She’s not crying over spilled chemicals

Hometown: Myrtle Creek

Current obsession: Trying new things. Recently, I have been exploring some interests of mine: making bread, playing guitar, shaping clay, sewing quilts.

Guilty pleasure: Looking at houses online. It will probably be a while until I own a house, but I like to imagine what it would look like.

Favorite book: If cookbooks don't count, then "Big Panda and Tiny Dragon." It's about friendship, patience, courage, and believing in yourself.

Favorite class you've taken at the CHC: Definitely the Malaria class I took my freshman year, but I am excited to be taking a class with Lindsay Hinkle, Verifying the Viral: Investigating Science on Social Media, that aligns with many of my interests.

Favorite album: Noah Kahan's "Stick Season" (and all the collabs he has done). His songs just resonate with me, so when I listen to them, it evokes a lot of emotions.

The anxious questions were familiar to undergraduate researcher Dante’ James as she led a tour of the University of Oregon lab where she studies bacteria and fungi on the skin.

“What if I’m not enough to apply for this lab?” a student in the group asked.

They were visiting from the university’s Women in Science and Math Academic Residential Community, designed to help new female-identifying students form relationships and find support in pursuing science, technology, engineering and math-related fields.

“I’ve also been in their shoes,” James says. “It can be really intimidating to get into STEM, or research, or try anything new.”

James reminded the tour group that like doing research, finding a sense of belonging in the lab is a learning process.

“I explained to them that I joined the Barber Lab before I even took Gen Bio – I had no clue what I was doing,” says the CHC junior and multidisciplinary science major. “With my mentors here, I’ve learned to be independent, and it’s been great, but there've been embarrassing moments where I’ve spilled chemicals all over myself.”

Whether it’s a spill or a rough grade on a test, James has learned to accept life’s ups and downs and move on. “I’m not giving up on myself,” she’ll think. “Everything’s gonna be OK.”

James has bigger problems to worry about. Specifically, as a global health minor, she’s focused on studying immunology to tackle major problems like pandemics.

“Global health has always interested me because it’s very tied into being a part of different identities,” says James, who is Vietnamese-American. “With the pandemic especially, that really had me thinking about all these different ideas of intersectionality.”

Last summer, James interned at a pharmaceutical research company in Vietnam. It gave her the chance to partake in a new aspect of global health and immerse herself in Vietnamese culture as she spent time with family who live in the country. She also realized that belonging anywhere is more about having confidence in yourself than about how you identify.

An intersectional identity

The daughter of a Vietnamese mother and an American father, James grew up in Myrtle Creek, a community in rural Douglas County, the middle child of three siblings.

As a person of color in a predominantly White community, James was often the only Asian-American in the room. At times, she says the expectation to represent all Asians was “a lot.”

“I remember being so disgusted with how Asian people, including myself, were treated during the pandemic,” James says. She remembers being asked by a longtime friend how it felt to “start a pandemic.”

James yearned to be part of a community in which she felt belonging. Getting involved was one way she made a space.

In high school, joining the Future Farmers of America club taught her what it meant to be a leader. Quickly elected vice president, she fell in love with public speaking. The club advisor coaxed her into lots of speech competitions, which sometimes ended in tears, but more often, she triumphed.

“That was a real-life lesson for me, that I could learn from my mistakes and do better the next time around,” James says, “and if not, that was OK, too. Through this, I was able to support more people who were like me, and just needed that extra little nudge.”

She also served on then-Oregon Governor Kate Brown’s Behavioral Health Advisory Council as a youth specialist. “It felt like I was the representative of rural communities, students, and the diversity rep at the same time,” James recalls. “But it was still very important to me to be there to advocate for mental health care, especially for these underrepresented populations.”

Around the same time, a spark was catching in James’ high school biology classroom. Taught by a college professor, the class was both encouraging and stimulating.

“He was one of those teachers that thought that no question was a dumb question,” James says, “and as a person with a lot of questions, that helped facilitate my curiosity.”

When it came time to think about college, James’ options were dependent on scholarships. UO awarded her the Stamps Scholarship, which would cover all her expenses and offered her admission to the Honors College. James also got additional funding for academic enrichment. In her head, she was already spending the money: she’d get to study abroad in Vietnam.

An Honors College 101 course, Malaria: Science, History, Ethics, Technology, introduced James to the interdisciplinary field of global health.

