CHC’s Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program offers students a window into what it’s like to get an education behind bars.

When Tamir Eisenbach-Budner, a Clark Honors College senior, walked through an Oregon prison for the first time, it was unlike what he saw in the movies–people constantly yelling and shaking the bars of their cells. Instead, he walked through an orderly place with strong security, where inmates were going about their day. He quickly realized that it’s “a place where people live first and foremost.”

It wasn’t until the fifth week that the CHC’s Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program students were able to tour the facility in its entirety. They walked past the solitary confinement unit and tight prison cells where many incarcerated individuals spend up to 20 hours a day.

One of the most intellectually stimulating spaces Eisenbach-Budner had ever come to know was also a place of profound isolation for many.

“The tour was one of the most impactful days because for the beginning of the program, your only context is this classroom full of positivity and connection,” says Eisenbach-Budner. “Once you see the rest of the prison, you understand that room is a refuge. The rest of the prison is not like that. It’s a bleak place.”

The University of Oregon is one of more than 100 institutions in the United States that have sponsored Inside-Out courses. The UO's Prison Education Program runs Inside-Out classes, which gather campus-based students together with incarcerated individuals to learn within a classroom setting. The classes, which take place within Oregon’s prison system, create a space where students of different backgrounds can come together to learn about both the subject of their course and each other.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with nearly 2 million people behind bars. For these individuals, access to education can be a key factor in improving their quality of life. According to an article by the Washington Post, participating in higher education programs helps inmates seek parole, helps with post-release employment, and decreases a person’s likelihood of being rearrested.

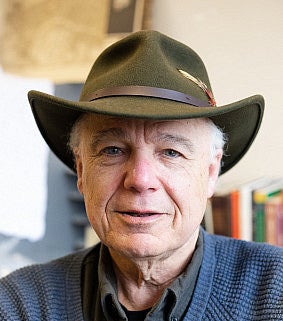

“They’re our fellow citizens,” says CHC Professor Steve Shankman, who taught the first Inside-Out class at UO. “We need to understand why there are so many people in prison in the United States, and the nature of our responsibility to those living inside the prison walls.”

Eisenbach-Budner is taking his final steps toward completing a degree in economics and planning, public Policy, and management with a minor in Legal Studies. This spring marks his second time participating in the Inside-Out Program.

“I’m taking 20 credits right now and spending an extra 150 hours this term that I wouldn’t otherwise be doing. That’s how much I wanted to take this class again,” says Eisenbach-Budner. “It’s not work; every moment of it, whether I’m reading the book, writing the essays, driving in the van or participating in class, it’s all deeply joyful.”

Throughout the past three years, Eisenbach-Budner has interned with the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, which advances criminal justice reform in Oregon through case work, research, and legislative advocacy. Although legal work is nothing new to the senior, the Inside-Out program was his first introduction to meeting inmates face-to-face.

Going inside prisons is how we come to understand the people inside–and the systemic issues with the criminal justice system, Shankman says.

This term, two groups of CHC students are doing just that. Professor Anita Chari is instructing her course, “Autobiography as Political Agency” at the Oregon State Correctional Institution. Shankman will also be teaching an Inside-Out section, “Ethics and Literature,” at Oregon State Penitentiary.

“The whole idea of the class is second chances,” says Shankman, “to accept the fact that people make mistakes, which hardly means that our lives are worthless.”

Before Shankman could launch Inside-Out at UO, he completed training at Graterford State Correctional Institution, a maximum-security prison in Philadelphia where the program began. There, he began thinking of the type of course he wanted to teach and workshopping it with fellow instructors and inmates. By spring of 2007, he was ready to teach his first Inside-Out course.

“We got a lot of pushback,” he says. Some faculty within the college believed the program would be too dangerous. But the then-director of the Honors College, Richard Kraus, was supportive of the idea. He even attended the first UO Inside-Out commencement ceremony at the Oregon State Penitentiary.

