From the ground up

Guilty Pleasure: Dark chocolate pistachio ice cream

Favorite Movie: Guelwaar from Sembène Ousname

Coffee or Tea: Neither. Both, and please serve the tea with mint

Why I teach at the CHC: The neat community of students, faculty and staff. One thing you would never guess about me: I played professional soccer for a year.

Jean Faye remembers the reaction of his friends when he told them he was dropping out of the veterinary medicine program in Dakar, Senegal, where he was attending college.

“They said: ‘this guy has gone crazy. He’s mad,” Faye recalls.

At the time, Faye’s home village of Toucar was being ravaged by cholera. “People that I grew up with, played with, were dying,” Faye says. “And it was avoidable. I could do something.”

He began to educate his village and other nearby villages about sanitation techniques, along with the steps they could take to prevent the spread of deadly infectious diseases. He was able to see an immediately high success rate from his efforts – people in his village were contracting cholera less and less.

The experience changed the trajectory of his life. He saw evidence of what he already knew: the education and knowledge that he had developed could be used to improve the lives and living conditions of his people, so he pressed ahead.

He created a self-help organization called the Association of Farmers in Toucar, which brought together local farmers in order to diversify the productivity of agriculture. The organization helped introduce modern farming techniques (building rainwater harvesting basins, market gardening and horticulture, digging wells, etc.) and made sure people understood the impacts of climate change on food production.

He saw how some organizations in his native country took a more colonialist approach, either by being unaware or insensitive to indigenous practices. “Indigenous people know,” he says. “They’ve been surviving for millions of years. We should learn from them, not impose our knowledge on them.”

Much of Faye’s research focuses on methods like rotational farming, intercropping, and agroforestry, all of which help farmers become successful in the face of climate change.

A passion for farming

Faye’s passion for farming can be traced back to his early childhood. He grew up in a large family with his parents and nine siblings. They lived on and worked a farm in Toucar, part of an indigenous ethnic group called the Serer people.

As a child, Faye would go out into the wilderness and explore, looking closely at the plants and soil. He saw how different kinds of soil promoted plant growth. “I would collect soil and bring it home,” he recalls fondly, remembering how he was fascinated by the different tints and textures.

During the rainy season, Faye and his family would work at their farm from sunrise to sunset. They grew a variety of crops, rotating them regularly and using livestock to fertilize the soil in off years. The main crops were millets, sorghum, peanuts, beans, okra, cassava roots and squash.

After high school, Faye wanted to become a veterinarian, so he went to school in Dakar before returning home. When the health crisis at home was contained, he decided to go back to college. He went to University of California-Santa Cruz to take coursework in organic farming systems. “I learned some things, but I really don’t think I learned enough,” he says.

He enrolled at Berkeley to study environmental science policy and management, working as a research assistant under Professor Miguel Altieri, a groundbreaking agroecologist. He finished school in 1998, working stints at a California biotech company and as a landscaper. Later, he met the woman he would marry and they started a family.

Dennis Galvan, now a UO professor of political science and global studies and the vice provost for global engagement, had met Faye earlier and done research with him in Senegal. He suggested that Faye come to the University of Oregon for his PhD.

With UO’s focus on environmental studies and sustainability, Galvan thought Faye could thrive in Eugene. Faye earned a master’s in international studies and a PhD in environmental sciences with a focus in geography. His dissertation tied his passions together in a study called “Farming and Meaning at the Desert’s Edge: Can Serer Indigenous Agricultural and Cultural Systems Coevolve Toward Sustainability?”

Galvan was the chair of Faye’s dissertation committee. “There are topics, there are things you write about, and then there are things you live and breathe,” Galvan says now. “Things you devote your life to. Faye was writing and teaching about a topic that pulls in his whole life experience, as a farmer, as a community organizer, as a public health advocate.”

With his PhD in hand, Faye moved to Kentucky to work as an assistant professor at Centre College. He spent six years there but wanted to be back in Oregon.

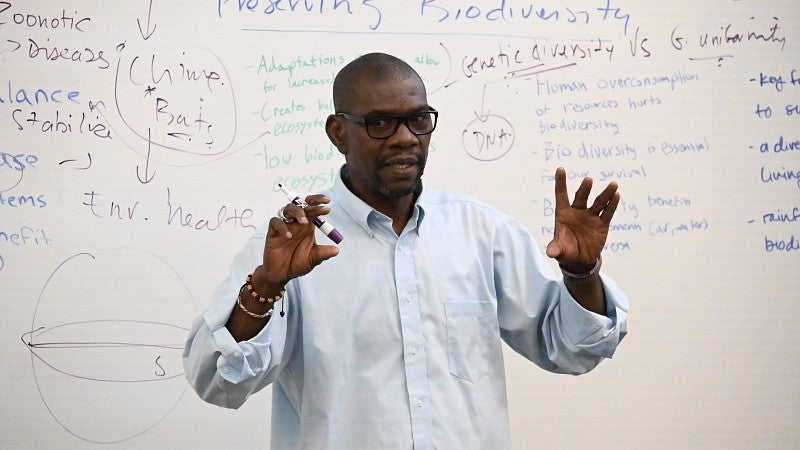

Armed with the experience of teaching at a small liberal arts college, Faye was a top candidate to teach at the Clark Honors College when the position opened. “He has this deep love of the land, and people,” says Carol Stabile, dean of the Honors College. “He just brings so much experience and such a keen and analytical eye to his teaching and research.”

