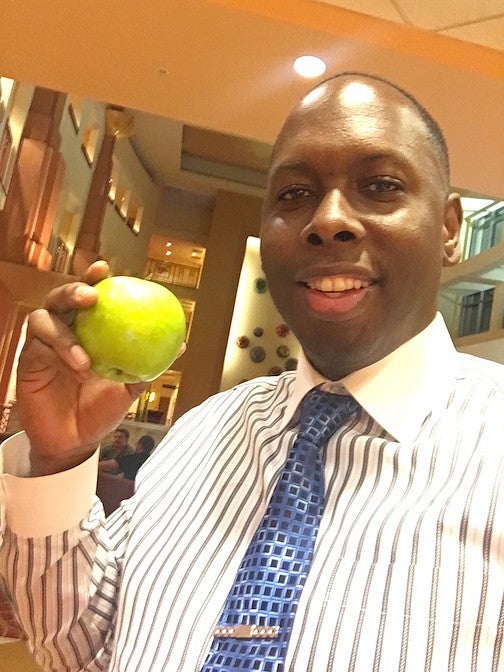

CHC junior Tamir Eisenbach-Budner helps gain clemency and a new start for Portlander Jamar Summerfield

Story by Lauren Tokos, CHC Communications

Photos by Jasper Zhou, CHC Communications and courtesy of Jamar Summerfield

May, 2022

It was the kind of summer day in Portland that is bright and balmy; playgrounds were packed with children running and teenagers lined pool sides. In many ways it was typical, no different from the day before it or the day that would come after. But for Jamar Summerfield, it was a day that reached beyond the sun or the nice breeze, and one that had taken 20 years to arrive. It was the first day that he would be able to walk into his six-year-old daughter’s school to pick her up without the label as a dangerous felon.

Growing up in the ‘80s, Summerfield was one of several children in his single-parent household in a predominantly Black neighborhood in Northeast Portland — he went to school, played sports, and hung out with his friends on the weekends and after school.

“One of my childhood things I wanted to do was work for the FBI,” Summerfield says. “You know, I used to want to be a criminal profiler for the FBI.”

But his path as an adult would never bring him close to becoming an FBI agent; his neighborhood was stocked with gang violence and drug activity with little opportunity to avoid it. His siblings and friends were already immersed in running drugs and involved in gangs.

By the age of 11, Summerfield was sitting on doghouses, scouting for signs of police to alert the drug dealers below on the street. The older he got, the more involved he became with the life knew he didn’t want. The money he made scouting, running, and dealing drugs went to support his family, the only one who was contributing to the household, though his siblings were making money doing the same thing. He was in deeper than he had ever imagined, and he didn’t see any way to end it.

So he made a choice.

Summerfield decided to leave the life he knew, gathered an assortment of odd jobs to make a living, and enrolled in a business class at a community college to learn how to sell McDonald’s franchises.

Not long after, an incident in Summerfield’s neighborhood — the same one he’d grown up in — resulted in a felony charge, putting him back on the track that he’d been able to avoid. Summerfield openly relates that the offense was less than honorable but maintains that he acted in self-defense. Never wavering from that position, he received a prison sentence stretching 90 months — termed a Measure 11 sentence that holds no possibility of early release or a reduced sentence — in the Oregon State Penitentiary.

Summerfield’s freedom, his rights, his potential hopes for a family, a steady job and a good life were now beyond his reach. When he left prison almost eight years older and as a felon, the possibilities for those things no longer existed.

