An endless passion for research

The memories of Ethan Dinh’s freshman year during the COVID-19 pandemic have mostly faded. But while he recalls the long days in his dorm room in Global Scholars Hall and rarely getting the chance to explore the University of Oregon’s campus as lowlights, the experiences opened a door for him.

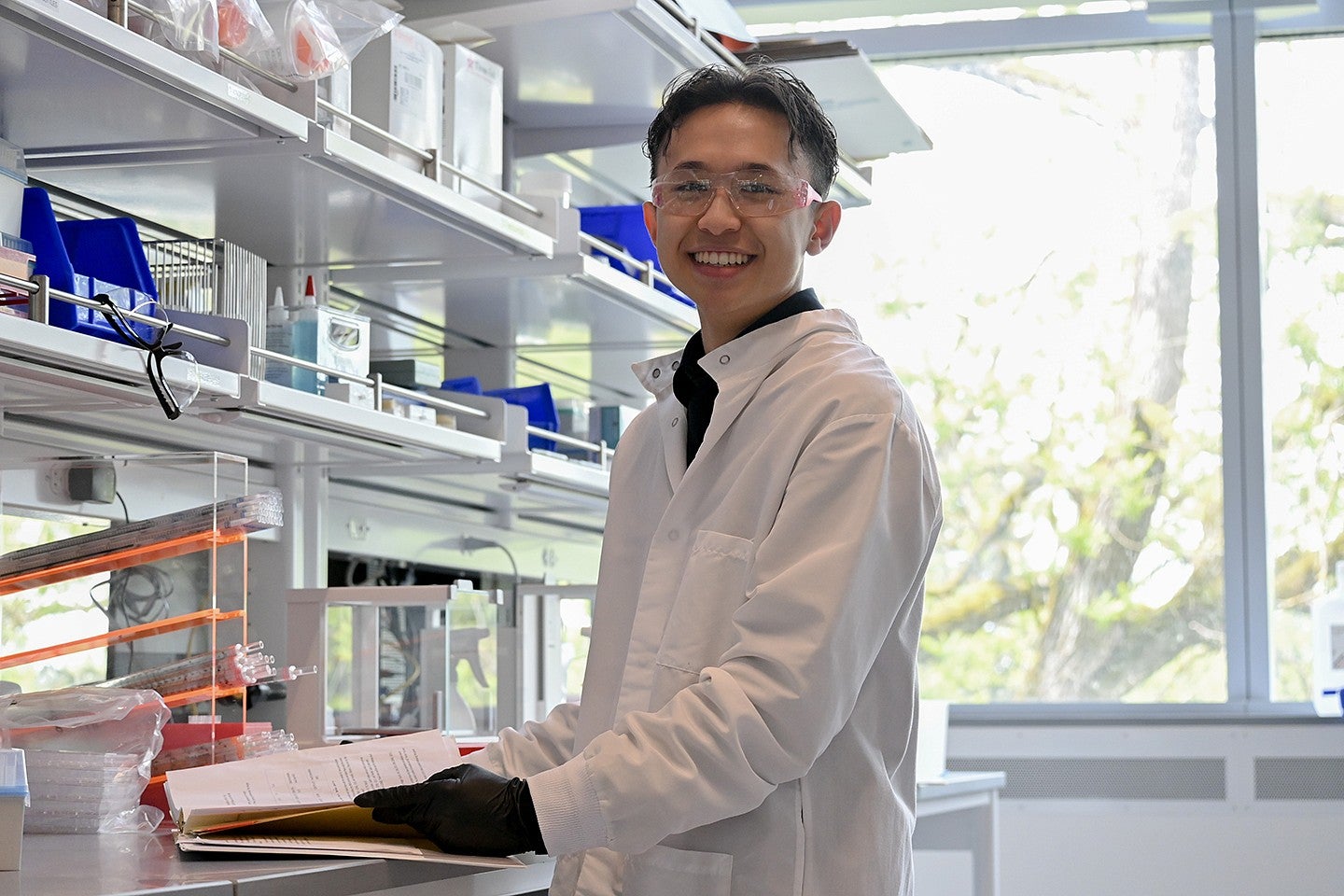

A friend who worked in one of UO’s many science labs took the time to show him around the Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact, then a complex of newly built facilities. The two walked across the empty sky bridge, and as he entered the building, he saw new microscopes, lab benches and state-of-the-art bioprinters.

