The Ampersand Agent

CHC Class of: 2003

Coffee or tea: Coffee in the mornings, but I switch to peppermint tea in the afternoons.

What are you reading right now: Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series

Walk-up song: “Spitting Off the Edge of the World” by the Yeah Yeah Yeahs

Favorite CHC memory: Visiting the Honors Library in high school, I remember seeing the bright, airy space with all the plants— it felt like home.

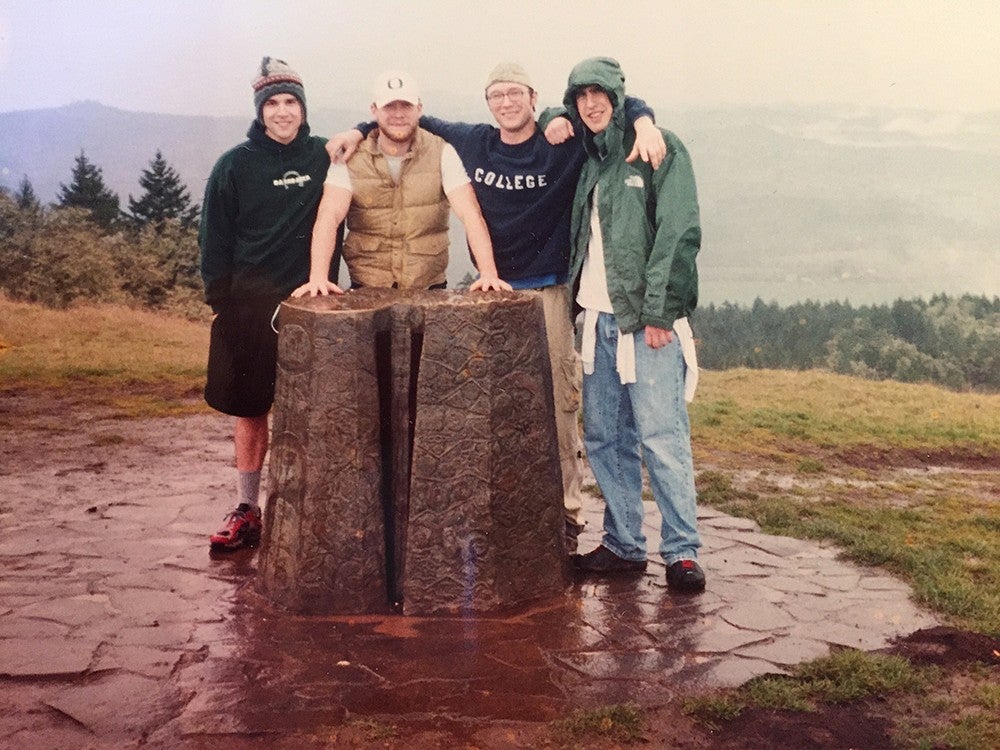

Joel Weber remembers the moment he received the final push to move to New York City. A recent Clark Honors College and journalism graduate who had defended his thesis in the fall of 2003, he was saving money for the next phase of his life, though he hadn’t yet decided where to go.

New York offered promising opportunities, but moving across the country was daunting, considering Weber had never lived anywhere other than Oregon. Encouragement from a journalism mentor echoed in his head: “For the thing that you want to do, you should go to New York,” he remembers being told.

Still living in Eugene, Weber deliberated the move until a push from the universe helped him make the decision. On a windy winter night, a broken tree branch fell 30 feet and landed on his car. It was totaled. “That was sort of the little push that I needed to get me over the hump of ‘do I want to do this or not?’” he recalls.

With a check from his insurance company, Weber moved to New York, comforted that subways would replace his need for a car. “I’m going to give myself two years,” he told himself. That two years turned into five. “I got to five, and then I was hooked,” he says now.

