Working for the community

Madeline Thomason remembers the time she shadowed a friend of her mother’s who worked as a doctor at an urgent care facility. The smell of antiseptic and the echo of coughing patients swirled around Thomason, who wanted to explore her interests in biology and the medical field.

She spent most of her time helping the doctor with the final notes on patients, getting them water when they needed it, and observing.

At one point, a five-year-old arrived with a split-open forehead and needed stitches. Thomason watched as the boy took the stitches like a champ. His mother, though, wasn’t so lucky. She nearly fainted, but Thomason instinctively reached out, caught her, and lowered her into a chair.

“After that day, I knew I wanted to go into medicine,” she recalls. “As I’ve gone further down that path, the decision became more and more clear to me that I want to learn about how humans work.”

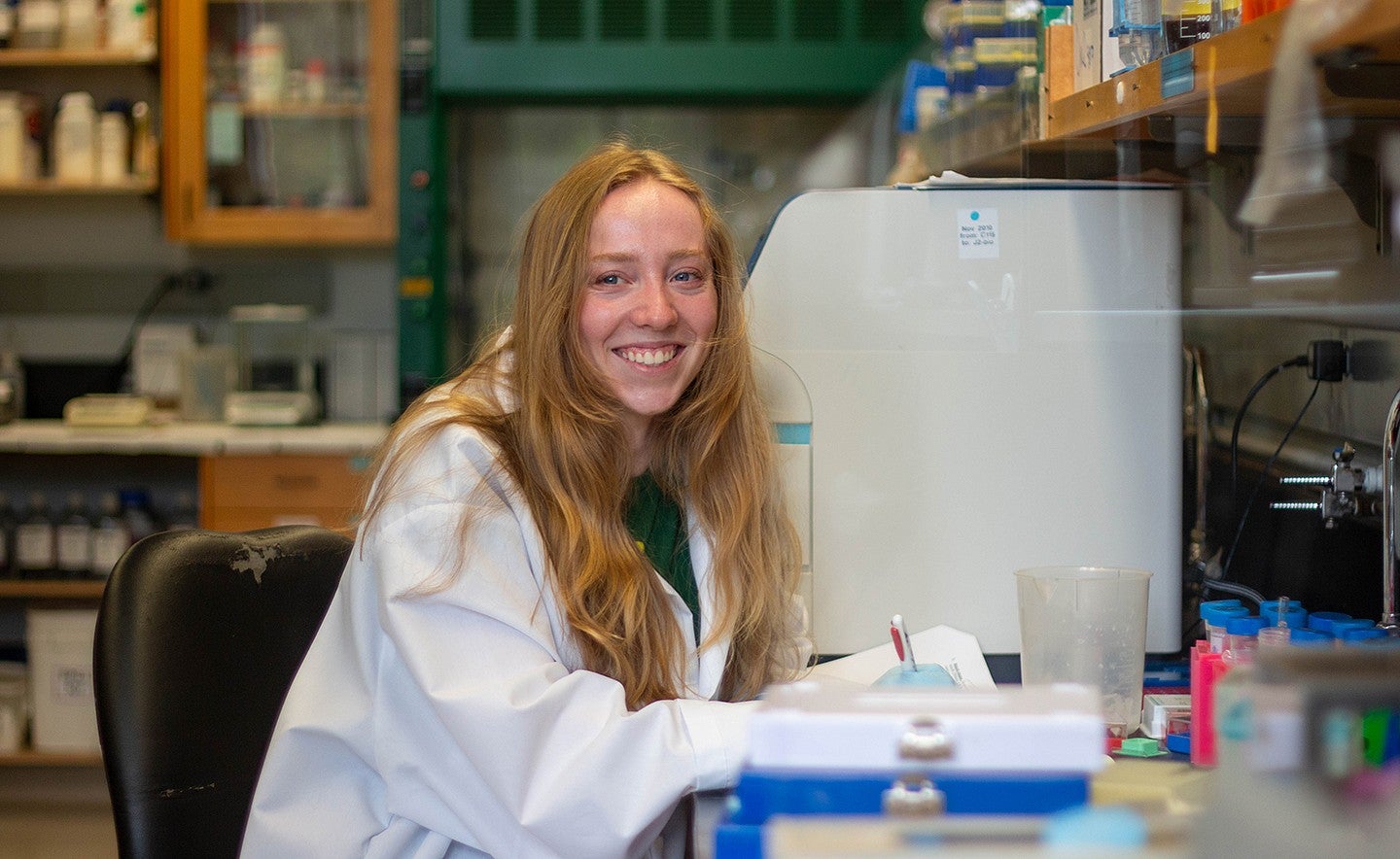

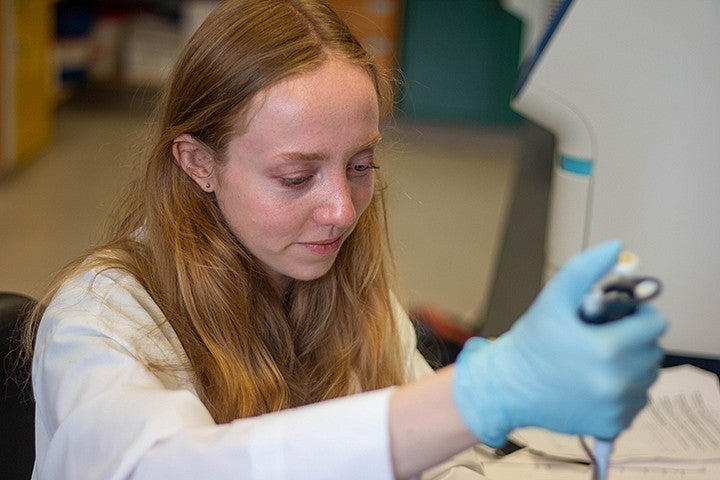

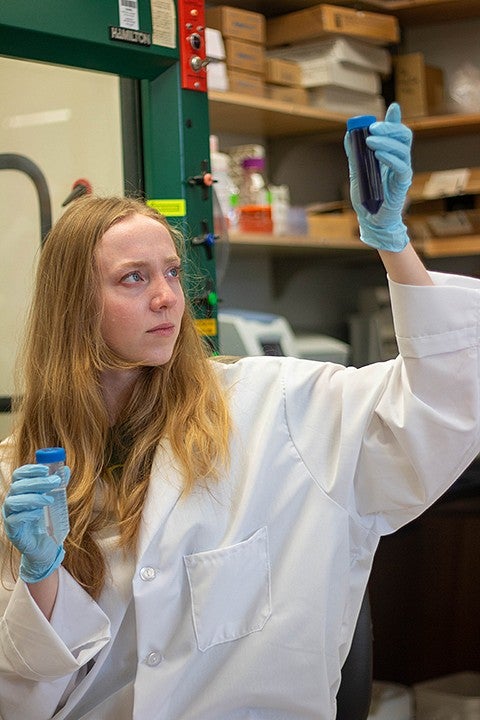

At the Clark Honors College, Thomason majored in biology and had minors in chemistry and Spanish. The Stankunas Lab at UO provided a unique training ground for her to learn about the regenerative properties of the zebrafish. And in her free time, Thomason served as the team captain (“team mom,” as she puts it) of an intramural soccer team.

Madeline Thomason

Major: Biology

Minors: Chemistry and Spanish

Thesis: “Exploring the Role of Actinotrichia During Fin Regeneration”

Describe your experience at CHC in a few words: Interesting, eye-opening, fun

Advice to incoming first-year students: Take classes that you’re interested in beyond your major

What I’ll miss most about the CHC: Stability

I’m grateful for: My family

Where I’m headed next: Eugene Pediatric Associates to work as a medical scribe

Song on repeat: “Saturn” by SZA

Favorite class taken at the CHC: “Black Literature, Science, and Reproductive Justice” with Angela Rovak

Her senior thesis, “Exploring the Role of Actinotrichia During Regeneration,” studies the relationship between actinotrichia – collagen-based fibrils that help guide bone formation – and a group of niche, bone-promoting cells. Her work impressed her mentors and others in the Stankunas Lab and Thomason came away feeling further accepted.

