A mother’s story fuels a lifelong career in women’s health

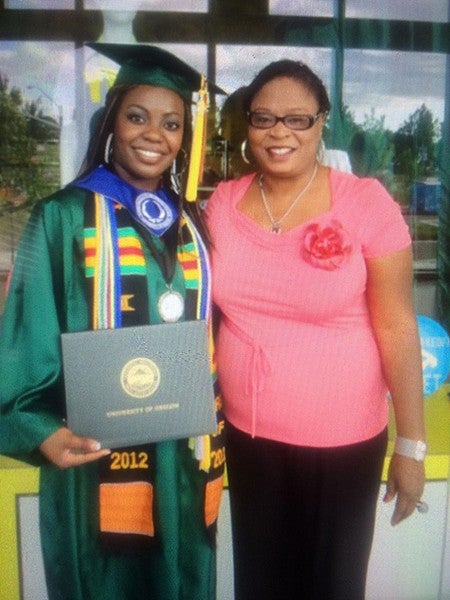

CHC Class: 2012

Coffee or tea: I’m actually a hot chocolate drinker if I am reaching for a warm beverage.

The one person you'd have to dinner would be: My maternal grandmother. She passed before I was born, but the loving stories that my mom shares about her make me wish that I could meet her.

What I’m listening to: “Cowboy Carter” by Beyoncé. I think it’s Bey’s best album yet. Aside from that, most of the time I’m listening to Afrobeats – everything from Burna Boy, Asake, Wizkid, Davido, Fireboy DML, to Mayorkun.

Favorite TV show: I’m really into crime TV. My favorite is “The First 48” on A&E. I use my critical thinking skills for most hours of the day, so it’s nice to watch mindless “reality” TV.

In my spare time I am: At a sporting event or at a local ice cream shop. I love ice cream...could probably eat it for breakfast, lunch, and dinner if I’m being honest. And, of course, sleeping – medical training can be tough.

Her memories of the landmark court case involving her mother are sparse, having faded into the background of her mind. Ann Oluloro was five years old when Lydia Oluloro—a single mother of two daughters—faced the threat of being deported from Portland to her native country, Nigeria.

Lydia Oluloro had been living in Oregon on a visa for some time when U.S. immigration officials sought to have her removed from the country. Ann Oluloro and her older sister, Tayo, had been born in the U.S., and their mother had divorced their father to escape an abusive relationship.

She sought asylum out of fear if she returned with her children to Nigeria, the girls would meet the same fate Lydia Oluloro had in her youth: female genital mutilation.

It was 1994, and in a landmark ruling, a U.S. immigration judge ruled in her favor. She could stay permanently in the U.S. and apply for citizenship.

Ann Oluloro attended the Clark Honors College at the University of Oregon and later became an obstetrician and gynecologist. Her mother’s experience served as a catalyst for Ann’s interest in medicine. In particular, her work as a gynecological oncologist fellow at the University of Washington aims to close the gap in women’s health, especially for Black women.

Ann Oluloro says what happened to her mother has instilled in her a drive to make a difference.

“It just had such a profound impact on my life,” she says.

The entire story played out in the national media – from The New York Times to the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post and the Tampa Bay Times. The Oluloros remember being visited by Dateline NBC for a feature, and they still get calls from law students who use Lydia Oluloro’s case in their research.

The case would set a precedent for the future of refugee women seeking asylum from female genital mutilation across the globe. The practice, according to the World Health Organization, includes the removal of external genitalia in girls for non-medical reasons. There has been a decline worldwide in the procedure in recent years, but its prevalence remains a public health concern.

Between her mom’s experiences with her health and her hard work to make ends meet for her two daughters, Ann Oluloro became innately aware of the disparities her family faced in the public health sector. “It was always seeing the constraints that women went through, but my mom always saying you can break through those constraints,” she says now.

