Raising the standard

Favorite thing to do when you're not teaching: Spend time with my two children

Coffee or Tea: COFFEE

Favorite place to visit in Oregon: Anywhere and everywhere

One piece of advice for students: Find your passions in life and figure out how to turn those into a meaningful and productive career.

Song on repeat: Anything by Lady Gaga

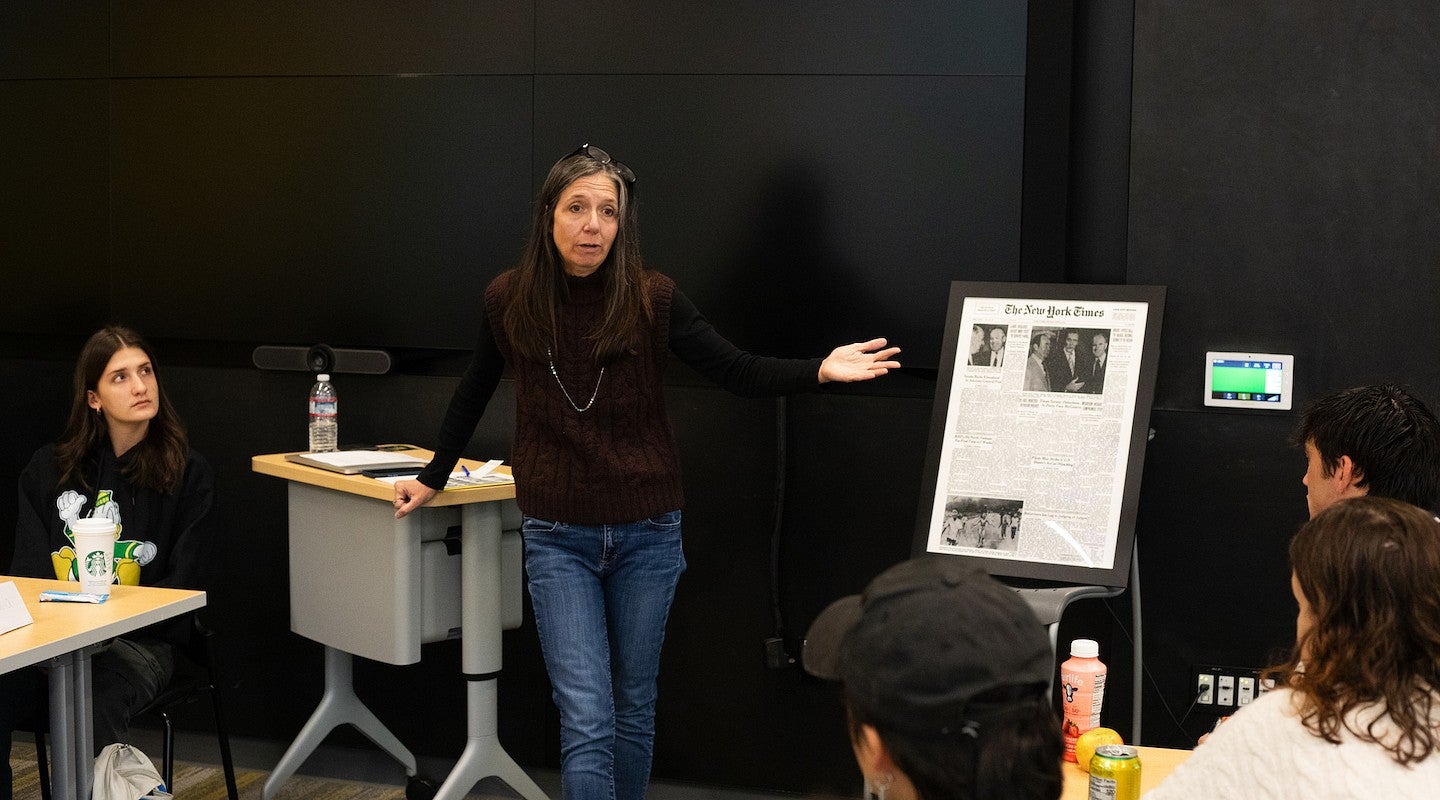

On the first day of Nicole Dahmen’s fall course about media theory and research, she passes out index cards to each student. She asks them to write “research” on one side. On the other, they list out every word that they associate with the term.

“I know research might sound like a dry, boring word,” she says. “But research is actually very dynamic and exciting – it’s an attempt to discover something. Research what you’re passionate about.”

Students are naturally inquisitive, she says. Research is a way for them to answer their questions. She knows, because she’s spent the last 20 years doing just that – through research, she investigates how journalism and the mass media can better serve society. She’s especially interested in media ethics and productive approaches to reporting with communities.

Dahmen is a longtime professor in the UO School of Journalism and Communication and a new member of the Clark Honors College core faculty.

