A Student Journalist, International Politics, and a Human Connection

By Derek Maiolo

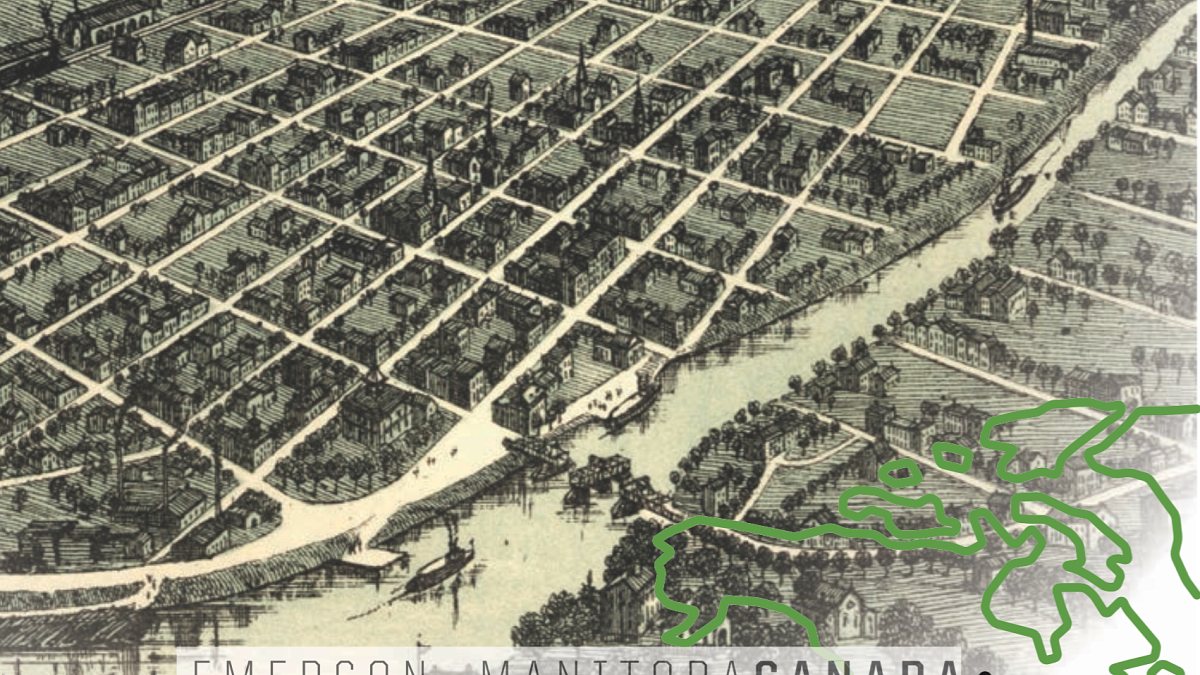

I spent my finals week of winter term in Manitoba, Canada, reporting for the UNESCO Crossings Institute — a radio news show based out of the University of Oregon. In the small border town of Emerson, above the North Dakota state line, droves of asylum seekers had been crossing illegally since Trump was elected in the fall.

A loophole in laws between the two countries allow asylum-seekers who were deported in the US to file for a second claim in Canada — but only if they cross the border illegally. With Trump’s Muslim-targeted travel bans and general hostility toward migrants, families from countries like Libya and Somalia feared harsher deportations in the US and risked the trip north for a second chance at asylum.

These are notes I wrote during and after the trip. I am grateful to the Crossings Institute for allowing me to do the kind of reporting that before I could only dream of.

Monday, March 20th

8 p.m.

I got to Emerson a few hours ago after driving from the airport in Winnipeg. The border town’s Main Street has four businesses still in operation: a small grocery store, an auto shop, an ice rink, and an art studio with a thick row of plants in the window.

There are only two places to stay in Emerson: The Maple Motel and The Emerson Inn. The latter is made entirely of wood that’s rotting in some places and falling off in others, but a sign says it recently changed management, plus they had a new café. I overlooked the exterior and chose to stay there.

