Major: Asian Studies

Co-author, Scouting the War on Poverty: Social Reform Politics in the Kennedy Administration

Urban Ore

At age 18 in September 1958, I migrated from West Virginia to the University of Oregon. Nine months before, I took a day off from work to nurse an injury, a chemical burn from cleaning carbon-encrusted walls inside a big mixing machine at the giant aluminum plant where I worked as a new hire. The only way I could do the work was to wrap my legs around the mixing blades. It was a frightful job: what if it turned on somehow?

Another newbie my age replaced me the day I stayed home. While he was inside, the machine turned on. He died instantly. It should have been me. Fate and chance said no. To what end?

I worked hard, saved, and left West Virginia. I brought my working-class heart and soul to the honors college ethos. Not a self-less lad, I was molded by caring HC professors, including Lucian Marquis, to start giving back right away.

With other HC freshmen, I cowrote an irregular column for the Oregon Daily Emerald called “We Dissent” that criticized unequal treatment of women under in loco parentis. The housemother system on the UO campus was dismantled a few years later. As a senior, I was the yearbook’s poet, lamenting the loss of privacy as we entered the cyberage. In 1963, as a grad student in East Asian Studies, I joined the first-ever Eugene demonstration against the escalating Vietnam War. I became a community organizer—in Lyndon John-son’s war on poverty. With my thesis advisor, I wrote a book: Scouting the War on Poverty: Social Reform Politics in the Kennedy Administration. That book became my doctoral dissertation.

“Honors College” hovers like a medal with no frame below “Bachelor of Arts” on my diploma. There were six of us in the HC class of ’62. I was saved; then selected. Why? To what purpose?

I harnessed coursework to study social change and social movements cross-culturally. I wrote and published reports, essays, and reviews drawing from all sorts of academic domains. Applied science became a pathway to giving back. The teachers who hired me were practical idealists: entrepreneurial academics who created institutions like the School of Community Service and Public Affairs.

Since then, I have focused on key questions: inquiries to inform choices between adaptive options for social change. The big take-away from the honors college: neither academic disciplines nor the university should ever be a barrier to learning, or to the joyful pursuit of key questions.

“ The big take-away from the honors college: neither academic disciplines nor the university should ever be a barrier to learning, or to the joyful pursuit of key questions. ”

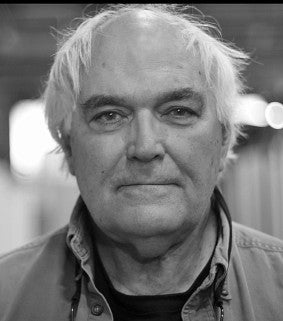

— DANIEL KNAPP

While I enjoyed a stint as a professor, I could see things changing. Courses I offered morphed from General Sociology to Twentieth-Century Homesteading. After seven years, I left academia for good.

While “retired” from my professorial duties, I helped the Oregon Country Fair pivot from anarchy to dictatorship to democratic profit-sharing corporation and responsible landowner. Pushed out of Lane County government for proposing reuse and recycling businesses at all county transfer stations, I hitchhiked to Berkeley. I became a scav-enger at the city’s dump while cofounding Urban Ore, Inc., a reuse and recycling enterprise like the ones I proposed for Lane County.

I’m for discipline, not against it. Business, which I have done full-time for 34 years, is discipline with a big D. That’s “D” as in “Don’t Do a business if you Don’t want Discipline.” With my wife, Mary Lou Van Deventer, an environmental journalist, I manage a resource-trading venture that is open 360 days a year. Urban Ore keeps more than 7,000 tons of resources out of area landfills annually.

Providing recycling services is a rewarding way to give back. People all over the globe want to stop putting discards into the land, air, and water by conserving them for productive use. Recycling, reuse, and composting are progressive and conservative at the same time. Today’s recycling movement began in 1970. By 2004, the US Environmental Protection Agency reported that American recycling hit $225 billion, equal to the gross income of the US auto industry. Today it is even bigger. I’ve helped create an industrial colossus.

Every country has people working on “Zero Waste: No Burn, No Bury.” My biggest intellectual contribution to this global enterprise is a theory of total recycling based on experience as a landfill scavenger leavened with an elite education from the Clark Honors College. The core concept is a set of 12 market commodities that describes the entire discard supply as resources, not wastes. In 1995, while in Aus-tralia as a consultant, I merged total recycling with Canberra’s idea of zero waste (same thing) and brought Canberra’s zero waste message to the USA. Zero waste quickly went viral on the new Internet.

To join the zero waste movement is to make uncounted billions of tons go away, legally, and without polluting. It’s hard work. Much comes in dirty. The work requires a judicious mix of technology and well-trained and motivated labor. It is brainy work, and brawny. I love that mixture.

Recyclers compete with wasters for the same resources. Wasters waste them by burning and burial; we conserve them. Recyclers are winning the industrial competition; wasting is a sunset industry.

I still ask and answer key questions. A big part of my writing becomes policy or informs policy decisions. Some best bits are archived on Urban Ore’s website if people want to enjoy some fruits of the intellectual garden that sprang up when I chose to give back what I learned even as I was learning it.

Summer 2014