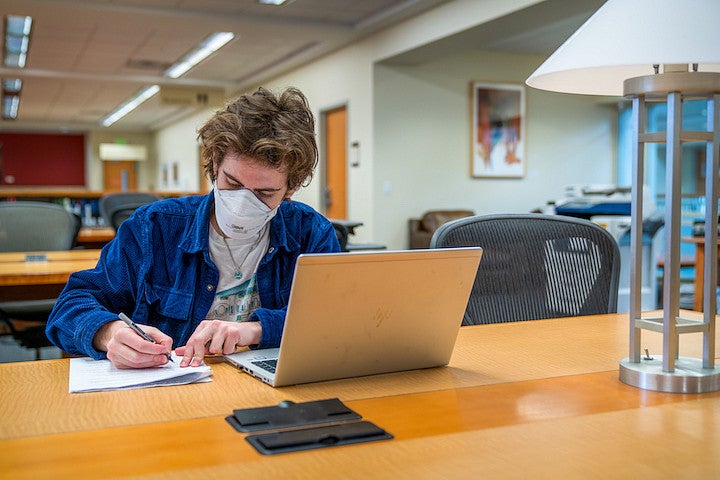

During the first summer of the pandemic, Tamir Eisenbach-Budner a Clark Honors College junior, spent those months in an internship at Lewis & Clark Law School Criminal Justice Reform Clinic in Portland fighting for the clemency of a man he had never met before.

Before the internship, Eisenbach-Budner had been interested in law, he says, specifically criminal justice reform.

“I think of the criminal legal system as the sharp end of a lot of America’s social and economic policy,” he explains. “Making it more humane, rehabilitative, and equitable has the potential to improve the lives of not only the millions of people involved in it, but also the communities they’ll re-enter.”

He had also heard that Professor Aliza Kaplan, director of the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis & Clark University, provided case work for low-income communities and indigent people in Oregon, and offered the opportunity to do high-level work that wasn’t typically characteristic of most entry level internships.

Eisenbach-Budner applied for the internship at the clinic and secured it in the spring of 2020, initially working on reviewing letters from incarcerated individuals who were seeking clemency petitions. After several months, Kaplan, Tamir’s advisor, noted that his work was exceptional and assigned him a case.

Jamar Summerfield applied to the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic for representation on a clemency case. He wanted his rights back, he wanted a chance for a good life for himself, and his family. Since his release from prison, Summerfield had become the community member that, as a child, he had imagined he would be.

“I don’t really like to talk about our clients or details of their cases,” Kaplan said. “But generally, Jamar had a serious crime from the 1990s that he served time in prison for. And he finished everything he needed to do post-prison; everything that was asked of him by the state was completed. And he was in the world doing amazing things and holding down numerous jobs and working in his community. Yet this very old conviction was making it really hard for him to be in the housing he wanted to be in, to get promoted at his job or to apply for certain jobs. It was really limiting him.”

Many people would consider Summerfield an exceptional success story who turned his life around post-incarceration. After his release from OSP, Summerfield secured a job as a sales manager for a communications company and started an initiative called S.O.S Lifeworks, which helped navigate clients from the inner city to locate opportunities they wouldn’t have had access to otherwise. Several years later, Summerfield got a position at the Oregon Liquor Control Commission as a distribution worker and also served as the diversity committee spokesperson at the OLC.

“A lot of people are institutionalized; if they are, they attach themselves to what happened in the past. But for me, mentally, I wasn’t going to attach myself to those things. I was going to attach myself to what I was doing in the present and the future, so then in the future I could be a tax paying citizen and agent for change,” Summerfield says.

He was determined that his past would not be his only story but that his future would be a positive force. He was disheartened by the limited opportunities for rehabilitation in prison. His only options in OSP were courses in cognitive behavioral or anger management. A select few of his peers were given hands-on training in areas like plumbing and carpentry, but typically, “You come out almost the same as you went in,” he says.

“You are scrutinized, coming through the door, pertaining to getting a job,” Summerfield adds. “When you are trying to get a job, you have to explain. Not only that you had a felony, you have to explain the details of the felony to people who are not even comfortable with being around people who have (a felony).”

Several years earlier in 2015, he landed a full-time job at the Oregon Health Authority as a registration specialist. In 2018, Summerfield co-founded the grass-roots organization Solid Ground PDX, assisting single parents to gain financial assistance, and reduce the recidivism rate for black Portlanders with a criminal record. He helped former gang members reintegrate into society and provided resources and assistance to remove women and children from domestic abuse situations, creating a one-stop manual single parents to find resources in Multnomah Country. Solid Ground PDX grew, increasing its mission with a focus on bridging the equity gap and providing financial literacy education.

