Turning the page

Coffee or tea: Coffee — do you even have to ask?

A must-read book for students: Moby Dick. Or something by Thomas Pynchon. I don’t know, that’s an extremely hard question.

Favorite song right now: I’ve been playing R.E.M.’s “Cuyahoga” a lot recently. For whatever reason, I’m going back to my late high school playlist.

In May, the ground is thawed, and Casey Shoop plants a bag of sweet pea seeds in the front yard of the Portland home he shares with his partner, Gabrielle.

The seeds are his mother’s, who passed away in the spring of 2023, and Shoop – a Clark Honors College senior instructor of literature – hopes to continue the tradition of planting them every year. “My mother’s great abiding passion was gardening,” he says, reminiscing about his childhood memories growing up in Long Beach, Calif. “Every year in the front of the house, she would plant these beds of sweet peas, and they would just explode in these riots of color.”

The vines would spread down the block, he recalls, in the sandy soil. Shoop visited his childhood home last spring and gathered seeds right before his father had to sell the house.

At the CHC, Shoop’s love of books began with his mother, who was a first-grade teacher. “My mom taught people to read, so that was a deep love transfer,” he says, wistfully. Whenever they visited a bookstore together, she always bought him a book, another tradition he carries on today.

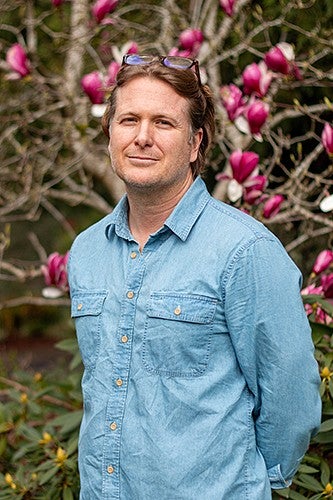

Shoop has been a core faculty member since he arrived at the Honors College in 2014, making him one of the “old guard,” as he describes his role. Students love him for his wit and endless questions, readily signing up for his courses on literature, film, and philosophy.

Outside the steady rhythm of teaching, Shoop’s personal life has changed profoundly within the past year. When his mother died, he moved his father temporarily to Oregon, and his partner developed serious health issues. He’s been working with her during her recovery process, and through his own grieving process. “I don’t think I’ll ever get out of the denial stage of grieving,” he says. “People say there are phases, but, you know…” he trails off. “My mother was a teacher, and that helps me carry on.”

A childhood for the books

Shoop remembers Long Beach fondly. His father ran an auto parts distribution business, while his mother taught. Shoop always looked up to his older brother, Joseph, especially when it came to reading. “I read all the beatniks because of Joe,” he said. “I got a rucksack and wrote poetry because of him.”

He remembers hungering for the wider world and reaching for Jack Kerouac’s “The Dharma Bums” at just the right time, or nabbing contraband books from his brother’s room.

Joe Shoop remembers the first time he read Kerouac. “I was reading all these terrible, kind of John Wick, serialized killing books,” Joe Shoop says, “and one day when we were at a bookstore, and my mom said: ‘You should try ‘On the Road.’’ I never went back to the ultraviolence after that.”

Grieving has strengthened the brothers' bond. “We talk about a lot more stuff now that we’re older,” Joe Shoop says. “We’re kind of working through grief together. It’s difficult not to be closer after something like that.”

The brothers recently promised each other to visit a new city together every year. This year, they decided on Minneapolis. Joe Shoop says it was a perfect weekend with his brother, watching basketball, popping into bookstores, attempting to have a séance with the spirit of Prince, and enjoying the Midwestern sun.

Joe Shoop also planted sweet peas in the spring. He walks a long commute to work in Berkeley and has been dropping seed pods along the way. “He’s going to Johnny Appleseed the joint,” Casey says.

Casey Shoop attended college at the University of California - Berkeley. He remembers traveling up the coast to San Francisco with his family as his father belted out lines from the pop song, “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).”

Even at a young age, Shoop thought the Berkeley campus was special. “I had some inkling of the radical history of the place that was important to me,” he says. “It mattered to me in some precognizant way. It was all there, percolating in the air.”

Highlights from his undergraduate degree include a year-long course where Shoop read the complete works of Shakespeare; taking Thom Gunn’s poetry class; and playing frisbee golf on campus late into the night.