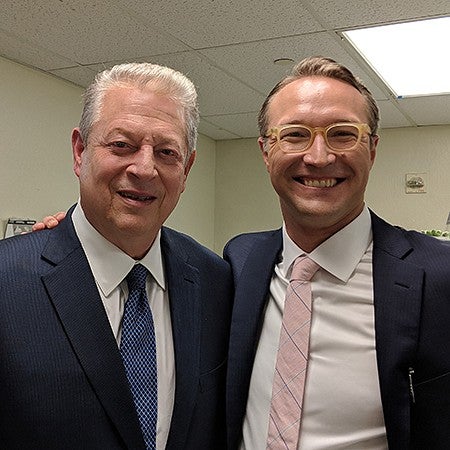

His knack for following opportunity is characteristic of his approach to journalism, channeling possibility where others might freeze at obstacles. Since graduation, he’s held prominent roles at Men’s Health, ESPN Magazine and now Bloomberg, where he is an editor and leads Bloomberg Explains.

Weber grew up in Hillsboro, Oregon, and attended Glencoe High School, where his outgoing nature helped him earn leadership positions. “I was always in a place where I was looking to lift other people up around me,” he says, noting that he was editor of the school paper and a co-captain of the basketball team.

His wife, Laurel Pinson, was struck by his gregariousness from the first time she met him in New York City. “Student body president is how he read even when I met him for the first time,” she says.

His journalism efforts in high school earned him a Columbia Scholastic Press Association Scholastic Gold Circle Award in 2000 in the category of personality profile. The award catalyzed his interest in the field and motivated him to take journalism classes alongside the Honors College curriculum at UO.

“I just really liked that combo,” he says now.

Between participation in the Walter and Nancy Kidd Creative Writing Workshops and his contributions to FLUX, a student-run magazine in the School of Journalism in Communication (see the 2003 edition here), Weber was well-prepared to launch his career by the time he graduated.

“People come to New York and their New York story is all about how they change paths 16 times,” Pinson says. “He’s one of the only people I know who knew what he wanted to be and has made it their calling.”

After several years of magazine writing in New York, Weber got a job at Bloomberg where he has been since 2012. He says he makes it a habit to learn as much as he can about his colleagues because it helps to create effective teams.

“He doesn’t make small talk,” Pinson says. “He’s not going to ask you about the weather. He’ll find out something unique and strange that you both have in common and then learn a million things about it.”

Weber refers to himself as an “ampersand agent,” taking on the role of creating teams of people who might not otherwise work together. Bloomberg is a global newsroom that employs more than 2,000 journalists. He refers to the company as a “superpower.”

His leadership qualities in interpersonal interaction translate to skillful storytelling. The CHC Post interviewed Weber to learn more about his approach to the job he loves, his team-centric leadership style, and how the Honors College played a role in shaping his future.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

What hooked you about New York City?

New York is an addiction— that’s it. It's taken me a while to confess to that, but I do think not everyone can live here, and I’ve watched that happen. For New Yorkers, it also feels like you couldn’t live anywhere else. And I probably am closer to that at this point.

I think of New York like a flower. It’s so big and stuff is always happening. There are new neighborhoods to go check out, and it just feels like the flower is opening, but just for you. That becomes like this magical symbiotic relationship, where it feels like the city is giving you things, but you’re giving the city something. It feels really magical.

What drew you to your profession?

The thing that continues to speak to me about it is storytelling, and one of the things that I saw, even at the time, was that if you approach journalism to tell you what happened yesterday, that was already becoming a tougher and tougher story. Newspapers, you know, we’ve all witnessed that they were once pinnacle business models and created enormous amounts of wealth, and then the internet effectively upended that business model. So, in addition to being a storyteller, I’ve always tried to have a business hat on.

One of the things that has been really interesting about magazines, which I’ve spent most of my career in, is that it’s really about stories, and you have an audience you’re trying to reach with the type of story. It was a love of the medium, and I still have a great affinity for it. I think the amazing thing about a magazine is that it’s not quite a book but also not a blog post. There’s a space in the middle.

We’re in a war for people’s time, and you are constantly asking someone, somewhere in the world, to spend time with you. You have to consider if that’s a worthy invitation. The content we make really matters, and we have to distinguish our work as journalists from all the other noise in the world. Hopefully, we can touch people and the stories can move them or illuminate something that they might not have fully understood or provide a greater understanding about.

