On November 29, 1847, Presbyterian missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and 12 others near Walla Walla died in an attack that came to be known as the Whitman Massacre. In 1850, five Cayuse men voluntarily submitted to federal troops, although evidence suggests that these five may have had no direct involvement with the killing. They were brought to the old territorial capital of Oregon City, south of Portland, where they were tried, convicted, and hanged for the murders.

How were you introduced to the subject of the Cayuse Five, and how did you realize it could be a class for CHC?

Michael Moffitt: I wanted to figure out something to do with students in the coming year that would be of benefit to students and to one or more of the tribes here in Oregon. I had no clear idea what that might look like. I consulted multiple times with Howie Arnett, one of the leading experts on Indian law in the state of Oregon. He has taught at Oregon Law for many years, and he was one of the people who served on my Advisory Council when I was dean at the law school. I met with Howie often, and in that context, we talked about possible outreaches. We considered students serving as clerks for tribal courts. We considered an alternative spring break style service trip to a reservation. We kicked around lots of ideas over a couple of months. Howie has worked with Bonnie Connor, the director of The Tamastslikt Cultural Institute of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. He shared with her some of the ideas he and I had been kicking around. It was Bonnie, I think, who first raised the possibility of doing work on the case of the Cayuse Five.

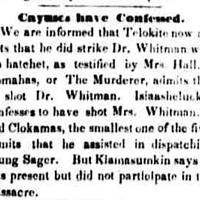

A newspaper clipping from 1850 documents the submission of the Cayuse members to the Federal Army.

How did you decide to bring it to life?

MM: My background is in conflict and dispute resolution. I thought it would be really interesting to see some ways in which my professional passion might intersect with this opportunity. My understanding is that at some point a while back, someone had proposed a form of reconciliation process with the tribal community regarding the Cayuse Five. Such processes can, in some contexts, be powerful and important. And in some contexts, they’re not appropriate. My understanding is that in this particular context, when approached about the idea, the Umatilla said, essentially, “Reconciliation? Well, maybe someday. First, give us our guys back.” The problem, of course, is that the burial location of the Cayuse Five is unknown. Bonnie, Howie, and I agreed that a bunch of work in reconciliation in the abstract would not be helpful. But what if we could work on this precondition to move toward possible reconciliation work? What if we tried to find the burial site?

I’ve had incredible support along the way. I have the great fortune of being a Phillip H. Knight Chair in Law, which comes with some funds to support research and teaching activities. Phil and Penny Knight were generous in not placing many restrictions on its use, and I just had the notion that there might be something useful to do with some of that money. And Dean Stabile encouraged me to think about this in terms of a colloquium rather than just a side project. In the span of just a few months (lightning speed, from a typical academic perspective), this has gone from a vague notion to a spring colloquium offering.

What will the class look like, day to day?

MM: We plan to launch the class at the Whitman Mission, at the site of the 1847 murders. In coordination with Kate Kunkel-Patterson of the Whitman Mission National Historic Site, colloquium students and a number of tribal members will participate in several hours of educational and other programming. Some of it will be traditional “first-day-of-class” sorts of things. But the other part of it—and this is super important to me, and I feel grateful that this can happen—is that one or more elders from the tribe will come and bless the work that we are doing. It’s critical that we work to understand the context in which we are doing this work, and we will take every opportunity to integrate our work with that of others. This is not just a theoretical, academic question. This holds current meaning for many, and we need to understand that if we are to aim our efforts wisely.

The next day we will pile into a bus and drive to Oregon City. We have a really good idea of where the hanging took place, and we have some idea of where the trial and jail were. If the graves are to be found, they will be found within an hour’s walk from the site of the public execution. So the second day of the course will be spent on the ground where we will ultimately be making our guesses about where the burial site is.

For the rest of the term, we’ll meet on most Friday mornings. My current vision is that we will be co-creating the content for the course, following leads and interesting questions. I hope to bring in outside experts to assist us so that on each of the remaining days, we will look at one category of existing documentation or evidence. For example, I am sure that we will spend a day looking at the available trial records so that we can understand what happened between the time when the men voluntarily submitted themselves to the federal troops and when they were hanged. We’ll look at old land records to try to figure out who owned which plots when. I’m hoping to consult geologists and geographers because one of the accounts of the execution includes mention of the bodies being taken by a handcart and buried near Abernathy Creek. We know where Abernathy Creek is today. We’ll need help knowing if we can know where it was in 1850.

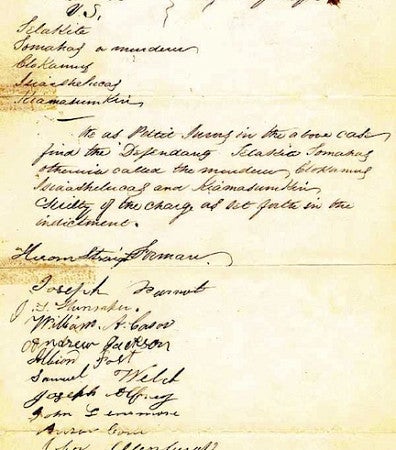

The handwritten verdict in the trial of the Cayuse 5.

What other tools will you use in class to try to find the burial site?

MM: Well, this may not be a case of searching for physical remains, ultimately. The burial site may have been exposed to too much water over 170 years. It may have been the site of excavation or construction one or more times. But it’s possible that the site is intact. We just don't know, and won’t know, until we engage in this research. We will aim to be productive and helpful in our explorations, leaving a clear trail of our research down every line of inquiry that we can imagine.

How will this be different from other courses you’ve taught?

MM: I’ve never done anything like this. The students and I are honestly going to just try to run down the rabbit holes, most of which are not likely to lead to the answer. But if we can put in the legwork, you never know. At a minimum, I think we can help move the needle on this historical question. I’m excited to learn and work alongside CHC students on this project.