Wayne Pfiel, the new manager, rented me a small room with a microwave, ash tray, and a TV missing a few nobs, the power button being one of them.

The bathroom has similar quirks. Where once was a shower head is now just a bare metal pipe sticking out of the wall. When I turned the hot water on, a thick stream of clay-colored water gushed out of it. I decided not to take a shower.

Still, I can’t help but feel like I’m in the most wonderful place in the world. I’m on the start of a great adventure, perhaps the most important assignment of my journalism career. Now all that’s left is to wait until the morning when I can interview some of the people here.

10 p.m.

I’m too excited to wait. I’ve been reading up on where most asylum-seekers have been crossing into Emerson. There’s a place not far from my hotel by the railroad tracks where families were found last week. It might be a bust, but I want to plan a bit of a stake-out to see if I can talk with some of them just as they’re arriving. It would be incredible footage for the radio story, and quite the tale to tell back home.

10:30 p.m.

Everything is ready. I have potato chips and trail mix, water, my audio recorder and a camera. Plus some books to pass the time.

I used Google maps to scope a spot that’s near the tracks but far enough from town that I would see any migrants before the police found them. Let’s see what happens.

11:15 p.m.

It’s strange to be here. I feel like I’m breaking the law, but there’s no indication that this is a

restricted area. The only thing designating the border line is the dirt road in front of me and a

metal pole to my left with the Canadian and American flags on their respective sides.

It’s already 10 degrees, so I’ve kept my car running for the heat.

1 a.m.

A policeman just drove by and stopped to ask what I was doing. I told him I’m a reporter and about the story I’m covering. He just rolled his eyes and kept driving — he’s probably seen a lot of my kind lately.

Police arrest refugees found crossing the border unofficially, but most who cross want police to find them so they can claim asylum in Winnipeg. They’re released from custody after they make their claim.

Later, I saw the same cop car park a couple hundred feet in front of me, facing a barren field in U.S. territory, lights off.

2 a.m.

It’s nearing subzero temperatures outside now. I’ve been waiting for hours, but nothing so far. The cop left a few minutes ago, so I took his spot on the small hill. I’ve been looking out in the darkness trying to see a light or bodies shuffling in the snow. Nothing.

2:30 a.m.

I took one last drive down the border-lined dirt road until it disappeared into a frozen field. Something tells me to stay, but it’s been a long day and I need to get some sleep.

Tuesday, March 21st

10:30 a.m.

I just got back to my room after breakfast at the café downstairs.

The first thing the waitress asked me, “Did you hear about the folks who showed up in the middle of the night?”

According to her, a group of asylum-seekers had gone to the Maple Leaf Motel at 3 a.m., not even half an hour after I’d made it back to the Inn, less than 100 feet away.

I can’t believe it! Stupid me. Stupid. I feel like I let a huge opportunity slip right through my fingers. If only I’d stayed just 30 minutes more — I would have had the interview of a lifetime!

But I can’t think about that now — I have a day of interviews with people around town.

3 p.m.

I drove to the local fire station, where Chief Doug Johnson greeted me at the door. He doubles as the paramedic and has helped families who get stranded in blizzards as they make their way over the border. I asked him about the migrant situation.

“The town is usually so quiet,” he said. “But at night it comes alive.”

We drove to the local golf course and took a service road. Johnson stopped the truck in front of an old barn with a crowd of footprints etched in the snow.

“We found a group of families here a week ago,” he said. “They were huddled here in the cold for hours before we got to them.”

We drove back to town in silence. At the station, I asked whom I should talk with next and he mentioned Sharon Cory — she runs the art studio downtown. He described her as “very opinionated.”

5 p.m.

Sharon Cory may be my favorite person in this entire town, even if she is “very opinionated.” Her studio was a literal breath of fresh air thanks to all of the tropical plants in her window.