The Shakespeare course, which was taught through a feminist psychoanalytic lens, changed how Shoop saw literature. “In college, I was so desperate to know things,” he says. “You want something to stand on, and what I wanted to stand on was all of Shakespeare. That felt really good to me. It was very important to have my eyes on every word.”

He finished with a degree in English and comparative literature. After a brief stint working for the U.S. Census Bureau to save up money, he moved to the East Coast, taking up residence in New York City as a graduate student at Columbia University.

Shoop says he struggled in graduate school—his brain wasn’t wired for endless hours at the library researching one topic. But he loved the city. “The city got in my blood immediately,” he says, and he stayed for nearly 10 years.

His days at Columbia were filled with long academic discussions and noir movie marathons. The hyperfixation and pre-professional performances of graduate school rubbed Shoop the wrong way. He grew restless. “I eventually decided I would move to South America and figure out what I wanted to do instead,” he recalls.

He set off for Argentina, books in tow, and wandered around reading until his money ran out. “Then I was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m getting paid to read books at Columbia University, what am I doing?’” he remembers. “I went down to Patagonia and looked off the end of the world, looked at huge ice, and I thought ‘maybe I should go back and finish this thing.’”

A second chapter

He finished his studies at Columbia and moved back West after being accepted into a post-doctorate program at the University of Southern California. “I think I’d probably still be in New York, reading and stringing TA jobs together if I hadn’t gotten that,” he says now.

Shoop was happy to be back near his family. “When you get to the West Coast, you’ve arrived at something of the narrative fulfillment of the United States,” he says. “Joan Didion says this, famously, and I was interested in what that was about.”

He focused on that idea in his post-doctorate work, but when he finished at USC, he was ready to leave California. “I knew a few friends from graduate school who ended up living” in Eugene, he says. “I’ve always loved the big, whispering trees.”

Shoop arrived at the Honors College in the fall of 2014 at the same time as Professor of Practice Barbara Mossberg.

Mossberg recalls that at the time, the Honors College was a loose federation of different academics. She and Shoop would meet up regularly for long, literary discussions. “We would talk about our teaching, and really got to be very close colleagues,” she says. “Casey is an incredible colleague. He grows with the knowledge he consumes.”

Shoop’s days are long. He gets up at 6 a.m. and makes a pot of coffee, and then settles into work. “My brain is best in the morning, so I try to do my most important work then,” he says.

Grading, planning classes, and searching for course material are the focus – he makes sure to keep quiet, not wanting to wake Gabrielle and her 10-year-old child. His dog, Winnie, nudges him around 9 a.m., reminding him that it’s time for her walk.

They take a few laps at a nearby park and Shoop calls his dad, then his brother. He’s been talking to his family every day after losing his mother, trying to figure out how to keep them together without the woman who served as their glue.

“I’m just gonna be in denial forever about it,” he says. “At least I have good people to talk to about that denial.”

A day in the life

On the days that Shoop is teaching, he commutes down to Eugene. He fills the nearly two-hour drive by listening to music that his students recommend, like Phoebe Bridgers or Taylor Swift. “I like to think it helps me understand them more,” he says with a laugh.

This spring, Shoop is teaching a 6 p.m. course called “How the West Was Spun: Myth and History in the American West.” The campus is nearly empty by class time, with some stragglers shuffling out of the library toward the dining hall. Despite the late hour, students sit up straight in their seats in Ansett 192, ready to discuss the most recent film they watched: “Shane.”

The late class start isn’t a problem for Robert Hawes, a CHC senior. He finds himself energized by Shoop’s classroom persona. “I don’t know many professors like this, but he’s very animated,” Hawes says. “He is very good at making the material easy to engage with, he breaks it down really well.”

“How the West Was Spun” is structured so students lead in-class discussions on the films they watch at home. Hawes enjoys hearing how his fellow classmates interpret the material. As a history major, he says he often has different takeaways than his STEM or philosophy-focused classmates.

After Shoop shows a scene to the class, they break into small discussion groups. Shoop squats down next to a table of four students, bobbing his head to their conversation. The class reconvenes, and every point that a student makes, Shoop adds to it. The lid of his Stanley thermos, filled to the brim with black coffee, rests precariously in one hand. Shoop gestures wildly with the other, trying to convey his endless passion for the movie.

“Little Joey reminds me of my father when he was young, so this film really does something for me,” he explains.

Each question that a student raises he sends right back to the class, asking what they think about it. When a student in the first row asks Shoop a pointed question, he rocks back and forth on his heels, a smile creeping onto his face. “What do you think?” he asks.