“The students really know a lot about the media,” Dahmen says. “They have to, survival-wise.”

Media are everywhere and come in all sorts of forms – news, advertising, music, video games, and more. More important than its format, however, is the message, says Dahmen. Media can inform, entertain, or persuade. Sometimes, those messages even overlap, which can raise ethical concerns.

Her research into mass communications has illustrated just how essential it is to bring media literacy to the classroom, both at a K-12 and college level. She’s eager to share her work with Honors College students from a range of disciplines and help them be critical consumers of the mass media and deepen their relationship with academia.

Honors programs help students nurture their relationship with learning, she explains. At the SOJC, she directed the school’s honors program. She helped students develop a passion for research, some of whom went on to present their papers at international conferences. “I’m excited to bring that experience to honors students across campus,” she says.

Evolving with the medium

Dahmen’s own love of learning began at a young age. In her hometown of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, she would line up her stuffed animals and play teacher. Even back then, she was making up seating charts and grading assignments.

She’d grown up near Louisiana State University, immersed in a “vibrant academic community,” she says. Both her father and grandmother worked in design and technology. So, when the time came to experience college life for herself, she took what she’d learned from them and pursued a major in design.

Dahmen’s career started in drafting and design. But changes in technology ushered in a new era around media and she altered her focus.

“I loved the intellectual stimulation,” she says. At LSU, she seized the opportunity to explore a variety of subjects, including philosophy and women’s studies.

She worked in design for five years after she graduated in 1997, drafting machine parts and coming up with layouts for brochures. As the world moved from print to digital, Dahmen witnessed the field change before her eyes. The evolution she saw drove her interest in multimedia communication.

She always had graduate school in the back of her mind, and she returned to LSU for her master’s degree, this time to study nonprofit communications. The plan was to return to the professional field, but the love for research she developed during her studies took her in a new direction.

A professor spoke to one of her classes about a project he was working on about the photos of the 1969 moon landing. Dahmen expressed her fascination with the idea, and they invited her to be a co-author on the paper.

The study examined the so-called visual “evidence” that the landing had been fabricated. The project, she says, was ahead of its time with its investigation into visual misinformation.

It was the first of many papers she’s published in her career. She continued her education at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, where she got her doctorate degree. Working in academia allowed her to continue learning about the world through her research. Equally appealing to Dahmen, however, was the opportunity to teach.

“The mass media are one of the most powerful and influential institutions in our society,” she says. “And they do a lot of things that, quite frankly, are manipulative and unethical.”

She’s seen its reach in her own life, with ads on social media preying on anxieties about saving enough for retirement and news feeds supplementing one tragic story for another. That’s why it’s so important to help her students break down the messages they see, she says.

She wants her students to understand “that we have control over our relationship with the mass media.”

Beyond reporting the problems

She made the move to the University of Oregon in 2014. She’d had her eye on the Pacific Northwest for a while, she says, and admired UO as a leading research university. So, when a position opened up at the SOJC, she jumped at the opportunity.

Now, she spends her time teaching and pursuing new studies of her own. Currently, she’s working toward an MFA in creative nonfiction at Pacific University.

A mother of two, she advocates for media literacy in both her personal and professional life. Between family trips out to Oregon’s natural landmarks and playing with the family cat, she’s sure to set aside time to talk to her children about how they interact with the media – and how it makes them feel.

Dahmen has played a major part in many influential SOJC programs. She’s co-coordinated the Charles Snowden Program for Excellence in Journalism, which gives students the opportunity to intern in professional newsrooms and work side-by-side with journalists.

In 2016, she launched the Catalyst Journalism Project with two of her UO colleagues. Catalyst utilizes “solutions journalism” to offer a new path for reporters.

“In the past 10 years, I’ve done a lot of work on very difficult topics,” she says. She’s looked at how the news covers topics like gun violence, police brutality, homelessness – all to see how these issues can be covered “in a way that advances the conversations and doesn’t cause further harm.”

The concept of solutions journalism popped up time and again in her research: the idea that a story shouldn’t just cover a problem, but instead should also showcase the work being done to approach it.

“It’s a progressive approach to journalism,” she says. “As someone who spends a lot of time with the next generation, I like to teach a more proactive approach.”

To her, it’s not only about teaching future journalists a way to tell more ethical stories. It’s also a way to help students realize that “there are good things going well in our world.”

This fall at the CHC, Dahmen is teaching “Media (Un)filtered: Media Ethics and Literacy.” In winter, she’ll bring her work with solutions journalism to the classroom with a colloquium course called “Solutions to Our Wicked Problems.” In spring, she’ll teach a creative nonfiction research and writing course.

“Mass media touches every aspect of our lives,” she says. “There’s no academic major on campus that doesn’t need a good understanding of the mass media.”