A deeper understanding is something that I always gain from reading magazine stories. It's nice to hear that you're considering it in your own work as well.

I come from the tradition that everything you put on the page matters, and you are trying to get a reader to spend time with you and really appreciate the craft that you put into it. I think in general, there’s a craft that is missing in a lot of the world. Finding places that you can bring your craft and bring it to bear no matter what you’re working on is important.

How do you leave a mark that is unique to you, something that only you are capable of doing? Honestly, that is a place where the Honors College has profound resonance because you can think about things more holistically while the world is trying to put us in tighter and tighter lanes rather than teach us to think outside those boxes.

Did that contribute to the way you continued to think about things as you went into your career? What did you take away from your time at the Honors College?

One of the things that’s surprising when you start working in big companies is that there are a lot of people, and they work in silos sometimes. One of the things that I've learned to do is be what I call an ampersand agent. Essentially, exploring how you get people who might not otherwise work together to work together. A big company has all kinds of potential, but people are assigned to teams that might not always have the same agendas.

When you can get people to work together to do something that may be outside of their job description, it benefits morale. I was able to do some of those essential things because of my Honors College style of thinking; where you’re informed a little bit about a lot of things. And then the journalist part of you is always asking questions.

It's so intertwined with being a journalist as well; taking classes on all those different topics and learning all these different methods of thinking lends to being able to talk to people about their specialty.

Yes, I think that a love of learning is an essential thing. I know there are things I do not know anything about, and I’m humble enough to admit that. But I can also ask questions of people who know about them and become smarter in the process. In journalism, I would say I’m a generalist. Other people have way more interesting skill sets and are dedicated to one specific area of coverage. If anything, where journalism has gone has been away from that generalist approach toward more of a narrow and deep approach. That’s reflected in Substack, for example. I’ve always tried to kind of transcend specific beats in that way.

What was your thesis on at the CHC?

I was in the Kidd Creative Writing Tutorial. I did it my senior year, and so I used that as a way of writing my thesis. It was a collection of creative nonfiction stories — I changed it a couple of times — but it related to my parent's divorce. It was a way of doing creative nonfiction stories that were memoir-adjacent.

“How do you leave your mark that is unique to you, something that only you are capable of doing? Honestly, that is a place where the Honors College has profound resonance because you can think about things more holistically while the world is trying to put us in tighter and tighter lanes rather than teach us to think outside those boxes.”

You mentioned earlier that something you’re always thinking about in your journalism is the business side of things. Maybe that’s just the nature of having been at Bloomberg for five years, but where would you say that came from?

I think I learned it as the industry has changed. They don’t necessarily teach you about the business of journalism, but becoming a professional — it becomes part of what you’re learning. Much of it has been working in an industry as that industry has evolved for 20 years. We had a very lucrative business model that was upended by the internet. But the thing that we never really talked about was how the advertising worked into everything. Advertising was the business model. Where we are now, advertising is maybe a small part, but we’ve become much more of a subscriber-centric industry.

What kinds of leadership roles do you take on in the workplace?

When you first start in the industry, you look for opportunities, spot opportunities, see others, watch others have opportunities, and learn from them. And then you get a moment in time where you have your own opportunity, and you know what to do when you’re in those moments. Or, it feels like you’ve been trained for that moment, so it doesn’t feel foreign when you find yourself in that spot. You learn how not to do things, too.

What’s next for you in your current role as the head of Bloomberg Explains?

II pitched basically what I call a triangle offense. Explainers, service, and games are part of that, and it’s still in the early days, but the team has grown for a year into the role. We have about 10 people now, and we just launched Pointed, our first foray into what the game space could look like for Bloomberg. We’re always asking, “How do we do this? Who do we get to work together on it? What does that editorial plan look like? How do you create something from nothing?” It’s a fun problem to try and solve.

I’m constantly considering how we do things unique to Bloomberg and distinguish our product in the wider world while also acknowledging that the journalism world is evolving at velocity.