“These weren’t high school labs anymore, I can tell you that much,” he recalls. “I instantly knew I wanted nothing more than to work there.”

Within days, Dinh applied to the Knight Campus Undergraduate Scholars Program because he wanted to make scientific change that could have real-life health impacts on others.

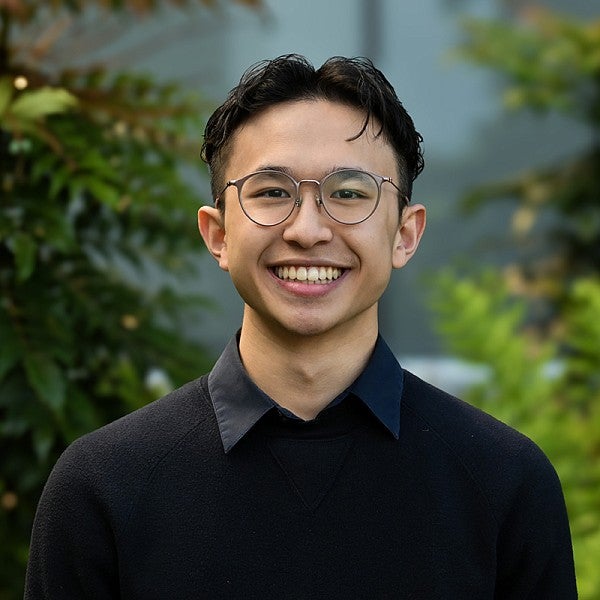

Ethan Dinh

Describe your experience at CHC: Refreshing and enriching. The small class discussions were a welcome change from the larger STEM classes I was used to. The best part was the diverse range of class topics, many of which I wouldn’t have explored if not for the CHC.

One decision that made all the difference: Applying to the Knight Campus Undergraduate Scholars Program. I vividly remember seeing the Knight Campus for the first time and feeling an instant connection.

Advice on the thesis project: Start writing early. It gives you ample time to edit and, most importantly, allows you to enjoy your senior year without the stress of last-minute writing.

Advice to incoming first-year students: Don’t hesitate to reach out to professors for opportunities. You don’t have to be a perfect student to apply for positions. Just go for it.

This summer, I can’t wait to: Spend time with my grandma. While I’ll be working in Eugene, I plan to frequently visit her in Portland.

What I’ll miss most about CHC: I’ll miss the people the most. I’ve met an incredibly supportive group of friends here.

Where I’m headed next: I plan to attend a dentistry/PhD program. During my gap year before matriculating, I’ll be working at a biotech company and the Guldberg Lab.

He was accepted into the scholars program, which kickstarted his three years of research in the Guldberg Lab where he’s studied bone reinjury. Today, Dinh is graduating with a computer science major at the Clark Honors College. He has minors in chemistry and mathematics, and plans to study dentistry after he graduates.

His Honors College experience has led him to have a more well-rounded education, he says. Dinh has enjoyed the humanities courses he’s been able to take in the CHC. “I’ve gotten to see a more human side of science,” Dinh says. “I like learning about the lives of people I’ll get to work with.”

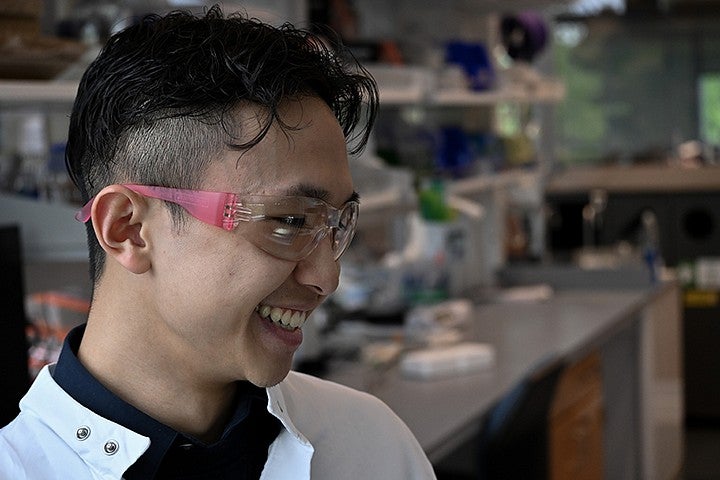

He found a mentor in Dr. Genevieve Romanowicz, a postdoctoral scholar who supervised him in the Guldberg Lab. She remembers Dinh’s approach to his first college research project fondly.

