Finding balance around the brain

Year in school: Senior

Hometown: Beaverton

Majors: Neuroscience and Human Physiology

Minor: Chemistry

Coffee or tea: Tea. I'm staying off the caffeine until I need it in residency.

What's in the fridge: Rows of black tubs. I love to meal prep and will make all my meals for the week on Sundays. Oh, and apples, hummus, and almond milk, of course.

Song on repeat: Counting my Blessings by Seph Schlueter

Advice for new CHC students: The thesis process is very doable and extremely rewarding. Do it on what excites you. And present your work. Whether it’s a final project for a CHC class or research for the Undergraduate Research Symposium each year, it’s great practice and there are awards.

Tanner Rozendal remembers the first-grade gym class like it was yesterday. Students formed a line on the Terra Linda Elementary School gym stage to play kickball. He was next up when suddenly, he was pushed off the stage. He hit his head and blacked out. When he came to, his nose was bleeding. He was taken to the principal’s office and then his mother picked him up after school.

The next evening, while attending a semi-pro hockey game, he told his mother that his head hurt. That’s when his family rushed him to the emergency room. Doctors told her that he had a concussion and a crack in his skull from the impact with the floor. “He could have died during the night,” recalls his mom, LeLisa Rozendal.

The treatment that followed created a level of confusion for the family. They say they were getting little guidance about how to treat the injury. His parents worried that he would have to repeat first grade because his concussion symptoms lasted more than six months.

“I remember car rides hurt because there was so much light,” Tanner Rozendal recalls. “I could not do anything without my head hurting. No friends, school, sports. I was isolated from all of my identities as a first grader.”

Amidst the confusion, Rozendal became curious about how the brain works.

It was a feeling that stuck with him. Today, he’s a Clark Honors College senior who is double majoring in neuroscience and human physiology with a minor in chemistry. The seeds of his experience getting a concussion as a kid have blossomed into someone with a drive to study the brain and help people.

Hailing from Beaverton, Oregon, Rozendal is the older of two children. His mother works as a civil engineer for the city of Salem, and his father is a structural engineer at JHI Engineering, a private firm in downtown Portland. He remembers a childhood full of activity – his passion for hockey was sparked at age four.

“We would travel all the time for hockey to Canada,” he says now. “My dad and I loved poutine. We found the best poutine at Canadian Costco. So, we would go buy hockey stick tape and then go to Costco to get poutine.”

Rozendal’s mother recalls that “he was always a thinker.” Inspired by his prolonged recovery from the concussion, he not only wanted to learn about the brain, but he also wanted to understand the processes and procedures behind it.

In sixth grade, he remembers that a close friend always talked about becoming a neurosurgeon. For Rozendal, it translated into setting his own goals about a future in medicine.

In high school, he volunteered in one of Kaiser Permanente’s intensive care units in Beaverton. During the pandemic, the hospital needed all the help they could get. He saw a range of people who were critically ill. Many suffered from COVID-19. Some experienced kidney failure, while others were on ventilators. “It was an amazing opportunity to have the dichotomy of learning what COVID was while working the front lines,” he recalls.

He also worked as a server at a retirement home in Beaverton. He wanted to know more about the people he was interacting with, so he made a point of memorizing their meal orders. He developed a strong bond with a couple living there, and when they learned that Rozendal was interested in medicine, they showed him the husband’s medical charts. “It was like a weight off her shoulders to talk about her husband’s condition,” Rozendal says.

Another group of residents took Rozendal under their wing and taught him how to play bridge. He was so admired by the retirement home residents that some tried to set him up on dates with their granddaughters.

At the same time, Rozendal had his own health challenges. He contracted COVID-19 in 2021 while volunteering at Kaiser. The diagnosis revealed an underlying autoimmune disease called scleroderma. And he was taken by the care he received from his doctors and nurses, noting that he experienced a holistic model of care. The support showed him that life-changing results can happen when people in the medical field collaborate closely. It solidified his drive to go into medicine.

“I was supported by a team,” he says now. “I want to be part of that team in the future.”

Rozendal got into the Honors College and came to UO because of its established neuroscience major. He crafted his first-term schedule so he could take an Honors College course with Nicole Dudukovic, a CHC core faculty member and the neuroscience program director.

He also enrolled in biology Professor David McCormick’s “Science of Happiness” class. By the end of fall term that year, he was conducting research in McCormick’s neuroscience lab where he worked on mice to understand the mechanisms of brain control.

The summer after his freshman year, Rozendal interned at Oregon Health & Science University in the Kreth lab. That’s where he learned about the composition of the oral microbiome. The result was he participated in the publishing of two papers on polymicrobial diseases and oral biofilm – a rare feat for a rising sophomore.

At the same time, he developed a presentation to help students understand how they can maximize their research experience. Rozendal’s materials are used extensively in the onboarding process for students who are joining a lab.

Dudukovic says he is a model example of a leading student. “I sometimes feel as though he is offering me more support than I am offering him,” she says. “He has given me the pre-med resources he created, expressed willingness to help some of my other advisees who were struggling with organic chemistry, and offered me tickets to the hockey games he referees.”