Ann Oluloro graduated from the Clark Honors College in 2012, completing a double major in biochemistry and biology. She fondly remembers the small community feel of the Honors College, the friendships and connections she made, and the opportunities she had to be challenged academically. “It helped me become a better writer and a better critical thinker,” she recalls.

She says the Honors College “set me up really well” for a career in research, teaching her skills that led her to a master’s degree in public health and later to medical school and her residency program.

An attitude of determination

After Lydia Oluloro won her case and it was assured that the family would remain in the U.S., they settled in Portland permanently. The experience strengthened the ties between the three, mainly due to Lydia’s hard work as a single mother.

One year for Christmas, when Ann Oluloro was still a young girl, she recalls receiving a toy stethoscope and a doctor’s kit. From that point on, she knew she wanted to be a doctor. “Once I set my mind to something, I accomplish it,” she says.

Tayo Oluloro recalls how her sister always made her play the role of the patient when they were growing up. “I remember being so annoyed — I was like, ‘leave me alone!’” Tayo Oluloro says. “But she would say, ‘No, no, no, I need to take care of you. I need to make sure that you're okay.’ Ann has always wanted to be a doctor. I cannot recall a time that she’d even explored anything else.”

While Ann Oluloro would practice listening to her mother's and sister’s hearts with her new present, Lydia Oluloro listened to her heart in much bigger ways. Her mom encouraged the little girl to dream big when she first expressed an interest in medicine.

In high school, Oluloro participated in several programs that began her medical career. She attended then-Madison High School in Northeast Portland, where she was heavily involved in the health services track the school offered. Her mom encouraged her to participate in summer programs to prepare her for the medical field, even if they were expensive. “My mom has been a rock and has sacrificed so much for me,” she says.

Oluloro received a Gates Millenium Scholarship – an award that would cover her tuition and expenses through undergraduate and graduate school. The only question was where she would go. Keeping up a friendly rivalry with her sister, who attended Oregon State University, Oluloro settled on the Honors College at UO for its strong science curriculum and closeness to home.

“I’ve always admired her passion about life in general. She always goes the extra mile to do things that maybe others wouldn't do,” Tayo Oluloro says. “Seeing all these things that she's doing, you just sit in amazement and say, ‘Wow, somebody that came from quite literally nothing has really made something of herself and is then using that to do better in the world.”

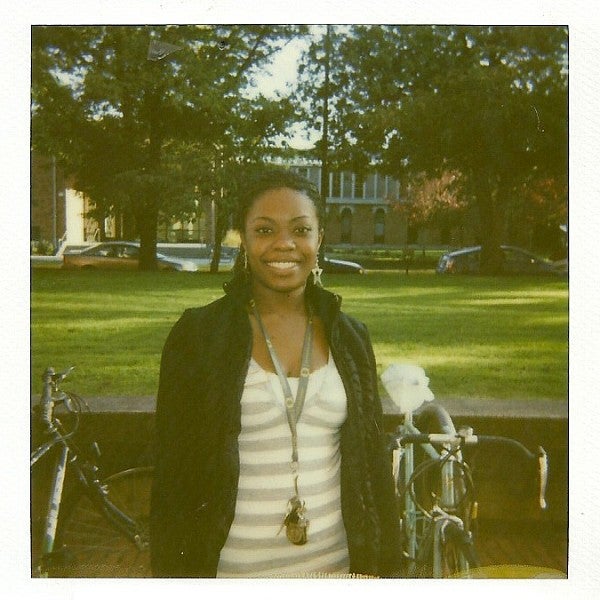

Her interest in research blossomed at the CHC, where she built skills that she would continue to use for the rest of her career. She says she remembers being grateful for the liberal arts education at the CHC and how it provided her with variety in her classes so she wasn’t limited to just science courses. She continued to participate in programs to prepare her for the medical field, such as OHSU’s Equity Research Program, designed specifically for undergraduate students.