“When Ethan started, he was sometimes worried about ‘messing things up.’ But we talked about how that is often just part of the scientific process,” Romanowicz recalls. “After that, he was more fearless in his work. That’s not to say he didn’t make mistakes — he made plenty. But he always figured out what happened, why, and how to avoid it in the future.”

“If we could clone Ethan, we would.”

Dinh grew up in Happy Valley, a suburb in Clackamas County, where he was raised largely by his grandmother. He was the only child of an electrical engineer and a small business owner who worked long hours, so his grandmother would cook him dinner and build LEGOs with him.

He remembers watching and playing along with the quiz show Jeopardy! alongside his grandmother, translating the questions for her into their native Vietnamese. He didn’t speak English until kindergarten, so they both benefitted from the nightly routine: he practiced translating, and she added to her never-ending collection of fun facts. “As a team, we weren’t too bad,” he jokes.

He first discovered his passion for research in high school. In his first year at Oregon Episcopal School, a science teacher encouraged him to work on an engineering project—one that almost burned his house down.

“I built a linear induction motor and tested how temperature affected the performance of the motor,” he says. “I incorrectly chose to use a car battery as the power source. Thankfully, the only casualty was a hole in my pool table.”

His less fiery high school work caught the eyes of prestigious science groups, including the Office of Naval Research. “I was fortunate enough to both work really hard and be recognized for it,” Dinh says now. His project aimed to find a cheaper and more efficient way to remove salt from water, and he used a grant-funded filter and low voltage to do so.

Once he got to UO and the Honors College, Dinh went all in on his research. His first project with Romanowicz was bioprinting injectable bone-like microdots to treat bone reinjury, potentially removing the need for expensive bone grafts.

“Ethan gets focused and has a lot of hustle when he is doing bioprinting in the lab,” Romanowicz says. “It’s so fun to see him shuffling around the lab between the robot printer and the cell culture room like it’s a coordinated dance to get the timing right for his bioprints.”

Robert Guldberg is the executive director of the Knight Campus and the head of the lab where Dinh worked. He was drawn to hire Dinh not only because of his stellar academic record, but also his past dedication to his research projects.

“Ethan is clearly very smart, but it is his curiosity to learn new things and work ethic that really make him special,” Guldberg says. “If we could clone Ethan, we would.”

Excelling at the CHC and beyond

Though Dinh has worked on more than 10 research projects throughout his time at UO, his favorite has been his CHC thesis, “Proteomic Signatures of Tibial Bone Stress Reinjury,” for which he won the CHC’s Scientific Frontiers Award.

Through collaborative research with Massachusetts General Hospital, Dinh studied roughly 1,500 serum proteins in 30 female recreational runners. He mapped these serum proteins to locate where reinjury would be most likely, which he says could serve as a powerful preventative tool.

In April, Dinh competed in the second-annual CHC Three Minute Thesis Competition, where students presented a three-minute speech about their thesis projects with one slide to explain the significance. He placed first out of 10 finalists and took home a $750 cash prize.

“It was nice to practice my thesis defense before the actual day came,” Dinh says. He successfully defended his thesis in the conference room of the Guldberg Lab, and his three-minute version was a reassuring memory when he got nervous.

Life after college

Dinh says being involved in medicine has always been a dream, as he spent most of his childhood imagining himself becoming a doctor.

Today, though, he has hopes of attending dentistry school in the fall. Last year, Dinh did a volunteer shadow experience with a local dentistry group and fell in love with the profession.

He sees the most important part of medicine being the interaction with patients. “The way you navigate the boundaries of respect is something that I really, really enjoy,” he says. “I would love to meet and catch up with patients, just like my dentist did. She watched me grow up.”

While working as a dentist, he hopes to spend a significant amount of time researching his passions of machine learning and computational biology.

After collaborating with Dinh for three years, Guldberg says he is “one hundred percent confident that (Ethan) will achieve great success no matter his future career journey.”

Dinh often saw his grandmother in the patients he worked with during his shadow experience. The slower, older patients — who often didn’t enjoy going to the dentist — would sometimes leave with a smile, rather than the scowl that they came in with.

He credits the dentists and assistants with those transformations, saying their level of patient care and empathy was unmatched. Seeing that kindness drives him to be a more compassionate healthcare worker in the future.

“I hope I’ll become someone she (my grandmother) can be proud of,” he says. “Both in my career and as a person.”