Melissa Graboyes, an associate professor of African history and global health in the Department of History, taught the course. James is now part of Graboyes’ Global Health Research Group. Graboyes says mentoring students in the group gives her hope.

“In order for future global health workers to do better, they'll need awareness of the history of places, language competencies, and sensitivity to culture,” Graboyes says. “Those aren’t always strengths of natural science programs. The beauty of the Honors College curriculum is that it’s well rounded and equips students to think about difficult issues from a variety of vantage points.”

James says living through the pandemic revealed the ways in which our society falls short. “There is so much that can be accomplished if we work together; however, many fail to look past differences,” she says. “Global health is a very multidisciplinary field, and we need it to be like this. We need more discussion, more integration, and more collaboration.”

Another class, Students of Color Opportunities in Research Engagement (SCORE), helped James claim her space in the research community quite literally—it helped her find the Barber Lab.

“Dante’ is curious by nature,” said Nadia Singh, the biology professor who teaches the class. “In research, that can be one of the most important things—being inquisitive. Dante’ was also a natural leader in SCORE.”

Singh says helping to cultivate a sense of belonging for students of color in science has been the highlight of her career. “One of the comments I hear from students every year is that they didn’t see themselves as scientists before, and as a result of SCORE they do.”

Belonging to herself

During the summer of 2023, UO’s GlobalWorks program connected James with an internship at Horus, a research contractor in Vietnam that conducts pharmaceutical studies.

James worked on a clinical trial studying the efficacy of a vaccine for hand, foot and mouth disease, and its effects on immunity. The disease, one of the top contributors to morbidity in the country according to the World Health Organization, causes mouth sores and rashes, is spread through close personal contact and primarily affects children. She also studied disease protocols and visited the CDC and rural clinics that treat the disease, where she met doctors and researchers.

“I took a lot away from the research,” James says, because it occupied the middle ground between her lab work and coursework. “It’s like, ‘OK, you’ve developed a drug, but you’re not going to disperse it widely yet – you're testing it.’”

Uyen Hong, Horus’s CEO, guided James on a dawn-to-dusk field trip around Vietnam’s provinces. Between stops on their itinerary, they joked in the van and ate rambutan from roadside vendors. She told James about everything from provincial culture and customs to a professional path James could follow to work her way, step-by-step, to the top of the industry.

“As a woman, she was very conscientious that it’s difficult to get into the healthcare industry sometimes,” James recalls.

As a member of the Diverse Ducks program, in which students create content to share with the UO community that reflects how they experience intersectionality abroad, James wrote blog posts at the beginning, middle and end of her experience, including a month of visiting family and sightseeing with her mom and grandmother.

She hoped to blend in more in Vietnam. But being there showed her that even after experiencing racism in America, she could be "not Asian enough.” She still stuck out as an American.

Paradoxically, she also experienced racism in Vietnam from her fellow American interns. Because she speaks some Vietnamese, she was used insensitively to make arrangements for them. She says they showed their bias through cultural prejudices, White saviorism, or a privileged ignorance of realities in the country where they were guests. For James, the experience was infuriating.

Though confusing and sometimes disappointing, James' time in Vietnam helped her find her position at the intersection of race, culture, and experiences, she writes in the blog.

“In terms of my identity, I learned that I can belong to both cultures, American and Vietnamese, although perhaps not one entirely,” James writes. “As a mixed-race individual, that is just something I have to accept and understand.”