“It's not quite a legal process. It's not like in the courts,” he says. “It's more personal, you know, people are encouraged to share their story, kind of like an autobiography. It's really about the governor seeing you human to human and saying ‘I'm going to respect who you are now.’” —Tamir Eisenbach-Budner

It was at a Solid Ground PDX brainstorming session about potential projects that the idea of filing for clemency came to Summerfield.

“We came up with different things that we wanted to tackle. And I said I think that we should tackle expunging people records,” Summerfield explains.

He reached out to a public defender he knew through his community work and began an outreach search for people who wanted to expunge their records by working with the Portland Metropolitan Public Defender's office.

Fifty people responded, but Solid Ground PDX was lacking the funding necessary to start a full process for all 50 and only had the participation of one public defender. The progress was slow, but successful, expunging the records of around 30 people. One of the participants who had his record expunged went to work in the public defender's office, and then connected Summerfield with Kaplan at Lewis & Clark Law School.

According to Kaplan, every governor has the power to give present or formerly incarcerated individuals clemency. Governors can grant commutations, which alter presently incarcerated individuals’ ongoing sentences and governors can also grant pardons, which removes felony convictions from a formerly incarcerated individual’s record. Summerfield filed for the latter.

Kaplan assigned the case to the young intern who had impressed her with his work ethic and commitment to helping others who had experienced social injustice.

For the following five months, Eisenbach-Budner worked alongside Summerfield under Kaplan’s supervision to draft an extensive clemency petition for Oregon Governor Kate Brown.

Due to the limitations of the pandemic, the two met weekly via Zoom for lengthy conversations. Summerfield disclosed intimate details about his life, and Tamir took notes, documenting every aspect of Summerfield’s past and present. Together they drafted a clemency report that had the potential to not only clear Summerfield’s conviction, but also restore his opportunities to provide for his family while still helping others.

As Eisenbach-Budner puts it, he was the documentarian of Summerfield’s life. During his previous work as an intern, he read through hundreds of clemency applications, and noticed similarities and patterns as he moved from one to the next.

“So many people were incredible; but (they) didn't know what to write, they would only write one or two pages, they would just answer the questions as they were asked.

If you actually want a chance at getting clemency, you have to go through this arduous process that involves an explanation of your childhood, the factors that led you into criminal behavior, your crime, your incarceration, your rehabilitation, your activities since then, and your hopes and plans for the future,” he adds.

The personal history is only a part of the application, Eisenbach-Budner says. Then there are letters of recommendation, photographs, and notarization, making the process confusing for those who have no help navigating the channels.

“It's not quite a legal process. It's not like in the courts,” he says. “It's more personal, you know, people are encouraged to share their story, kind of like an autobiography. It's really about the governor seeing you human to human and saying, ‘I'm going to respect who you are now.’”

As they continued to meet, Eisenbach-Budner became an expert about the ins and outs of Summerfield’s incarceration and his life afterwards. Unlike many of his peers in prison, Summerfield focused primarily on the present and future, and he devoted himself to reforming the very community that was the conduit that landed him in prison.

“I'm going to be able to go into our school. I can go to parent teacher meetings. I'll be able to go to go to the soccer games, not thinking that somebody's looking at me in a different way, you know, because they don't want you around the kids if you have a felony.” —Jamar Summerfield

Summerfield himself had to expunge his record before the clemency process could even begin. Each charge cost roughly two hundred dollars. With a tight budget and a family to provide for, it was difficult for him to pay these fines, which totaled around $1200. “I had to cut off cable for an amount of time, cancelled car insurance and took public transportation. I had to do things differently to (raise) the money because I just can’t make enough up here,” Summerfield says.

It was something he was more than determined to do.