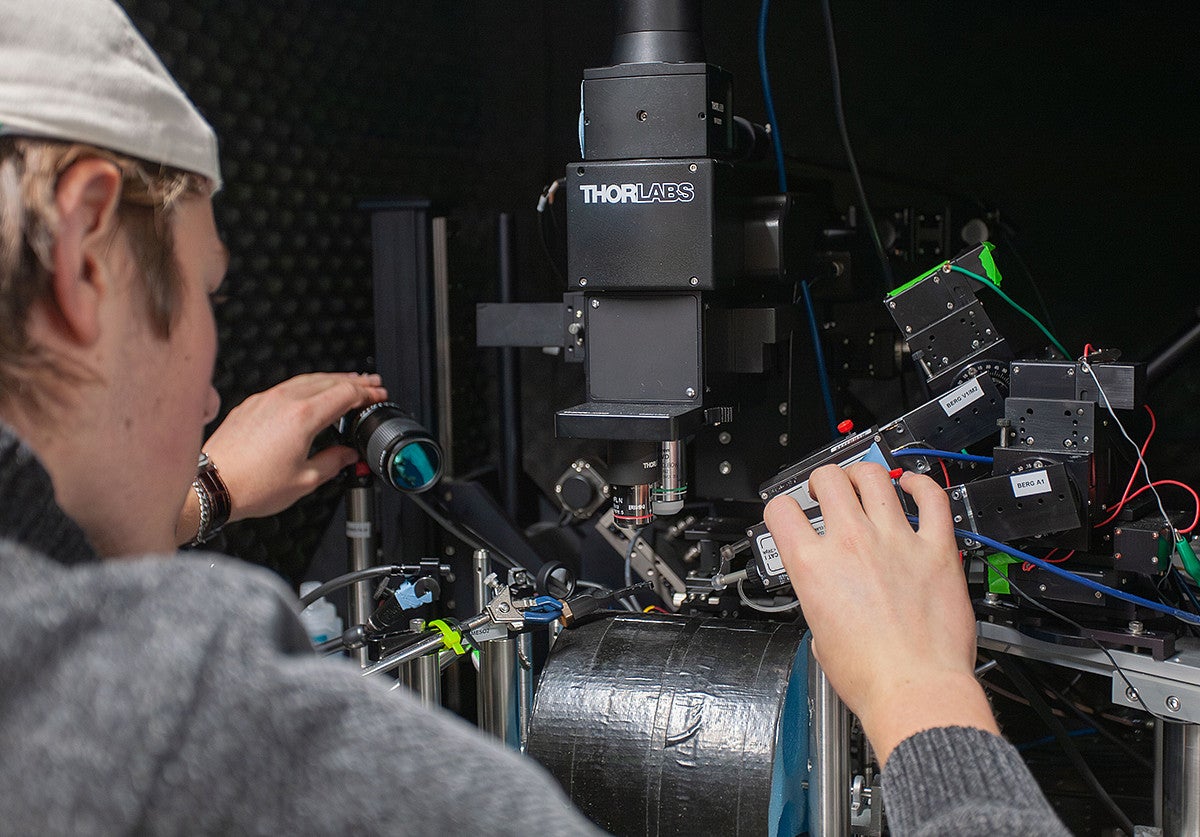

Currently, Rozendal is working on his CHC thesis, where he is investigating how the size of the pupil of the eye can reliably predict an absence-epilepsy seizure before it occurs. The lapses in consciousness that characterize absence-epilepsy may be predicted by pupil size, a proxy for the internal state of the brain.

He’s also conducting research on how neural circuitry in mice is responsible for triggering absence-epilepsy seizures. Using Python programming language, Rozendal coded an algorithm that records the pupil size before a seizure. His research found a reliable decrease in pupil size prior to a seizure.

In the long term, Rozendal hopes to apply his findings to clinical studies. He plans to utilize special glasses to monitor pupil size in humans. The glasses would stimulate the vagal nerve, which controls vital functions. Stimulation from the glasses could potentially stop brief lapses in consciousness before they even begin. This application could serve both people suffering from absence epilepsy, as well as people who are prone to zoning out.

He’s found other avenues to support his training. He works three days a week as a phlebotomist at UO Health Services, drawing blood from students who are facing health issues. Sometimes, he’ll see someone wave at him while walking across campus because they remember him as the person who not only drew their blood but also took the time to get to know them.

When he isn’t conducting research, Rozendal serves as president of UO’s Medicine and Ministry Club. He says he has tripled club engagement during his tenure. Additionally, he founded and organizes Literature in STEM, a book club, and he referees UO hockey club matches. He volunteers once a week curating health and wellness resources at Sponsors, Inc., a Eugene nonprofit that provides housing and job support to previously incarcerated individuals.

His interest in carceral health and policy was sparked by CHC Professor Anita Chari’s Inside-Out Prison Exchange class, “Autobiography as Political Agency.” Discussing identity alongside 13 UO students and 13 incarcerated students at the Oregon State Correctional Institution changed his perspective on interpersonal relationships, he says.

“Because I was in the Inside-Out class, I learned the importance of relationships for healing and wellbeing,” he says. “The foundation of medicine is relationships. The foundation of prisons is stripping people from their relationships.”

He credits the Honors College as a place where he can pursue his interdisciplinary passions and further develop community. “In my STEM classes, we are constantly exposed to the same cohort of 200 students,” he says. “But in the Honors College, I interact with different people in small classes.”

“In my STEM classes, we are constantly exposed to the same cohort of 200 students, but in the Honors College, I interact with different people in small classes.”

Exposure to classes such as Black feminist literature affirmed his commitment to pursuing a master of public health alongside a medical degree. Ultimately, Rozendal aims to practice medicine as a reconstructive plastic surgeon.

Following graduation in June 2026, Rozendal plans to take a gap year. He hasn’t decided yet where he wants to go, but he’ll take the time to examine programs that encourage people who are seeking both a masters and a medical degree. “I want to use my strengths to support other communities,” he says.

Beatrice Kahn is a senior double majoring in history and English in the CHC. This story was written as part of her advanced-level public writing seminar on neuroscience journalism, taught by CHC core faculty member Nicole Dudukovic. The class voted Kahn's story as one of the top in the class to be submitted for publication in The CHC Post.