Making space for others

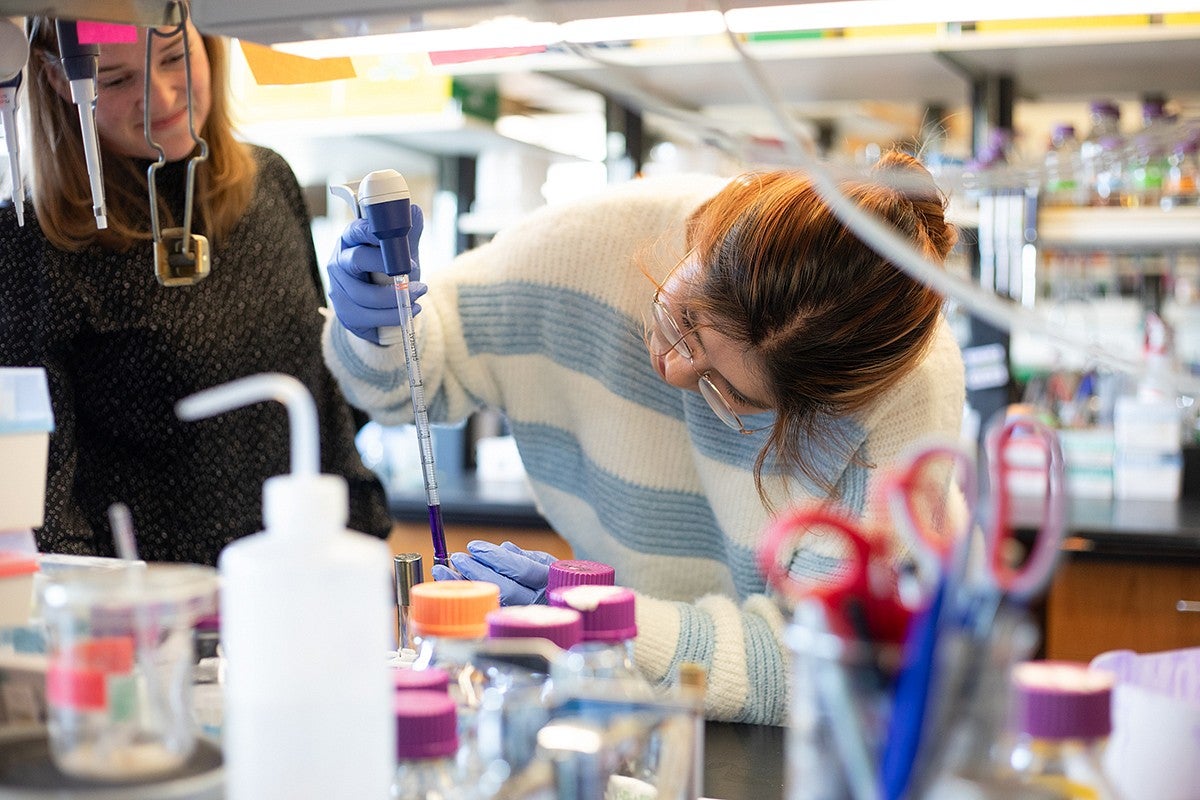

When postdoctoral researcher Caitlin Kowalski trains new students in the Barber Lab, they begin by practicing hands-on techniques to build confidence before diving into the concepts behind them.

“With Dante’,” Kowalski says, “that part was really short.”

James is never one to shy away from new experiences. “I try to channel her myself,” says Kowalski, who calls James’ confident attitude “the Dante’ approach.” It goes like this: “I can do this. If something comes up, I’ll figure it out.”

A year later, James is sending Kowalski research papers, suggesting their findings may be connected to what they are seeing in the lab and proposing new experiments. “That is so far beyond where she started,” says Kowalski. “It’s grad-student level thought.”

“There is so much that can be accomplished if we work together; however, many fail to look past differences. Global health is a very multidisciplinary field, and we need it to be like this. We need more discussion, more integration, and more collaboration.”

One of James’ favorite things about working with Kowalski is how she finds ways to center James’ academic interests in the lab, whether that’s coding, skin care or bacteria art. As the two explore ideas for James’ honors thesis, she’ll have the independence to design experiments that follow her own curiosity.

Recently, James stepped up to give a lab tour after hours when no one else was available.

“I thought, ‘this is amazing.’ I’m so proud that she feels she is a member of this lab, this community, that she can show people around it. That’s ownership, and that’s something I admire at that age and in that position,” Kowalski says. “But also, I know how busy she is.”

From a young age, stepping forward has been a way of life for James, including training as a firefighting cadet in her hometown. At UO, she joined ASUO as the first-year rep. In the Barber lab, she proposed a glove recycling program that will become part of a new campus-wide sustainable labs initiative. Last fall, she helped organize a basketball fundraiser to benefit three organizations that work to improve wildfire resilience across the state.

At the same time, she’s thankful for the mentorship of others along the way. Now, she looks for chances to give back to the communities that have nurtured her—like giving lab tours to young female students. “If you’re going to take space, you’ve gotta make space,” James says.

A version of this story also appeared in Oregon Quarterly.