Cory is Lebanese — her grandparents came to Canada as refugees, so she cares deeply about those needing a new home. She has helped Syrian families displaced by their civil war at aid centers in Winnipeg. She strongly supports the refugees and wants softer borders with the U.S.

After speaking firsthand with people displaced by the crisis and seeing horrific images on the news, she started an abstract art series on the migrant crisis unfolding in her own backyard.

“I’m processing the influx of dark skin because I know that’s affecting a lot of people here,” she said, mentioning racist comments she’s heard from her neighbors.

She said something else that struck me about the importance of her art.

“The only way I can deal with these emotions is to paint them out,” she said.

I know what she means — writing has always been my way of coping or expressing something intangible, a feeling or memory that nags at me until I get it on paper.

Others in the town, like mechanic Wally Turton, do not share Cory’s opinion on the migrant situation.

“I don’t want to be an ogre but enough is enough,” he said, worried that the refugees will take Canadian jobs and overburden the welfare system.

Wednesday, March 22nd

11 a.m.

Winnipeg is great — the roads with their potholes are not. I have to say I expected better public works in a country with socialized medicine, but at least I’m driving a rental.

I’m headed to the Muslim Women’s Institute — it’s the only nonprofit group in the city that specifically serves that population. I’d arranged before my trip to visit the Institute and help with their weekly food drive, as well as speak with some of the asylum-seekers.

12 p.m.

The Women’s Institute is in a single-floor office space in the international district of the city.

With the flood of asylum-seekers who have crossed in recent months, the small organization has had trouble keeping up with people’s needs for basic necessities like food and clothing.

There is a constant flow of people here. The executive director, Lauren Martin, said someone would give me a tour of the place, but the waiting room is full of people registering for the free food pantry and access to donated necessities — diapers, plates, winter boots.

1 p.m.

Ahlam Jasim just gave me a tour through the Institute. She is its only paid staff member.

“We’ve been existing on a shoestring,” she said.

The rest of the more than 10 volunteers— asylum-seekers themselves— get nothing but a résumé boost for future employment in Canada, given that their applications for asylum are approved.

Jasim, born and raised in Iraq, fled her home after her husband was executed by the Saddam regime. When she arrived in Winnipeg, the women here became her support group. She’s been with the Institute since its founding in 2006. Now, she said she wants to be the one to help others.

She does seem like a mother to the families and volunteers of the CMWI. Everyone here knows her by name, and she stops to greet each person by theirs.

6 p.m.

The last families just left the food drive. This has been one of the most fulfilling days of my life. Just like the waiting room, there was a constant line of people from all over the world.

Most spoke Arabic but English came through sometimes, French others — other native languages, too. It was such a beautiful blend of cultures helping each other. A Syrian father gave potatoes to a Somalian family, two young Libyan girls helped an old woman from Ethiopia.

I talked with some of the families, often with the help of an interpreter. Their reasons for fleeing their home countries — war, persecution, threats of torture — were painful to hear. Still, they greet one another warmly. They smile and make jokes.

Despite all the visitors, there are leftovers, and these the volunteers take home to their own families.

9 p.m.

I’m back at the hotel, thinking about the last couple of days. The fears people have about these families are so misunderstood. They’re not here to steal jobs or get a free ride — they just want a safe life for their kids.

I want to show people, like Wally in Emerson or friends from my conservative hometown, the humanity of the ‘foreigners’ they fear so much. I want Trump to stop equating ‘Muslim’ with ‘terrorist.’ I wish they could meet Ahlam Jasim.

But look at me, going on like I know the answers. I haven’t even been here a week, and those women at the Muslim institute have been dedicating years to helping others. They’re the heroes, I’m just here to write about them.

I think of Sharon Cory and her paintings — her only way to respond to the suffering she sees. I hope, like her, that my work here makes someone, anyone, see that these people are just that — humans, in need of our help. I want my trip here to mean something to others.

My plane leaves tomorrow, so I need to get some rest. This has been Derek Maiolo, reporting from the experience of a lifetime.