From there, the program only grew, becoming one of the Honor College’s most sought-after offerings. In his time teaching within prison walls, Shankman spoke of the “remarkable dynamic and hospitable space” the he and his students created. For “inside” students, the opportunity to learn and interact with people from the outside world is something inmates treasure.

“They all say that for those hours they’re in the classroom, they feel like they’re not in prison,” says Shankman. But inside students aren’t the only ones who benefit from the program. CHC students in Inside-Out classes get to learn alongside people who deeply value their education, says Shankman. The experience often challenges them to be fully engaged with the course, in large part so that they don’t disappoint their peers.

“Prison is a difficult place to have a learning experience, because so much of the system is designed to prevent connection,” says Chari, who has been teaching her Inside-Out course for 10 years. “And yet the paradox of teaching in the Inside-Out program is that these are the deepest, most connected experiences in education that I’ve ever had.”

When reading a book on solitary confinement in one of her classes, it became clear that several of Chari’s students had personal experience with isolation. In a typical classroom setting, it can be easy to talk of liberation and oppression in an intellectual manner, she explained. In that moment, however, students acknowledge the realness of the conversation and create a space where their peers had the support to reflect on their experiences.

Students in Inside-Out classes never share their last names, but in the classroom they share their imperfections, says Shankman. Outside students, in their other classses, are often afraid of making mistakes, he says. In the program, however, students are encouraged to be vulnerable. They spend much of their time in the classroom sitting face-to-face with peers in small group conversations through a trademark exercise known as “the Wagon Wheel.”

Shankman has seen how the class has enabled outside students to reconsider their preconceived notions of prisons and incarcerated individuals. They’re able to discuss ideas with inside students that challenge the stereotypes they may see on television.

“This class completely transforms their way of thinking about the prison population,” Shankman says.

For Eisenbach-Budner, this proved to be especially true. His time spent digesting literature, having deep conversations, and exchanging life experience with the inside students has increased his empathy for others and his sense of human connection, he says.

“Building these connections has been so affirming for my own optimism and faith in humanity. It’s emotionally nourishing to see all of my classmates come together to create this positive experience, even amidst a lot of bleakness,” says Eisenbach-Budner. “Everyone has something to add. Everyone can become better versions of themselves. It’s been transformative for me to come to understand those things on an emotional level.”

Still, the experience is also, in many ways, bittersweet, Shankman says. Over the 10-week course, students become close. On the last day of class, students must face the emotional challenge of realizing they’re about to lose that connection.

Outside students are prohibited from contacting inside students after the course ends. These boundaries are essential to ensuring courses can continue to be offered. From the start, students are told what personal information they can share and what they cannot. Outside students are absolutely discouraged from trying to conduct research on their peers on the inside.

“I try to prepare my students,” says Shankman. “You have to go in knowing that it’s going to end.”

Saying goodbye to the “room where it feels like humanity is at its absolute best” was painful for Eisenbach-Budner, who shed tears on the last day.

“During the first class they all filed in wearing identical blue sweatshirts. Many of them appeared similar. All their faces just kind of blurred into one for me,” says Eisenbach-Budner. “But within just a couple of classes, every person’s personality had been fleshed out. I learned about the science fiction writings of one and the accomplishments of another one’s daughter. We had inside jokes, and we were all becoming real friends.”

One of the hardest parts about saying goodbye is that it’s a final one. The inside and outside students become really invested in each other's lives and although the course only lasts one school term, the effect the students have on each other lasts a lifetime.

For Eisenbach-Budner, the personal mission of carrying empathy he has nurtured during his time with the Inside-Out program continues.

“The main thing that I took away from the class is that there are many incredible, insightful and kind people who are locked in prison. Many will be for the rest of their lives,” says Eisenbach-Budner. “I don’t think this is right. I think it reflects a terribly broken system. On the other hand, it was also inspiring to learn that there’s beauty that can be found in everyone and every setting.”

- Story by Elizabeth Yost and Keyry Hernandez, Clark Honors College Communications

- Photos by Ilka Sankari, Clark Honors College Communications