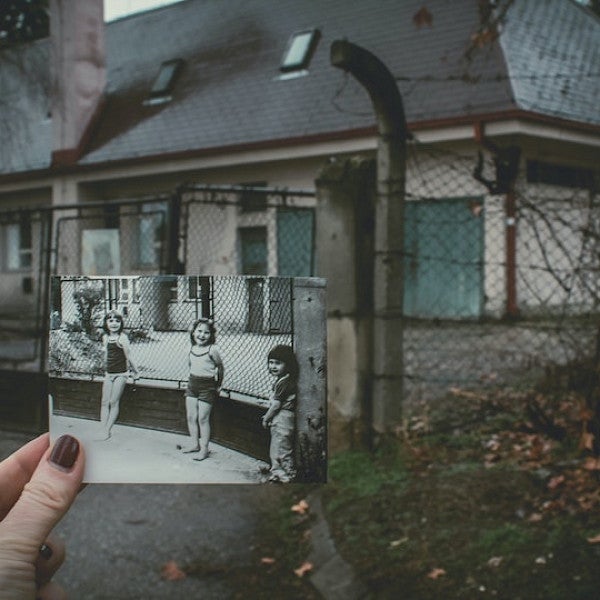

Anita Janokovic, Unsplash

Story by Claire Warner, CHC Communications

Senior Instructor of Psychology Nicole Dudukovic and her older sister were having dinner at a restaurant in Vienna when a nearby couple told them that two planes had flown into the World Trade Towers on Sept. 11, 2001. Dudukovic told her sister to write down the details of that moment, including what they had to eat, what the couple looked like, and how much the meal cost. She knew that her experience was an example of the infamous psychological concept of “flashbulb memory.”

A flashbulb memory is “a really vivid memory of when a specific event happened and what you were doing and saying at the time,” Dudukovic says. However, research suggests that just like a normal memory, flashbulb memories fade over time. “This idea of the flashbulb is that everything would be preserved like a photo, perfectly, so you would remember all of these details, and it’s just not really the case.”

Nicole Dudukovic

Dudukovic keeps the notes her sister jotted down in a box in her basement closet. Within a few years after their trip, Dudukovic used the notes to test her sister on what she recalled from their flashbulb moment. Unsurprisingly, her sister forgot several details. Even Dudukovic has a hard time recalling the day’s events.

“I can remember certain things,” Dudukovic adds. “I know I was in Vienna, I know we were at a restaurant—I want to say it was a French restaurant, which seems kind of weird. Why were we at a French restaurant in Vienna?”

Many of Dudukovic’s classes on learning and memory involve a discussion of flashbulb memories. She is fascinated by questions of how memories can change over time and why two individuals may remember the same event differently.

She also incorporates her knowledge of memory into her classroom by encouraging students to use active study methods that research suggests are more effective tools of memorization than common, less-engaged habits like rereading notes and studying with distractions.

“If you are working in groups to try to answer questions based on the reading or based on things you’ve been discussing, then you’re drawing on your knowledge rather than just reading something and writing straight from what you’re reading.”

She does demonstrations of active learning techniques in class as well, in which she presents a list of words and shows students how much more they can remember when they use an active study strategy compared with simply rereading the list.

Dudukovic knew she wanted to be a teacher when she was in high school because she loved school and learning. In grad school, Dudukovic found that although she was an introverted and often quiet student, she enjoyed leading classes and discussions, solidifying her teaching desire.

“It seemed very cool that you could have a job where you’re not only continuing to learn yourself but you’re kind of giving back,” Dudukovic says. “I had some great teachers, great professors, and felt like I could show that same interest in some of my students and help mentor them and maybe do some of the same things in the classroom that they did that made such a big impact on me.”

However, Dudukovic “had an identity crisis” shortly after getting her Ph.D. in psychology from Stanford. She briefly explored science writing and management consulting because she thought if she became a professor, she would have to mentor graduate students.

“I knew I really liked working with undergrads but I wasn’t as sure that I wanted to work with grad students and postdocs, in part because I feel like there’s so much more pressure there, that they’re getting ready to start their careers and you have to make sure that they’re going to be successful at that.”

She ultimately decided to pursue academia but focus on undergraduate education. She lectured at Stanford and became an assistant professor at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut a few years later. At the time, she described it as her “dream job” because it was a small liberal arts college where she could teach small classes, do research and only work with undergrads.

Family circumstances and being part of a dual-career academic couple took Dudukovic to NYU for three years before she joined the UO psychology department and became director of the neuroscience major, which officially launched this fall term. She was one of three professors who worked to develop the major, which draws on classes from the biology, psychology and human physiology departments. Although she was reluctant to take on a new role while juggling all her current responsibilities during the pandemic, she ultimately accepted the offer. She says she hoped to address problems of underrepresentation by taking on the position herself.

“Women are underrepresented in the sciences and in science leadership positions,” Dudukovic says. “I thought having a woman direct the neuroscience major would be good for other women to see, particularly prospective neuroscience majors.”

Before developing the neuroscience major, she started teaching in Clark Honors College in fall 2018. Back in a liberal arts environment, Dudukovic likes her new role due to the CHC’s small class sizes, undergraduate focus, and the resources that come with a large research university.

“It’s kind of the best of both worlds,” Dudukovic adds. “I feel like I’ve found my home again.”