“One of my favorite things about my lab is how equal everyone feels,” she says of the experience. “My thoughts and opinions matter, and everyone is genuinely happy that I am there. My role initially in the lab was to learn from others, and that role slowly transitioned into learning on my own through experiments.”

Paying attention to the details

Thomason grew up in Beaverton, the older of two children of Mary and Alex Thomason. As a child, Madeline Thomason always paid attention to the details of what went on around her.

Mary Thomason remembers when the family went to a restaurant for a gathering with her nearly three-year-old daughter in tow. The little girl’s grandmother said she needed a refill on her drink and Madeline looked up from her high chair and exclaimed: “Dan will bring it!”

“We looked around the table and said, ‘Who is Dan?’ When our waiter returned, we saw his name tag said ‘Dan,’” Mary Thomason recalls. “He had introduced himself at the start of the evening and Madeline had remembered.”

Being a detail-oriented person played out in her life as she got older. She attended the International School of Beaverton and thought about going into architecture. “It seemed like a blend of art and science,” she remembers thinking.

After shadowing both an architect and then the doctor in high school, Thomason realized the extent to which she wanted to work closely with people. “I like how doctors build relationships and trust with their patients,” Thomason says. “The better you know your patient, the better you can care for them. I think it’s profound how much trust and effort that takes.”

And it’s not an overstatement to say that her family has a strong tie to the medical field. Her mother is a general practitioner, her aunt is a radiologist, and a cousin she is close to has started school at Ohio State University to become a dentist.

“Being part of a ‘legacy’ of doctors has helped me get comfortable with using medical terms and with aspects of my body that may have otherwise made me feel ashamed,” Thomason says. “My family has a lot of trust in science and medicine, and places a lot of value on these professions. I think the ‘family legacy’ of being a doctor mostly helped me to gain a lot of respect for the profession.”

Ties to the community

Thomason’s original idea was to attend Washington University in St. Louis. But the pandemic sidelined those plans. “Suddenly, the world was kind of scary,” Thomason recalls. “A lot of people were sick and dying, and traveling across the country to Missouri did not seem as safe or fun anymore.”

She chose to study at the CHC and has no regrets. “Even though I knew for sure I wanted to go into the medical field, I wanted my college education to be broader than that and the CHC provided that broadness,” she says.

As a junior, Thomason took “Black Literature, Science, and Reproductive Justice” with Angela Rovak, CHC’s faculty director of first-year experience and a literature instructor. The class discussed how Black women in particular receive disproportionate misdiagnoses and mistreatment in the medical field when compared to White women.

As pandemic shots rolled out publicly in late 2020, Thomson noticed anti-vaccine rhetoric in political and social spheres. “I think it’s important for doctors to understand the baggage and reasons why communities of color don’t trust the medical field,” she says. “It’s their job to come to people from a place of understanding and kindness and validation, rather than judgment.”

She also says doctors and others in the medical field have a higher level of responsibility to cut through disinformation. “COVID made me see the interaction between medicine and politics that was not obvious to me before,” she says.

After graduation, Thomason will start a job as a medical scribe, working for Eugene Pediatric Associates. She made the connection with one of the doctors there – Dr. Pilar Bradshaw, who spoke to Thomason’s medical physiology class during her junior year.

At the time, Thomason introduced herself after class and Bradshaw encouraged her to stay in touch. Thomason followed up with her two months ago and she got the job. After she gets some experience, Thomason plans to apply to Oregon Health & Science University for medical school—where both her mother and aunt went.

“I really believe in having breadth to your knowledge,” Thomason says. “My time at CHC, in the Stankunas lab, playing sports and being with my friends all helped me see myself and others as more than a summation of parts and will help me treat people holistically as a doctor.”