albiani greeted people, inviting them under the tents and introducing them to the study. She was met with a furry face – a German Shepard named Duchess, leashed to her friendly owner. Curious about their presence in the park, the owner approached and after talking with Albiani, decided he would participate.

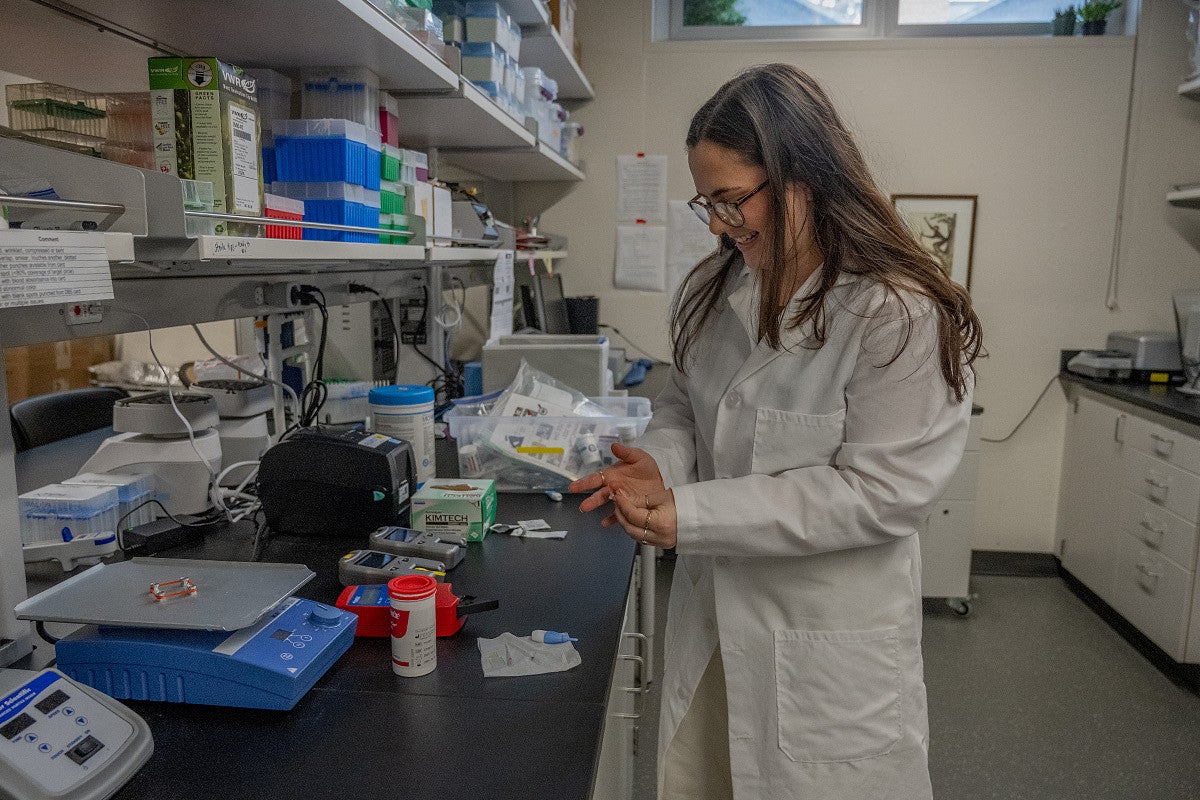

They continued chatting, trading stories while he waited to get his finger pricked. Cholesterol, blood glucose and hemoglobin can all be measured from a few small drops in the field, providing insight into health and nutrition. After collecting biomarkers, it’s survey time as participants answer questions about past traumatic events, health conditions, disabilities, illnesses, and housing history.

Each month, the research group returned, as did the man and his canine companion, long after doing his part in the study. July marked the end of data collection at the park and the last time she encountered the familiar duo.

Five months later, at Bridges on Broadway, the research group took the next step in identifying the factors which influence the health of people experiencing homelessness, by tracking participants as they transitioned into permanent supportive housing.

Sitting in the community room, she met a clean-shaved, joyful man, eager to start a new chapter.

At his heels? Duchess. The owner was unrecognizable, transformed from head to toe in appearance and disposition. Even though her research didn’t cause the change, it moved her. Albiani recalls petting the dog in tears.

“Just to watch the arc of his story, to know someone when they are at one of the lowest points in their life and then watch them start to move out of that, was incredible,” she recalls.

Now in her senior year, moments like this give Albiani strength to push through frustration. Research in homelessness can feel overwhelming, she admits. “There’s not a better perspective on how to fix the issue now,” she says. “It's horrible that it’s been pervasive in our society for a long time—and it's getting worse.”

