Grief 101

Maya McLeroy is a sophomore in the Clark Honors College, majoring in journalism and advertising.

When I left home 18 months ago for my first year in college, my grandfather gave me four things: an alarm for my keychain, a small notebook, a quick hug, and five words in a shaky voice that had always been steady: “Take care of yourself, Maya.”

Clark Honors College, just two hours southeast of my family’s farm, was becoming my new home. The places are vastly different and I knew it would take a while to get used to the rhythm of college life.

My entire life was marked by meals at my grandparents’ house next door – I fondly remember “Pop” starting so many mornings with a breakfast of waffles for me and my younger brother. The scent of fruit ripening and the low hum of tractors during harvest are fixtures in my memory.

I was ready to trade that for UO’s sweeping sea of green and yellow, dodging people in the passing period between journalism and Italian classes, and takeout dinners with my roommate on the floor of our cramped dorm room.

I missed my family, but I found anchors to keep me grounded. I love poetry and I thrived in my Honors College 101 class with Professor of Practice Barbara Mossberg, known to her students fondly as “Dr. B.” Pop knew how much I wanted to explore in creative writing with her and I could always count on his texts, asking for updates about the class that ended with strings of exclamation points and “YOU GOT THIS” for emphasis.

Pop was always so thoughtful. When I was in high school, he and my grandmother gave me three books of poetry written by Louise Glück. Those books made me want to write with the emotional intensity she displayed. I sharpened my skills by writing about Pop – how he had a constant need for answers, how the wheels of his brain would never stop turning, and how sometimes I’d get embarrassed when he’d approach total strangers and just start talking to them.

If you didn’t know him and sat next to Pop at dinner, you would leave being his best friend. And speaking of food, this man never met a meal he wouldn’t eat. He would hum, compliment the chef, and then nod off at the table only to wake up in time for dessert.

When everyone was getting ready to leave the table, he’d wag his finger and say: “Ah ah ah. I have one more sip left.” He’d wait a few minutes, then take one long, dramatic sip of whatever was in his glass, and everyone was then excused.

I turned to Pop when my father was diagnosed with cancer during my freshman year of high school. Everything felt like it was in disarray when my dad’s health scare occurred. But Pop oozed optimism. He had worked in the medical field as a pathologist and explained everything about Dad’s treatment. And, of course, he’d make waffles for us while my parents went to medical appointments.