“For me to reach out for a higher paycheck and get economic justice, I was going to have to get (the felony charge) off of me and get a seat at the table where I can speak my peace without having to explain a felony that happened over twenty years ago,” he added.

Once he started working with the clinic, Summerfield felt a hope he hadn’t dared himself to feel before.

“I had to relive what happened over twenty years ago; the process was troubling,” Summerfield says. “I was ward of the state. And I did my time. But when I came back, I told myself that I was going to show them that they had a person who could help the community and who wasn't going to be stuck on what happened in the past, but what's going to make the present and the future better for not just him, but for others. I was open to giving Tamir details that I would not divulge to anyone, because I let the past be the past.”

Eisenbach-Budner collected these details, and after roughly 25 hours of meetings throughout the late summer of 2020, he spent another seventy-five hours getting a report ready to deliver to the governor. Not only had Summerfield found an advocate in his attempt for clemency, but he also found a supporter and a friend.

“(Jamar) basically just committed himself to completely changing his life outside of prison,” Eisenbach-Budner says. “When he left there, he knew he was never going back.

He works for the Oregon Health Authority on the COVID engagement team, helping direct millions of dollars of funding towards assisting community-based organizations — and acting as a bridge between it and the communities it’s actually aiming to help. He's a great father and partner. He has been super involved in his community, mentoring gang members and other people leaving prison about how to integrate into society; helping domestic abuse victims escape their situations; driving kids back and forth to prison for visitation with their family members; he's just a superhero, in my opinion.”

Summerfield and Eisenbach-Budner worked with Professor Kaplan to finish the petition and it was filed by the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic in January of 2021. It would take six months for the application to reach the governor and for a decision to be issued.

“It’s pretty rare for clemency pardons to be granted,” Eisenbach-Budner added.

But the experience was more than an application to both men. While they waited, Summerfield began holding expungement clinics for others, to help them the way Eisenbach-Budner advocated for him. And to Eisenbach-Budner, the connection to Summerfield was more than just an experience.

“My main career hope is to serve people directly, and this was an amazing taste of that,” he says. “It showed me it is really possible to make a difference and how meaningful it feels to do so. It definitely inspired me to keep pursuing public interest law, which seems like a really good way to do that.”

Six months later, Jamar Summerfield was notified that he had been granted clemency and his record was expunged. It took 90 months and 100 hours, but he had the life he wanted back. Eisenbach-Budner, however, is reluctant to claim the victory himself. That, he adds, is all Summerfield’s.

“I want to make sure the focus is on him, that he's who we are celebrating here,” he says. “The fact that the clemency was granted, that’s all Jamar. That’s not about my work, or my quality of writing, that’s about Jamar’s lifetime of hard work and his life story. I’m just super grateful I got to be a part of it. It was definitely one of the most meaningful experiences of my life.“

And the first thought that came to Summerfield’s mind when he heard that he had been granted clemency was of his six-year-old daughter.

“That was the first thing that came to my brain,” he says. “I'm going to be able to go into our school. I can go to parent teacher meetings. I'll be able to go to the soccer games, not thinking that somebody's looking at me in a different way, you know, because they don't want you around the kids if you have a felony.

“The story is not over,” Summerfield continues, still frustrated by the lack of opportunity for people in his community. “Where are the business owners and venture capitalists who can help us reach economic justice? Where are the people who can guide us so we can build ‘pass-down wealth’ so we can help those who can’t help themselves?”

Eisenbach-Budner will return to the Clinic this summer to work on more clemency cases; Summerfield is also determined to fulfill a lifelong goal of his, and now that his record is clear, is applying for jobs in high security .

Although the two have never met in person, their ties through this experience are still quite strong.

“I thought about Tamir, knowing him for the rest of his life,” Summerfield says. “We have a young Jewish man and an inner-city Black man working together. He helped restore the freedom in my life. Even though he is from another culture, another area economically, we came together, we connected. There's a lifetime friend, a lifelong friend.”

.