During her time at the CHC, she went on a trip to the Dominican Republic with Outreach 360 to provide assistance for individuals with limited access to medical care.

Tayo Oluloro remembers greeting her sister when she returned from the trip and seeing how she was overcome with emotion. The people in the Dominican Republic didn’t always have access to doctors or pharmacists. “She’s always had this fire in her to right the wrongs of like healthcare disparities,” Tayo Oluloro says. “I was so touched that she was moved to tears.”

After graduation, Ann Oluloro was accepted to five different medical schools across the country, including the University of Wisconsin. She ultimately decided on Oregon Health & Science University in Portland to remain close to her mom. There, she received both her master’s of public health and her medical doctorate.

Finding and fostering her community

She remembers her time in higher education fondly but acknowledges that it wasn’t always easy for her. It can be difficult for a Black woman interested in medicine to attend a predominantly white institution. “The first thing that people notice is your skin color, your gender,” she says.

Oluloro had seen racial disparities in public health growing up, saying she didn’t meet a Black doctor until she was 24. “That’s not normal,” she says. At OHSU, she found herself the only Black woman in her cohort. She remembers looking around the lecture hall during orientation and asking herself, “Oh my God, what is going on?”

Rather than being discouraged, she found motivation in knowing that if she made it, there was no reason other Black students couldn’t achieve the same accomplishments. She got involved with the Student National Medical Association, which has a history of supporting medical students from diverse backgrounds. She also assisted in their diversity recruitment efforts at OHSU. “It’s one thing to recruit, but it’s another thing to provide support for retention,” she says.

Oluloro drew upon her experience in the Intercultural Mentoring Program Advancing Community Ties, known as IMPACT at UO, to start building the retention piece for diverse students at OHSU.

Today, Oluloro is a gynecological oncology fellow at the University of Washington. Her role involves the diagnosis and surgical management of cancers that affect the female reproductive tract. Day to day, she performs surgeries and sees patients in clinic. She describes her experience at UW as “intense, but good,” saying the faculty are supportive of her endeavors.

Oluloro’s fellowship at UW has allowed her to combine her interests in clinical trials and social epidemiology with her focus on gynecologic cancer health disparities. Her current research is focused on evaluating the multi-level challenge of enrolling Black women into gynecologic cancer clinical trials. Patients who enroll in trials tend to have better outcomes than those who don’t, but she says, “The problem is that we don’t do well with recruitment of women in racial minorities.”

She hopes that her work will be used to develop effective, culturally relevant, and evidence-based interventions to increase clinical trial enrollment of Black women; guide clinical trial investigators in study design and influence health policy. “Being able to be a researcher in that space with what I’m learning…I hope that it can be applicable to people across the board and across different races,” she says.

Oluloro works to make women’s health a more accessible and comforting space. In the male-dominated medical field, she wants to provide a voice for women who don’t always feel as if they can seriously express their concerns. “Looking at endometrial cancer, for example, the mortality rate is at least two-fold higher for Black women compared to white women,” she says. “(That) was a motivating factor for me to want to do more in the women’s health space.”

“Ann really wants to be that voice of this movement where minorities are really understanding that they can do it, that they can have a seat at the table and enter into the healthcare workspace in whatever capacity that is.”

Oluloro’s fellowship at UW will end next year. While she’s unsure where she’ll land as she enters the next step of her career, she knows she wants to continue her career in academic medicine. Whether that’s continuing to participate in fellowship programs or switching gears entirely, she is sure to conduct research that benefits those who need it most.

“As I leave this fellowship, I’ll always remember my roots,” Oluloro says, thinking of her mom. “I’ll continue serving the communities I’ve always wanted to serve.”

Her sister describes her as a role model. “Ann really wants to be that voice of this movement where minorities are really understanding that they can do it, that they can have a seat at the table and enter into the healthcare workspace in whatever capacity that is,” Tayo Oluloro says. “I think that she leaves a legacy every single place that she goes.”