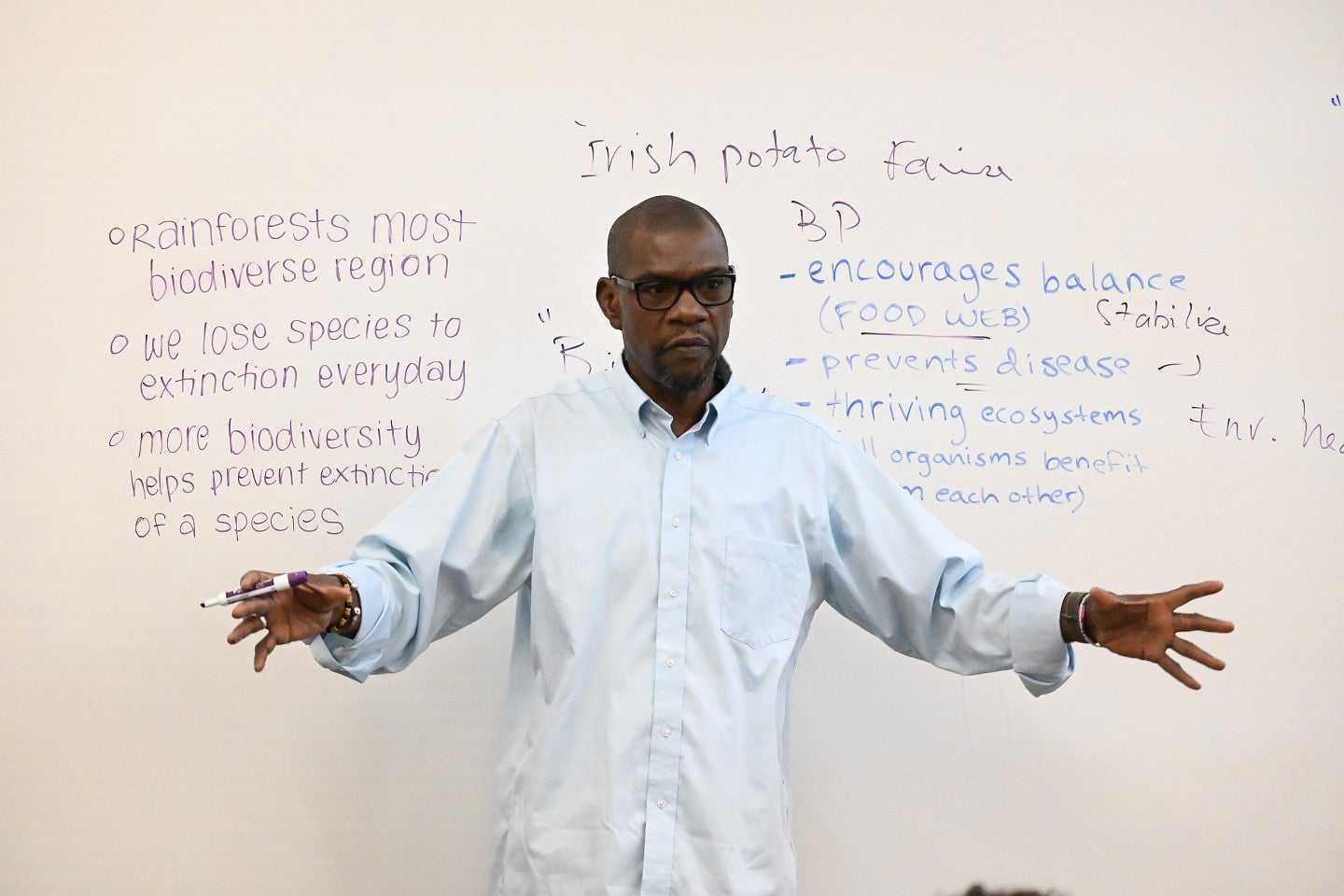

Today, Faye is teaching “HC 241: Environmental Problem Solving” and an Honors College thesis orientation class. He also is continuing his research about the Serer people and their farming traditions. He is working on a project on the relationship between fictive kinship and environmental resilience in Senegal with Galvan.

Faye’s teaching and research intertwines in a very natural way. He believes that a large part of his role as an educator is to help his students learn more about the elephant in the room in environmental science: climate change.

People need to “live on this planet Earth sustainably,” Faye says. “Think of the future generations that come after. Think of leaving the Earth in a better status than (we) lived it.”

“Indigenous people know. They’ve been surviving for millions of years. We should learn from them, not impose our knowledge on them.”