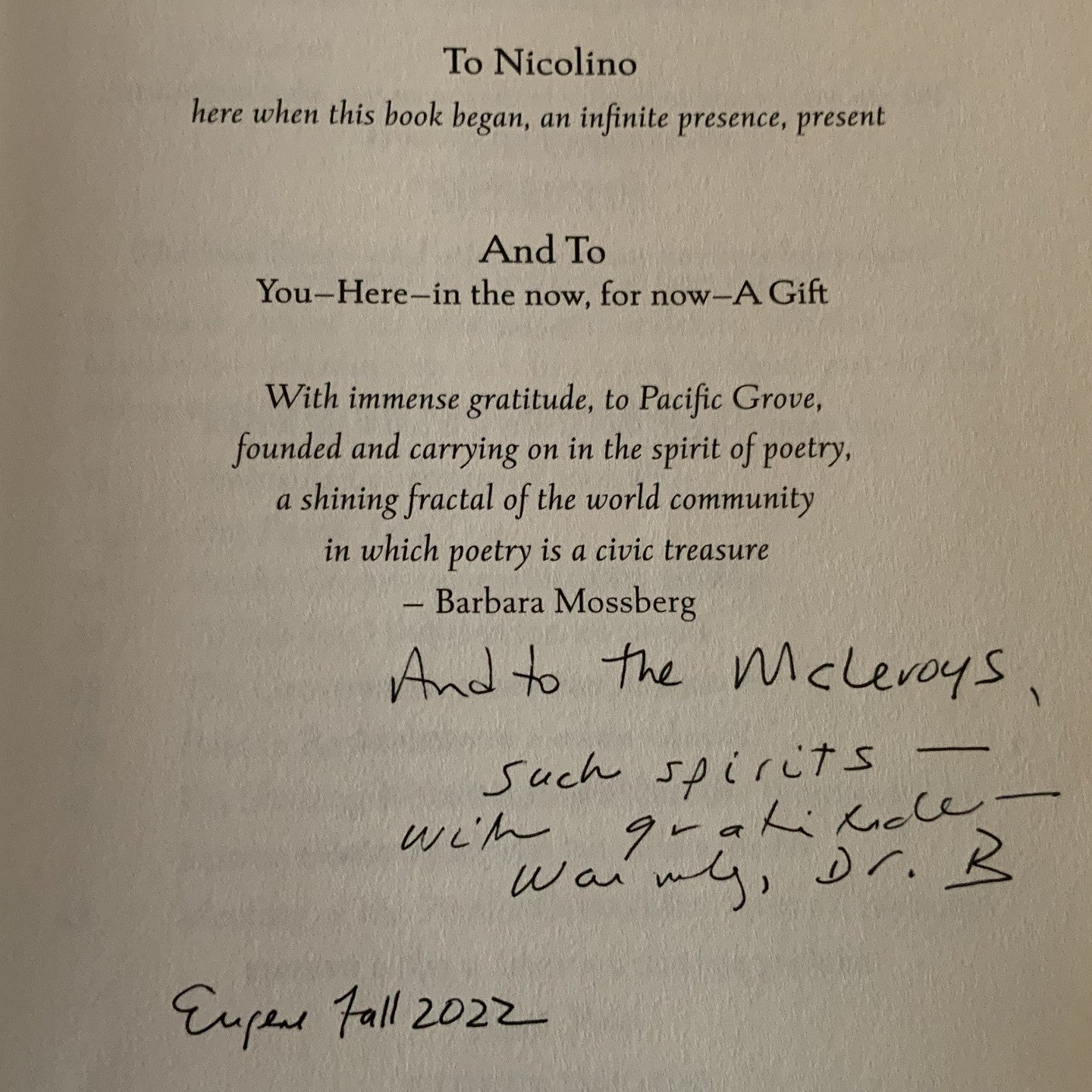

I still remember exactly how that morning – just one month after I’d started college – unfolded. I had waffles for breakfast in the dining hall, followed by an office hours visit with Dr. B where she gave me a copy of her book on poetry. We talked about my future in writing. And then I got a phone call and walked outside to see my mom pulled up to the curb with tears streaming down her face. She told me Pop had died that morning. I realized then that I hadn’t responded to the last text he’d sent me.

I spiraled, not knowing how to cope with such a massive loss. I had no idea what to do with grief. My mom had always told me that in U.S. culture, we don’t always deal with grief well. She learned this when my older brother, Max, died when he was 18 months old. My parents were sent dozens and dozens of hams by friends and family.

“A lot of people don’t feel comfortable sitting with grief,” she’d say. “But they do know how to send hams.”

With Pop gone, I needed a grief textbook I could dog ear, highlight, and annotate. If there was a “Navigating Loss 101” or a “Where To Put Your Pain” workshop offered, I would have signed up and sat in the front row.

I turned instead to Dr. B’s HC 101 class called, “Epic Influencers: Poetry, Leadership, and You,” where most of the essays I turned in often ended with stories about Pop. Part of being in the Honors College is knowing you can count on the faculty to be there for you.

“Tell me more about him,” Dr. B said in her feedback to me. So I did.

I wrote about how I remember that Pop whistled everywhere he went. I wrote about how following his death that I kept waiting for the sound of him to fill the room. And I wrote about how I would give anything to hear him say, “Let me have one more sip” one last time.

When my uncle was cleaning out Pop’s office, he found a poem I’d written while studying abroad on UO’s pre-freshman trip to Siena, Italy, which was led by Professor Kate Mondloch, a CHC faculty-in-residence. While there, I spent most of my free time sitting around a dinner table, eating food shiny from olive oil and laughing with new friends. On walks home, I noticed even more tables on the street with people packed in like sardines. I was absorbed by the sounds of their laughter, of glasses clinking, and of their harmonizing voices singing the songs of their contrade. I spent so much time thinking about these tables that I wrote a poem about them.

Pop had printed out the poem, underlined some of the stanzas in pencil, and kept it on his desk. It read, in part:

but for now, let me stay at the table a little while longer

to sip one last drink

& share one last toast

& one last glimpse

with the people I’ve grown

to love along the way.

my heart’s been cracked open;

my life’s grown so much bigger;

I’ve become someone new;

just by staying seated at the table.

At the time, I thought I was writing that poem purely about my month in Italy, from the perspective of an 18-year-old girl entering the next chapter of her life. Now when I read it, I do so through the eyes of my grandfather.

It took losing Pop to realize I’d been writing about the lessons he taught me this whole time. And it’s taken 18 months since his death to finally feel comfortable with my grief.

It took losing Pop to realize I’d been writing about the lessons he taught me this whole time. And it’s taken 18 months since his death to finally feel comfortable with my grief.

Sometimes, I still cry when I write about him, and there are moments when missing him hits me completely out of the blue. But I’ve learned that the only way to combat the grief is to look at it head on. The way to fill the hole loss creates is to make sure we don’t lose this moment, here, right now.

I hold on to all the beautiful things happening in Eugene, the things I’d tell Pop if I still had the chance: making waffles for my friend group on Sundays; writing poems and sharing them with Dr. B; and thinking about how the daffodils outside Chapman Hall have faces and that they are all pointed toward the sun.