For Albiani, frustration is not a deterrent, but proof she is tackling problems that truly matter.

She has spent a lifetime actively thinking about solutions to complicated societal issues. Through the 10-week Prison Education Program she took part in, half her class was incarcerated. She explored concepts of growth, forgiveness and punishment. In another CHC class, “Solutions to Our Wicked Problems” taught by Nicole Dahmen, she chose to investigate youth recidivism.

Throughout, homelessness has remained at the forefront of her mind. In her two years as a research assistant on the Homeless Policy and Health Project under professors Jo Weaver of UO’s global studies department and Josh Snodgrass of anthropology, she’s contributed to nearly every facet of the project. Albiani conducts interviews with participants, collects samples in the field, and performs data analysis.

As a multidisciplinary science major, Albiani has many different tools at her disposal. Through her vast skill set, she is able to approach a complex issue and break it down into digestible, solvable pieces. She’s methodical, and describes her research process as “obsessive.”

Research is not rushed. Albiani has time to sit with problems, wade through layers of evidence, and uncover hidden correlations—until the full story emerges.

“She’s always good at figuring out what’s needed, finding that missing piece,” Snodgrass says.

“You can't put a one-size-fits-all solution onto a complicated and diverse world. That just doesn't work,” Albiani explains. “I am not satisfied with the answers that are out there, because a lot of the time they are painted very black and white.”

Albiani grew up in Elk Grove, CA, where dinner-table conversations doubled as both a bonding experience and an impromptu debate club. At nine, she was analyzing TV commercials, discussing the state of the economy and delving into international politics.

In the Albiani household, “everyone is a loud one,” she laughs. However, in the family of six, Albiani was most determined to have her voice heard. In passionate arguments with her sisters, “I would never accept defeat,” she recounts.

Albiani’s father, a lobbyist, had a talent for arguing both sides of any debate. He taught her an important principle: if you have an opinion, you'd better have evidence to back it up.

At 15, Albiani had taken his advice to heart, and started Extemporaneous Public Speaking through Future Farmers of America. By 2022, she was a state champion and a national semifinalist. On competition days, she would deliver a four- to six-minute speech on a random topic.

The thought of walking into a competition unprepared still keeps Albiani up at night. What soothes her, though, is researching a topic so thoroughly that there’s no contesting her knowledge.

“The fact-vending machine,” as her family called her, filled five public speaking binders, 100 pages each, with articles and policy briefings to prepare for questions on cows, taxes, water and immigration. The list goes on. Often in heated debates at the dinner table, Albiani would run upstairs, grab a binder and flip to an article that proved her point.

“Once she gets interested in something, she tends to go all-in and know-it-all,” her mom, Beth Albiani, says. A key to Albiani's early success was learning to study opposing viewpoints.

“I knew what I was supposed to say to answer questions, to please the people that would be judging me, but in writing good speeches and learning about these complex issues, I often would need to understand the counter-arguments,” she says. True understanding of societal challenges, she believes, falls somewhere in the middle.

Seeking an education that would support Albiani’s multi-layered thinking was a big factor when it came to her college decision. The interdisciplinary approach at the Honors College stood out immediately.

She remembers the fascinating material in HC 444H, Black Literature, Science and Reproductive Justice with Angela Rovak. “I finally understand these small classes, these intimate conversations: That’s what a liberal arts education is,” she reflects.

Stepping in to build a website for Weaver her sophomore year showed her how anthropological research could bridge many of her interests. That moment launched Albiani into the heart of the policy project.

“It’s those moments when you see yourself in someone, or see your story, or are reminded of someone that you love, that remind you that we’re all just people. I think it’s a lot bigger than being a researcher. It’s just about being a good neighbor and helping out people in your community.”

She is now wrapping up her CHC thesis project, Factors Associated with Food Insecurity Among People Experiencing Homelessness, based on research from that project.

Albiani approaches conversations about food access with an analytical and a critical eye, aiming to fill gaps in public understanding.

“Most issues involving people can’t have one good answer because people have diverse interests and diverse challenges,” she says. For Albiani, intricacies are part of what makes the work so compelling.

She goes beyond statistics and finds nuance. Even with programs like SNAP, people experiencing homelessness are often still hungry.

“I haven’t yet analyzed our full dataset,” she notes, and is continuously working to finalize the full set of factors.

Her undergraduate research is only the beginning. Building on her thesis, she’s determined to continue exploring the many drivers of food access. In fall 2026, Albiani hopes to begin her journey toward a PhD in biological anthropology.

When asked what drives her to dig deeper, she responds plainly: “Someone needs to think about issues. If no one thinks about them, if no one appreciates different perspectives, then nothing's ever gonna get better.”