When Dr. Marc Arsell Robinson began teaching African American history in 2009, many students entering his classes thought conversations about race in America were over.

To Robinson, this signaled a larger shift in the population about how race impacts American culture. The election of Barack Obama, he says, led many to believe racial discrimination in the United States had ended – a sentiment Robinson found himself challenging in his classes.

He later watched as a series of events – the election of Donald Trump; increased violence against Black Americans; and the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police – shifted public opinion on race once again.

“There was no longer a need for me to convince students that this history still matters,” Robinson says. Students came to class much more aware of the work that needed to be done in the United States and the world.

At the University of Oregon, the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 spurred Clark Honors College administrators, faculty and staff to discuss ways students could further their understanding of race and current events. The dialogue resulted in the creation of the Visiting Fellowship in Equity, Justice and Inclusion, where selected fellows would offer remote coursework on the Black experience in the United States.

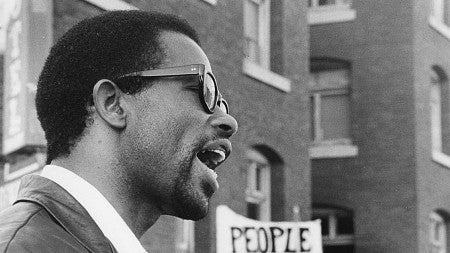

Robinson was one of three chosen initially for the fellowship. With a Ph.D. in American Studies from Washington State University, he teaches African American and U.S. History at California State University, San Bernardino.

Acting CHC Dean Carol Stabile says Robinson demonstrated incredible skill as a teacher during the pandemic, taking great strides to revise and adapt his classes to a remote environment. Also, his unique research on African American history in the Pacific Northwest set him apart.

For Fall 2022, Robinson is teaching his course, Black Panthers in the Pacific Northwest at CHC.

The course’s topic is meant to start a conversation, he says. Robinson’s research on the Black Panther Party has shown it has long been a complex organization. “Whether you hate them or love them, most people have heard of them,” he says.

Students in his class likely knew of the Black Panthers before their first session, but Robinson hopes that what they learn in the class will inspire them to add to that picture or transform it altogether.

He is working with students to tease out the Black Panthers’ complexities. The course discusses the Panther’s use of arms and their confrontations with police brutality, as well as the services they provided to Black communities throughout their history. He also plans to delve into lesser discussed aspects, like the role of women and the interracial cooperation the Panthers had with other organizations.

Robinson has enjoyed history since middle school, but it wasn’t until college that he decided to study African American history. After growing up in Seattle, he decided to focus his efforts on the Pacific Northwest – a region rarely mentioned in discussions of the Black Power movement.

His love of learning drives his teaching. For him, the classroom is a place to advance his own understanding through sharing the topic with others. The CHC encourages incoming fellows to “think about the classroom as a laboratory for conversations and ideas” for their research, Stabile says.

His course with the Clark Honors College is helping a new group of students gain a better understanding of African American history. He says he has been eager to teach in a new environment like the Honors College where students have a range of academic focuses.

“I feel a sense of responsibility,” he says. After learning about the untold history of the Black Panthers in the Pacific Northwest, he wants to give his students the chance to do the same. “I should pay it forward by offering to teach it to others who are interested.”

Against the backdrop of continued protests against racism in America, Robinson stresses the importance of understanding the Black Power Movement’s history and its context in American culture.

“People now will say these protests are illegitimate because they aren’t done the same way they were in the past, or that we should learn from the example of Dr. King,” says Robinson. But his research shows the activists of the 1960s and 1970s didn’t separate their work into “right” and “wrong” or even successful or unsuccessful.

“There’s this image of what a movement looks like,” he says. When current demonstrations don’t mirror that image, he finds that modern activists become disillusioned. Robinson flatly refutes this notion: “It’s messy now and it was messy back then,” he says.

By studying the past, activists will see that even the most prominent Civil Rights leaders made errors and changed tactics. Robinson wants the people involved in the current movement to understand they should feel empowered, even if they don’t have all the answers.

Story by Elizabeth Yost, Clark Honors College Communications