The Clark Honors College Mission

The Robert D. Clark Honors College cultivates an inclusive, dynamic community of learners who are committed to equity, the pursuit and sharing of knowledge, and making a positive impact on the world. Through a challenging, interdisciplinary curriculum, personalized advising and mentorship, the CHC supports each student's path to timely graduation and success. By encouraging personal and career growth, the CHC equips students with the skills to lead purposeful lives and contribute meaningfully to the world.

Shared core values of the Clark Honors College

These principles guide our commitment to supporting students through their educational journeys and beyond.

Inquiry: cultivation of curiosity, knowledge-seeking, and the pursuit of solutions that incorporate different perspectives and areas of knowledge

Care: intentional practices that support the holistic wellbeing of all members of our community

Equity: policies and procedures that ensure that every member of the CHC community is treated fairly and has the access and support they need to thrive

Impact: work that improves the world

Creativity: freedom to imagine and create; the generation of innovative ideas

Ethics: adherence to principles emphasizing integrity, fairness, and respect for others; prioritizing the collective good over individual interests, or the “we” over the “me”

About the Robert D. Clark Honors College

At the Clark Honors College, we offer students the opportunity to have a small, liberal arts college experience along with the benefits of a major research university and its cutting-edge facilities. Our small, discussion-based class sizes average 15 students, allowing them to develop one-on-one relationships with award-winning faculty members.

We emphasize critical thinking, problem solving, and collaboration. Honors College scholars are taught in a way that improves both communication and writing skills. The exclusive curriculum in natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities replaces all core education requirements at UO. Students follow a pathway toward involvement in hands-on research, along with access to internships and other professional opportunities.

The Honors College has experienced record growth over the last several years. Currently, there are more than 1,360 students at the Honors College. The incoming Class of 2027 is diverse in so many ways:

Robert D. Clark and the history of UO's Honors College

The University of Oregon opened the Honors College in September 1960 with a freshman class of 129 students. It became the first public honors college west of the Mississippi River. The Honors College’s first home was in the basement of Friendly Hall, a structure originally built in 1893 as a men’s dormitory.

In 1975, administrators named the college the Robert D. Clark Honors College in recognition of the man who was retiring as UO president. Robert D. Clark served as president at the University of Oregon from 1969-75.

He had been turned down for enlistment in the military because he was nearsighted, so he moved to Eugene to teach public speaking to men in the university’s ROTC program. After the war ended, he was delighted to be offered a permanent position in the Speech Department. Gradually, he left significant marks of his influence, establishing forensic programs, traveling the state with his students for presentations and contests, as well as writing essays for speech and rhetoric publications and making appearances at conferences.

Clark was active in the university, and in the community, too. He attended the First Congregational Church and soon had the minister and his wife coming over for Sunday dinners, while his own wife, Opal, established a Sunday school program and later a preschool in the church spaces left unused during the week.

Soon, he was promoted to head of the department, then to assistant dean and dean of the College of Liberal Arts.

How the Clark Honors College came to be

Clark had read about programs on other campuses, large and small, designed for superior students. He wondered how something of the sort could be established at UO.

He found a determined group of faculty friends who wanted to try an experiment with designing classes for an honors program. As dean, he met with them and was very enthusiastic. However, it would require a major reform of the distribution of teaching assignments and salaries, along with some care to avoid creating a jealous reaction if they were taking money from departmental budgets already quite pinched.

In order to start the program and demonstrate its worth, some of the professors were willing to teach the first offerings of such classes as experiments, working as volunteers. Their aim was to help establish a new form of course instruction with small classes, a demanding curriculum, and much discussion, in a special community of students. The students joined at first by signing up for Honors classes in what was to be started as a community. Faculty taught in rooms in the back of a popular restaurant, beginning the honors program in a setting of the unconventional.

Clark at San Jose State University

After that, in the middle of his career, Clark moved to California to accept the offer of president at San Jose State University. There, he encountered Ronald Reagan, who was governor at the time, and Richard Nixon personally as they verbally attacked protesting San Jose State students and professors. Clark showed his support for faculty and students and their right to protest.

Clark was also called in to address the problem of the famous San Jose State athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who had won Olympic medals in Mexico City in 1968, lifting their fists on the podium in support of the fight against racism in the United States.

This unleashed a tremendous upheaval that stirred international condemnation. It did, indeed, follow the careers of those two athletes all their lives. But Clark had called them fine young men, and he heard from them at Christmas for the rest of his own life.

Clark as University of Oregon president

When he was offered the chance to return to his beloved University of Oregon to become the next president, he found protestors in Eugene, as well. He continued his defense of protests when they arrived at the front door of McMorran House, where he invited them to come in. Even when students occupied his office at the university, he allowed them to stay for one day, and he spent some time listening to their views. However, the governor interrupted Clark by sending National Guard troops, who entered 13th Avenue behind a barrage of tear gas.

The students escaped from the Office of the President, and the troops were drawn away from the confrontation after they were widely photographed by the news and a visiting film crew. That’s when the tear gas stopped. Clark and the governor later became good friends. Concern about the environment and the vulnerable forests of Oregon were their mutual obsessions.

Clark held to the principal of allowing exchange but not violence. In the next week, both the UO and Kent State University in Ohio faced activist students trying to burn down the ROTC. At Kent State, four students were killed and nine wounded by the troops. A few days earlier at UO, police were given the order to fire at the students. The police were not from campus and campus officers didn’t follow the order. The students were disbursed without any violence.

The Honors College flourished and impacted higher education in the state of Oregon and, indeed, increased interest in special honors programs at a number of other American universities.

Chapman Hall Renovation

The interior of Chapman Hall was totally remodeled and reopened in the spring of 2018. The classrooms were redesigned to house the CHC’s signature seminar-style classes. Integrated classroom technology, community spaces for students and faculty to meet and mingle, and dedicated student spaces for social and academic activities have made Chapman more inviting.

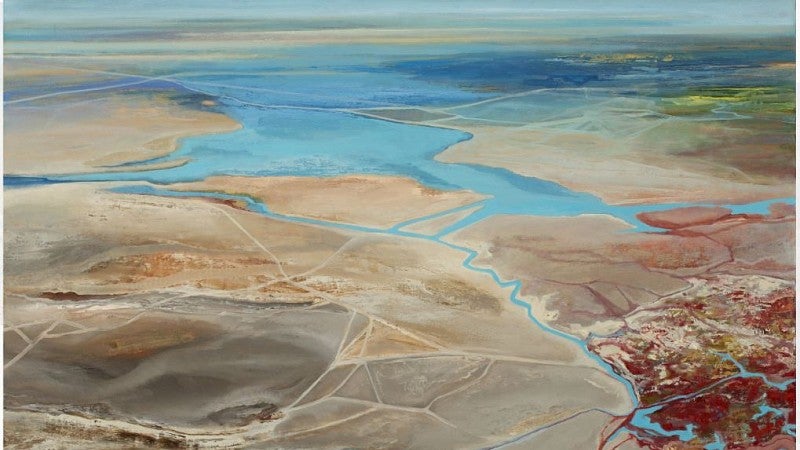

The Chapman renovation also allowed for Clark Honors College to be a designated home to a variety of original artwork created by Oregon artists as part of the state’s Percent for Art program. Learn more about these 17 works and the artists behind them on the Percent for Art at Chapman page.