Professor Judith Raiskin leads her class in the methods of using the library archives.

Photos and story by Dana Sparks, CHC Communications

June, 2019

Tucked inside the west side of the Knight Library on the second floor is the Special Collections and University Archives, or SCUA. There, an intimate Clark Honors College course, Touching Archives, gathers to dive into the collections and archive that reportedly holds more than a million items.

The small class divided themselves into two groups to specifically study items from American science fiction writer Alice Bradley Sheldon — better known as James Tiptree Jr. — and the country’s largest collection of artifacts from the Rajneeshpuram.

“My research specifically is looking at science fiction as escapism and what that meant to to her in using a male persona to write under,” said Clark Honors College student Andrew Tesoriero. Tesoriero is an advertising major and creative writing minor in the class studying Tiptree in relation to other science fiction writers and feminism.

“More so than any other kind of paper that I’ve written, any class I’ve taken, I feel like I am getting to know this person who has been dead for many, many years,” said Tesoriero. Much of his research was spent reading journals and personal letters, seemingly transporting him decades into the past to the private affairs of some of the world’s most prominent science fiction writers.

The research gathered in Touching Archives dives deeper than the more routine collection of secondary sources. Instead, the individuals in the class are taught how to directly create their own primary sources using materials collected by the university with the help of Linda Long and Professor Judith Raiskin.

Curator of Manuscripts Linda Long is responsible for gathering the manuscript collections and other materials from donors that add to the UO’s current repository. She also sees the intake and cataloging process.

The spectrum of what might pass through SCUA, outside of the Tiptree and Rajneeshpuram collections, is wide. For example, SCUA is home to a range of collections from topics like children’s literature manuscripts to Oregon communes. All of these topics and materials are managed and their relevance to UO SCUA guidelines are navigated by Long.

“There was a steep learning curve at the beginning to teach the students how to do research with primary sources,” said Long. “They are scholars, but they’re novice scholars. This gives students an opportunity to form their own opinions based on the original primary sources. It’s empowering.”

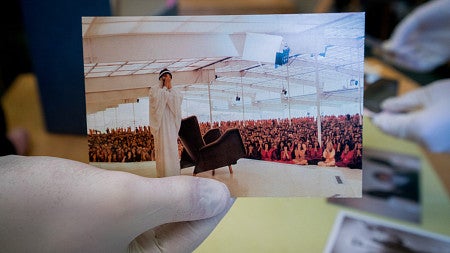

Long says that the largest collection at SCUA is actually from the Rajneesh Legal Services Corporation.

“If you whipped out a measuring tape and stacked the boxes next to each other, it would be 142 linear feet. It’s 99 containers,” said Long. “It’s a treasure trove of all different kinds of information.”

Beth Peters, a general science major and biology minor, talked about how she connected to the class after growing up in The Dalles, Oregon where the Rajneesh poisoned 751 people with salmonella in 1984. She saw Touching Artifacts as an opportunity to engage with her hometown’s history and look at how her neighbors’ lives were affected — especially in light of the release of Wild, Wild Country, a Netflix documentary about the Rajneeshpuram.

“This is a really interesting collision: a historical study as well as a social study through a general science major,” said Peters.

She conducted interviews with a person who was poisoned, someone working for the lab at the hospital and the director of the county planning office — someone who turned out to actually be her next door neighbor — while also using SCUA manuscripts.

“One thing that I realized working in the collections is the different perspectives that people will have on the same thing,” said Peters. “One event can mean something different to different people even though they’re all still involved.”

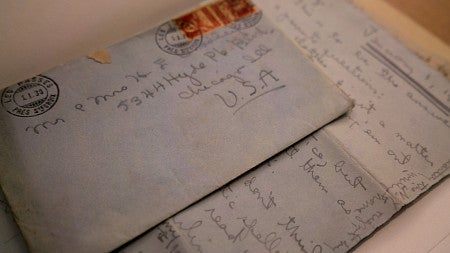

Letters from from American science fiction writer Alice Bradley Sheldon and photos from Rajneeshpuram.

The same should be said for the Tiptree collection — just one puzzle piece of a developed manuscript collection on feminist science fiction.

With Long as the liaison with special collections, Associate Professor Judith Raiskin of Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies leads the class. It was Raiskin that initially proposed the class to the university.

In the class, Raiskin says that she saw students working on high level collaboration and discussions not only with one another, but also other scholars that worked with the material. At one point during the course, the students were able to video-chat writer Julie Phillips and discuss why she used certain materials in the collection in the creation of a biography about Alice Sheldon.

“To see different perspectives on the same situation and to understand that the history you read is a perspective based on the materials before you that are not always so clear. That is really something important to take forward,” said Raiskin, explaining a sense of historical literacy that she saw students gain.

Students from Raiskin's class discuss what they've found in the archives.

Beth Peters, a general science major and biology minor, talked about how she connected to the class after growing up in The Dalles, Oregon where the Rajneesh poisoned 751 people with salmonella in 1984. She saw Touching Artifacts as an opportunity to engage with her hometown’s history and look at how her neighbors’ lives were affected — especially in light of the release of Wild, Wild Country, a Netflix documentary about the Rajneeshpuram.

“This is a really interesting collision: a historical study as well as a social study through a general science major,” said Peters.

She conducted interviews with a person who was poisoned, someone working for the lab at the hospital and the director of the county planning office — someone who turned out to actually be her next door neighbor — while also using SCUA manuscripts.

“One thing that I realized working in the collections is the different perspectives that people will have on the same thing,” said Peters. “One event can mean something different to different people even though they’re all still involved.”